The chairman of the Senate environment committee falsely claimed that a new report “confirms” that “hydraulic fracturing has not impacted drinking water” in Wyoming. The report said a lack of water quality data predating oil and gas exploration prevented it from reaching “firm conclusions.”

Sen. James Inhofe, who chairs the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, made his remarks in a statement issued Nov. 10 — the day that the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality issued a report on water-supply wells in Pavillion, a small town southeast of Yellowstone National Park.

The industry-funded state report specifically looked at the “likelihood of impacts from oil and gas operations” on 14 water-supply wells used by residents living near Pavillion. Since the 1990s, residents in the area have “complained of physical ailments and said their drinking water was black and tasted of chemicals,” ProPublica reported.

Inhofe, Nov. 10: The Wyoming DEQ’s thorough investigation over the past several years has come to a close and confirms what we’ve known all along: hydraulic fracturing has not impacted drinking water resources.

But that’s not what the report said.

The “fact sheet” for the Wyoming report said it’s “unlikely” that hydraulic fracturing had “any impacts” on these water-supply wells, but “[l]imited baseline water quality data, predating development of the Pavillion Gas Field hinders reaching firm conclusions on causes and effects of reported water quality changes.”

In the next sections, we’ll examine why it’s difficult to isolate fracking from other potential causes of water contamination, and why the Wyoming report didn’t reach “firm conclusions.” We’ll also review the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s research to date on fracking practices that take place across the country, and Inhofe’s unsupported claim that it is “abundantly clear” that fracking does not impact drinking water.

Muddied Causes

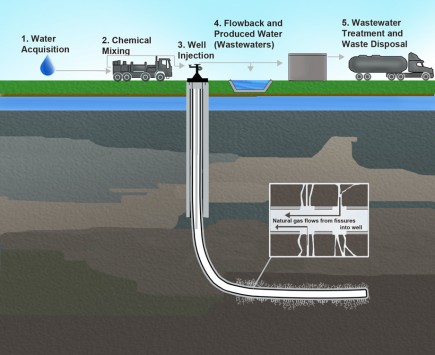

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a technique often used to retrieve natural gas and oil often from shale, a rock layer deep below the earth’s surface. The process entails injecting water, sand and chemicals at high pressure, releasing oil and gas that would otherwise be difficult to recover.

About half of U.S. crude oil production and two-thirds of natural gas production now involve fracking — a significant share of production that has steadily increased over the last 15 years, according to the Energy Information Administration.

With this boom have come concerns about the impact of oil and gas drilling on water quality, as we wrote in March 2015 when we checked another false fracking claim made by Inhofe.

With this boom have come concerns about the impact of oil and gas drilling on water quality, as we wrote in March 2015 when we checked another false fracking claim made by Inhofe.

Much of the debate surrounding whether fracking has led to groundwater contamination in Wyoming and elsewhere stems from a lack of water quality data predating fracking and oil and gas production in general.

Without this information, researchers are less equipped to assess the relative impact of three possible sources on water quality: naturally occurring phenomena, conventional oil and gas recovery methods, and unconventional methods, including fracking.

Since 1960, for example, both conventional and unconventional methods have been used to extract fuel from the Pavillion gas field. If water quality data had been collected before the drilling started, and since then, scientists could have compared that data with trends in the use of specific practices over the years.

Conventional methods typically include drilling vertically to recover more easily accessible fuel from relatively shallow, permeable rock. Fracking and horizontal drilling, often used in unison, fall under unconventional methods.

As its name suggests, horizontal drilling often involves drilling deeper to less porous shale rock and then drilling horizontally. (See the adjacent image.) This enables a single well to cross through a greater portion of a fuel reservoir and, as a result, recover more fuel.

As its name suggests, horizontal drilling often involves drilling deeper to less porous shale rock and then drilling horizontally. (See the adjacent image.) This enables a single well to cross through a greater portion of a fuel reservoir and, as a result, recover more fuel.

But fracking doesn’t necessarily have to occur deep below the earth’s surface or in horizontal wells. In fact, fracking was used in some relatively shallow Pavillion field wells, which means the activities took place closer to the aquifer tapped by residents’ water-supply wells. All of the 169 wells in the field are also vertically-drilled wells, according to the EPA.

Both conventional and unconventional fuel recovery methods have the potential to negatively impact groundwater resources, as do naturally occurring processes, such as bacteria proliferation or the natural movement of methane underground.

