Sen. Bernie Sanders frequently says corporate income tax receipts have dropped from more than 30 percent of federal revenue in the 1950s to only 11 percent in 2015, leaving the impression that favorable tax policies are the reason. But there are several factors behind that drop.

Since 1953, there has been a rise in payroll taxes — spurred in part by the creation of Medicare — and in recent decades a shift from corporate taxes to pass-through business taxes paid individually by owners, as well as legislative changes to corporate taxation.

On Sanders’ campaign website, on a page about “Making the Wealthy, Wall Street, and Large Corporations Pay their Fair Share,” the Democratic presidential candidate says: “In 1953, the corporate income tax accounted for 32 percent of all federal revenue. Today, despite record-breaking profits, corporate income taxes only bring in 11 percent of total federal revenue.”

On Feb. 11, he tweeted: “In the 1950s large corporations contributed over 30% of federal tax revenue. Today it’s less than 10 and they still ask for more tax breaks.”

Sanders’ claims leave the false impression that corporations’ tax receipts would still amount to about a third of federal revenues if they only weren’t able to take advantage of tax breaks and other favorable taxation policies. But the decline in corporate tax receipts over the past six decades is more complicated than that and can’t be attributed solely to tax avoidance.

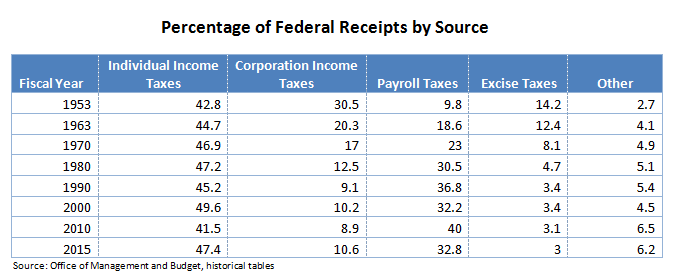

Corporate tax receipts haven’t been as high as 30.5 percent of federal tax revenues since 1953. They dropped to 20.3 percent by 1963, and by 1980, they were down to 12.5 percent. (See Table 2.2 on tax receipts from the Office of Management and Budget.) So the decrease happened much faster than Sanders’ statistic indicates.

At the same time, payroll taxes represented a growing percentage of federal tax receipts. In 1953, Medicare didn’t exist yet — it was enacted in 1965. And the payroll tax rates and income thresholds for Social Security and Medicare have gone up over the years. In 1953, payroll taxes were 9.8 percent of federal receipts; a decade later, they were 18.6 percent, and by 1980, they hit 30.5 percent. In 2015, they were 32.8 percent of federal receipts.

Individual income taxes, meanwhile, have been above 40 percent for several decades. Here’s a breakdown of federal tax receipts by source over the years since 1953:

The magnitude of the decrease Sanders cites was evident more than 30 years ago, in 1980, and corporate receipts have continued to be around 10 percent ever since. What happened to corporate taxes from 1953 to 1980?

Corporate taxation changed, as did corporate profits. A 1987 paper by Alan J. Auerbach, then with the National Bureau of Economic Research, and James M. Poterba, with MIT’s economics department, titled “Why Have Corporate Tax Revenues Declined?,” looked at that drop over the previous 25 years, from 1959 to 1985. The authors found that the decline in corporate profits was a bigger factor than legislative changes: “[W]hile legislative changes have been important contributors to the decline of corporate tax revenues, they account for less than half of the change since the mid-1960s. Reduced profitability, which has shrunk the corporate tax base, is the single most important cause of declining corporate taxes,” Auerbach and Poterba wrote.

Eric Toder, codirector of the Tax Policy Center, told us that the change in the percentage of corporate receipts from 1950 to the early 1980s was “maybe half tax policy changes and half economic changes.”

In the 1950s through 1963, the top corporate tax rate was 52 percent. In the early 1980s, it was 46 percent (and fell further to 35 percent today). Other factors included accelerated depreciation, investment credits and U.S. companies investing overseas. But corporate debt also went up over that time period, Toder said, so there were reduced profits.

And of course, the percentage of federal receipts in payroll taxes went up significantly. A tripling of the percentage of payroll taxes makes the percentage of other receipts look smaller.

Since the 1980s, the percentage of corporate tax receipts hasn’t grown, partly due to a shift from businesses paying corporate taxes to more and more businesses being organized as pass-through entities, in which profits are passed through to the owners or members, who pay taxes on that profit through their individual income tax returns.

The Shift to Pass-Through Businesses

When Sanders compares 1953 corporate taxes to today, he’s leaving out information about how businesses paid taxes back in 1953 and how they pay taxes now. A greater percentage are now taxed at the individual level through owners, a trend that has occurred largely since the early 1980s.

Sole proprietorships and other unincorporated businesses have paid taxes at the individual level since the individual income tax was created in 1913, according to a 2012 report on pass-through business income by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. But in 1958, S corporations were created, enabling businesses to have liability protection and pass profits through to their owners. There were certain requirements for businesses to meet to qualify for S corporation status, such as a limit on the number of shareholders, and in the 1980s, the requirements were loosened. This “pass-through” structure is how partnerships and LLCs, which came about largely in the 1990s, are also organized.

From 1980 to 2007, CBO said, the percentage of businesses that were C corporations went from 17 percent to 6 percent. “That change was more than offset,” CBO said, “by the increase in the hybrid forms described earlier — specifically, limited partnerships, S corporations, and LLCs; that set of entities increased from 5 percent to 20 percent of all businesses” during that period. (Sole proprietorships, the most popular form of business, “remained fairly steady” at 70 percent to 75 percent.)

