Newt Gingrich claims that “more people have been put on food stamps by Barack Obama than any president in American history.” He’s wrong. More were added under Bush than under Obama, according to the most recent figures.

The former speaker made that claim Jan. 16 in a Republican debate in Myrtle Beach, S.C., and his campaign organization quickly inserted the snippet in a new 30-second TV ad that began running Jan. 18 in South Carolina.

Gingrich would have been correct to say the number now on food aid is historically high. The number stood at 46,224,722 persons as of October, the most recent month on record. And it’s also true that the number has risen sharply since Obama took office.

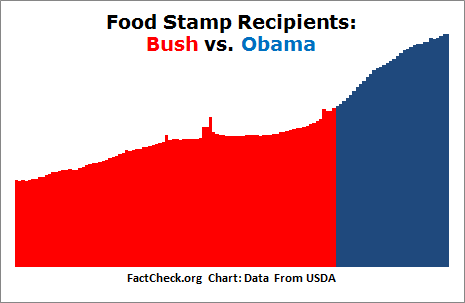

But Gingrich goes too far to say Obama has put more on the rolls than other presidents. We asked the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition service for month-by-month figures going back to January 2001. And they show that under President George W. Bush the number of recipients rose by nearly 14.7 million. Nothing before comes close to that.

And under Obama, the increase so far has been 14.2 million. To be exact, the program has so far grown by 444,574 fewer recipients during Obama’s time in office than during Bush’s.

It’s possible that when the figures for January 2012 are available they will show that the gain under Obama has matched or exceeded the gain under Bush. But not if the short-term trend continues. The number getting food stamps declined by 43,528 in October. And the economy has improved since then.

Update, Feb. 5: Revised USDA data released in February showed the downward trend continued for a second straight month in November, when the number of persons getting food stamps was 134,418 fewer than it had been at the peak.

Obama’s Responsibility

Gingrich often cites the number of persons on food stamps to support his view that the U.S. is becoming an “entitlement society,” increasingly dependent on government aid. And he has a point. One out of seven Americans is currently getting food stamps.

But Gingrich strains the facts when he accuses Obama of being responsible. The rise started long before Obama took office, and accelerated as the nation was plunging into the worst economic recession since the Great Depression.

The economic downturn began in December 2007. In the 12 months before Obama was sworn in, 4.4 million were added to the rolls, triple the 1.4 million added in 2007.

To be sure, Obama is responsible for some portion of the increase since then. The stimulus bill he signed in 2009 increased benefit levels, making the program more attractive. A family of four saw an increase of $80 per month, for example. That increase remains in effect and is not set to expire until late next year, according to USDA spokeswoman Jean Daniel.

The stimulus also made more people eligible. Able-bodied jobless adults without dependents could get benefits for longer than three months. That special easing of eligibility also expired on Sept. 30, 2010. Spokeswoman Daniel told us that 46 states have been able to continue the longer benefit period under special waivers granted because of high unemployment. Previously, able-bodied adults without dependents could collect food stamps for only three months out of any three-year period.

Otherwise, current eligibility standards are unchanged from what they were before Obama took office, USDA officials say. Generally, those with incomes at or below 130 percent of the official poverty level, and savings of $2,000 or less, may receive aid. The income level is currently just over $29,000 a year for a family of four.

That leaves the economic downturn that began in 2007 — and the agonizingly slow recovery that followed — as the principal factors making more Americans eligible for food stamps. Officials say that another factor is that Americans today are less reluctant to accept aid than before.

Of those whose income was low enough to qualify, only 54 percent actually signed up in 2002, but that rose steadily to 72 percent by fiscal 2009, the latest USDA figures show (See Table 2).

USDA researchers said the jump in the participation rate happened because of actions by state governments. In a report released in August 2011, the Office of Research and Analysis said:

USDA: States have increased outreach to low-income households, implemented program simplifications, and streamlined application processes to make it easier for eligible individuals to apply for and receive SNAP [food stamp] benefits. Most States also have reduced the amount of information that recipients must report during their certification period to maintain their eligibility and benefit levels, making it easier for low-income households to participate.

Another reason may be that “food stamps” no longer exist as paper coupons. Instead, beneficiaries now receive plastic debit cards, known as “Electronic Benefit Transfer” or EBT cards, which look pretty much like an ordinary credit card when used in a supermarket checkout line.

Another reason may be that “food stamps” no longer exist as paper coupons. Instead, beneficiaries now receive plastic debit cards, known as “Electronic Benefit Transfer” or EBT cards, which look pretty much like an ordinary credit card when used in a supermarket checkout line.

EBT cards have been used in all states since 2004, according to the USDA website. The change to plastic cards was done both to reduce the possibility of fraud, and also to reduce the stigma felt by beneficiaries, and may account for some of the increase in participation.

In fact, the program is no longer officially called the “food stamp” program. Since 2008, it has been the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP for short.

Who Gets Food Stamps?

The most recent Department of Agriculture report on the general characteristics of the SNAP program’s beneficiaries says that in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, 2010:

- 47 percent of beneficiaries were children under age 18.

- 8 percent were age 60 or older.

- 41 percent lived in a household with earnings from a job — the so-called “working poor.”

- The average household received a monthly benefit of $287.

- 36 percent were white (non-Hispanic), 22 percent were African American (non-Hispanic) and 10 percent were Hispanic (Table A.21).

Update, Feb. 5: USDA data understate these figures, however, because participants are not required to state their race or ethnic background. As a result, 18.9 percent are listed as “race unknown.”) A more accurate estimate of the racial and ethnic composition of food-stamp recipients can be drawn from U.S. Census data, based on a sample of households surveyed each year in the American Community Survey. For 2010, Census data show the following for households that reported getting food stamp assistance during the year:

- 49 percent were white (non-Hispanic); 26 percent were black or African American; and 20 percent were Hispanic (of any race).

Note that Census data somewhat understate the total number of persons receiving food stamps, compared with the more accurate head count from USDA, which is based on actual benefit payments. Survey participants may be reluctant to state that they have received public assistance during the year. So the Census figures on race and ethnic background can’t be guaranteed to be completely accurate. But we judge the Census figures to be a better approximation of reality regarding race and ethnic background than USDA figures.

We don’t argue that the program is either too large (as Gingrich does) or too small. It has certainly reached a historically high level, and may or may not grow even larger in the months to come. But the plain fact is that the growth started long before Obama took office, and participation grew more under Bush.

Kevin Concannon, the USDA’s undersecretary for food, nutrition and consumer services, told the Wall Street Journal: “I realize Mr. Gingrich is a historian, but I’m not sure he’d get very high marks on that paper.”

— Brooks Jackson

Footnote: There was an earlier easing of eligibility standards buried in a 2008 farm bill that Congress enacted over Bush’s veto. Obama voiced support for the measure while campaigning, but was not present for either the Senate vote to pass the bill or the vote to override.

Both votes enjoyed strong bipartisan majorities. Only 12 Republicans and two Democrats voted to sustain Bush’s veto, for example. Bush didn’t mention the food stamp provisions when he vetoed the bill, but instead cited what he called excessive subsidies to farmers.