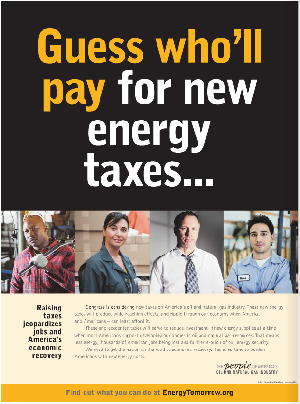

It didn’t take long after President Obama released his latest budget for the oil lobby to pick up the misleading cry that it’s being targeted for “new taxes.” That’s mostly not true. Energy Tomorrow, a project of the American Petroleum Institute, ran a print ad in Washington, D.C.’s Politico Feb. 14 asking, “Guess who’ll pay for new energy taxes?”

The problem with that rhetorical question is that most of the “new taxes” are actually a proposed end to some old tax breaks — advantages not shared by other industries.

The problem with that rhetorical question is that most of the “new taxes” are actually a proposed end to some old tax breaks — advantages not shared by other industries.

The ad comes only days after we criticized the wind-power lobby for making a similar claim, trying to pass off the scheduled expiration of a special tax credit for wind-generated electricity as “new taxes” on that industry. (See “Wind Spin,” Feb. 9.) So now we apply the same standard to the fossil fuel crowd.

It’s true that the president proposes raising $38.7 billion in additional taxes from the oil and gas industry over the next 10 years. But his budget would do so by repealing several existing preferences now enjoyed by the industry, not by imposing “new taxes.”

Special Oil & Gas Breaks

For example, the budget proposes (page 6) to raise nearly $14 billion over the next 10 years by repealing the industry’s ability to write off most or all of its “intangible” drilling expenses (including labor costs and rig time) immediately. Instead, the expenses would be deducted over seven years.

The budget also would repeal the industry’s “depletion allowance,” which allows royalty owners and independent producers to avoid taxes on 15 percent of their income from producing oil and gas wells. That would raise an estimated $11.5 billion over 10 years.

The budget also would repeal the industry’s “depletion allowance,” which allows royalty owners and independent producers to avoid taxes on 15 percent of their income from producing oil and gas wells. That would raise an estimated $11.5 billion over 10 years.

Further, the budget proposes to raise $1.4 billion over the next 10 years from smaller exploration firms by repealing the special treatment of their costs of exploration. Currently, independent drillers and smaller integrated oil and gas companies can write off their geological and geophysical expenditures over only two years, while major integrated companies must spread their deductions over seven years. Obama would make that seven years for all firms.

Those three measures are all listed by the U.S. Congress’ nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation as “tax expenditures,” another way of saying subsidies or special breaks given to the industry.

And One New Tax

But in at least one instance, Obama proposes to treat the oil and gas industry less favorably than other industries, giving them a good case to argue that a “new” tax would result. The president proposes again (as he did in 2011) to repeal the “domestic manufacturing deduction” — but only for the oil, gas and coal industries.

That would raise an estimated $11.6 billion over the decade from the oil and gas industries (and another $271 million from coal miners). That credit, passed in 2004, allows companies that manufacture in the U.S. to deduct 9 percent of their income attributable to domestic production.

The aim of the credit is to keep U.S. companies from moving manufacturing production overseas. The argument for repealing it for oil, gas and coal is that domestic wells and mines can’t be moved, making the credit a windfall for oil and gas. But the credit isn’t specific to oil and gas (or coal), so we judge that denying it only to those industries amounts to a “new” tax on them (just as denying, say, the mortgage interest deduction on homes in Cleveland or Los Angeles would amount to a new tax on homeowners in those places).

We of course take no position either way on whether Obama’s oil and gas proposals should be enacted or rejected. Our point here is that a favored industry is seeking to hold onto existing, special tax breaks while claiming to be a target of “new” taxes.

— Brooks Jackson