While C corporations made up only 6 percent of businesses in 2007, they still were responsible for most of U.S. business receipts. (C corporations — like publicly traded companies — tend to be larger entities.) But, the percentage of business receipts attributable to C corporations declined from 86 percent in 1980 to 62 percent in 2007, the CBO report said.

And that figure has slipped even further since.

An October 2015 paper by several experts with the Treasury Department and National Bureau of Economic Research — titled “Business in the United States: Who Owns it and How Much Tax Do They Pay?” — examined this shift in business receipts, finding that C corporations “now account for less than half of business income.”

In 2011, pass-through entities earned the majority of business income — 54.2 percent, that paper found.

Toder, at the Tax Policy Center, cited a few reasons for this change — the rules for S corporations were loosened in the 1980s, and in 1986, the top individual tax rate became lower than the corporate rate, giving businesses incentive to become pass-through entities. CBO also points to the change in the economy from the production of goods to more service-providing industries.

The pro-business Tax Foundation also has chronicled the decline in C corporations, writing in January 2015 that there were 1.6 million C corporations in 2011, according to IRS data, “the lowest number of traditional corporations since 1974 and 1 million fewer than there were at the peak in 1986.” The Tax Foundation says the “main driver of this trend is the country’s poorly structured tax code, specifically its two layers of tax on C corporations,” which pay taxes on corporate income and then their shareholders pay dividend and capital gains taxes on profits that are distributed to them. With pass-throughs, there’s only the individual income taxes paid on profits, whether those profits are distributed to owners/members or not.

The Tax Foundation report, by William McBride, says this trend is troubling for the economy, as C corporations “usually provide the most efficient business structure for large-scale projects and investments.” (The Tax Foundation’s solution is the opposite of Sanders’ — lower corporate taxes and treat “all businesses alike.”)

The growth in pass-throughs since 1980, Toder noted, means that the big drop in the percentage of corporate tax receipts from 1953 through the early 1980s can’t be attributed to this phenomenon. But “it is a reason perhaps corporate receipts haven’t grown … because receipts have gone into S corporations and limited partnerships. … That has raised individual income tax receipts.”

The October 2015 paper estimated the average income tax rates for various types of businesses, finding that the C-corporation sector paid the highest average rates in 2011, at 31.6 percent. The S-corporation sector had an average rate of 24.9 percent; partnership had a rate of 15.9 percent and sole proprietorships were at 13.6 percent. If instead that 2011 business income had been earned as such income was in 1980 (with fewer pass-throughs), that business income would have led to an additional $100 billion in taxes, the paper found.

And, of course, much more of the business tax revenue overall would show up under the corporate income tax receipts.

“It is highly likely corporate revenues would be higher if pass-throughs hadn’t happened,” Owen Zidar, one of the authors of that paper and an assistant professor of economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, told us in an email.

In fact, Zidar and his coauthors found that the shift to pass-throughs was responsible for “much of the rise in income inequality over the last three decades,” as this type of business income is more likely to flow to the top 1 percent.

The 2012 paper from CBO also determined that business tax receipts would be higher if not for movement to pass-through entities. In 2007, when pass-throughs accounted for 38 percent of business receipts, there would have been an additional $76 million in tax revenues if “S corporations and LLCs had been taxed as C corporations in 2007.” That estimate takes into consideration the tax impact on corporate, individual and payroll taxes.

Both of these estimates on increased tax receipts note that they don’t account for how businesses might change their behavior if they were taxed differently.

All of this is to say that there are several factors that have contributed to the decline in corporate tax receipts. Experts we spoke with also cited as having some impact issues of tax avoidance and keeping money overseas where tax rates are lower — one of Sanders’ main targets in his proposals to change the corporate tax laws.

But it’s unclear what exactly that impact is.

“There’s no doubt that multinational corporations … represent a bigger share of corporate income now than they did” in the past, said Alan J. Auerbach, author of the 1987 paper we cite above and now director of the Robert D. Burch Center for Tax Policy and Public Finance at the University of California, Berkeley. “That is a serious tax policy issue. … But we don’t know to what extent that is eroding the corporate tax base.”

Auerbach told us in a phone interview that “that’s not the big story” in recent decades. Instead, the big story is that other sources of revenue, namely payroll taxes, have been growing and C corporations have been declining as a share of the business sector.

In its most recent report on the budget and economic outlook, the CBO says corporate receipts in 2014 were “1.9 percent of GDP—near the 50-year average.” It expected that percentage to grow in the next few years and then decline to 1.8 percent of GDP in 2025 “largely because profits are projected to decline relative to GDP,” a decrease CBO attributes “primarily” to increased labor costs and interest payments on business debt.

It cites three other factors for that projection: the expiration of rules on equipment investment deductions, a continued shift to pass-through entities rather than C corporations, and the use of strategies to shift corporate income out of the United States. “By 2025, in CBO’s baseline, corporate income tax receipts are roughly 5 percent lower than they would be without that further erosion of the corporate tax base; slightly more than half of that difference is attributable to the shifting of additional income out of the United States,” CBO said.

Sanders’ figures are largely correct — the share of federal revenues from corporate taxes did decline from 30.5 percent (he said 32 percent) in 1953 to nearly 11 percent in 2015 — and there’s support for his implication that shifting income overseas has played some role. But there’s a lot more to the story than that. The drop in corporate tax receipts over 60-plus years is also attributable to a decline in corporate profits in earlier decades, a large increase in payroll taxes, and the growth in businesses being organized as pass-through entities, which pay taxes on the individual level.