So how could the boom in oil and gas production from fracking lead to water contamination?

Among other mechanisms, methane, the main component of natural gas, could leach into aquifers through improperly constructed drilling wells or through cracks underground produced during the fracturing process. However, methane can naturally migrate into aquifers without the help of fracking, blurring the line between natural and anthropogenic, or human-caused, sources.

Salty fracking fluids, which can contain toxic chemicals, also could leach into the aquifer after they’re disposed of improperly or spilled. Lastly, fracking can influence the underground ecosystem’s biology, further blurring the line between natural and anthropogenic causes.

For example, bacteria are known to interact with the fracking process. In fact, a species of bacteria — the so-called “Frackibacter” — has specifically evolved to live in the subterranean environment shaped by fracking.

Generally, bacteria have “both positive and negative impacts on energy recovery,” the Ohio State University researchers who discovered the new bacteria wrote in their paper published in Nature Microbiology in September.

For one, some bacteria play an important part in producing natural gas in the first place. But during the recovery of the fuel, bacteria can “sour” the fuel by producing sulfide, a toxic chemical that smells like rotten eggs. Bacteria can also contribute “to corrosion [of the drilling well] and the risk of environmental contamination,” the researchers wrote.

To kill these bacteria, “biocides like formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde are thrown down the [wells] in an attempt to preserve a usable [fuel] product,” reported Wired. These chemicals could then leach into aquifers in the routes described above. After wells are abandoned, these bacteria can also “come back with a vengeance, generating acidic byproducts that can corrode pipes and release heavy metals,” Wired wrote.

There are ways to distinguish natural from anthropogenic causes, such as using isotopic analysis, which aims to distinguish the signatures of different sources of compounds, but the technique isn’t always sensitive enough to detect the difference. Overall, given the lack of baseline data, it’s often difficult to “confirm” that fracking in particular has played a role in water contamination.

State and Federal Fracking Fray

The Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality announced that it would undertake the water-quality study in June 2013 — about 18 months after the EPA released a draft report that found chemicals associated with fracking in the groundwater near Pavillion.

The EPA decided to turn the investigation over to the state after its report was criticized by state officials, Congress and industry representatives, according to a Dec. 6, 2015, report by the Casper Star-Tribune. The Wyoming newspaper obtained about 56,000 EPA documents in a Freedom of Information Act request that the paper said revealed “an EPA worried it could not defend its Pavillion study against an onslaught of criticism.”

In announcing the state would “further investigate” the water quality in Pavillion, the EPA said it “stands behind its work and data,” but “does not plan to finalize or seek peer review of its draft Pavillion groundwater report released in December, 2011.”

The Wyoming state study was headed by a private company, Acton Mickelson Environmental Inc., and was funded by Encana, the company that owns Encana Oil and Gas (USA) Inc., which operates the Pavillion gas field.

We emailed Kevin Frederick, water quality administrator at the Wyoming Department of Environmental Quality, to ask what role state scientists played in the report. He told us they “observed sample collection, evaluated sample results, and participated in development of the draft and final reports” while working with Acton Mickelson Environmental Inc.

As we previously noted, the fact sheet for the Wyoming report concluded it’s “unlikely” that fracking had “any impacts” on these water-supply wells. However, it added, “Limited baseline water quality data, predating development of the Pavillion Gas Field hinders reaching firm conclusions on causes and effects of reported water quality changes.”

Instead, the state report said bacteria “may be a cause of taste and odor issues” with the well water.

But in its comments on a draft of the report, the EPA argued that the state didn’t support many of its conclusions with enough data. The EPA said “data limitations and uncertainties … suggest a need for additional investigation to provide support for many of the Report’s conclusions.”

For example, the Wyoming state report found, “Exceedances of drinking water standards or comparison values” found in the water-supply wells are “generally limited to naturally occurring dissolved salts, metals, and radionuclides.”

In its comments on the draft report, the EPA wrote that “there is limited supporting evidence demonstrating that all of these constituents were present historically in the area, and that they were present at similar concentrations to those detected,” i.e., that they were naturally occurring.

High levels of sodium and sulfate are “characteristic” for the region, the EPA added. But “there is limited or no historic data in the references cited in the Report to document naturally occurring levels of many other inorganic constituents such as arsenic, thallium, lithium and uranium, and the limited data suggest that the values seen in water wells are not consistent with background concentrations,” the EPA said.

In its response to the EPA’s comments, Wyoming officials said that their report “states that those constituents that exceed drinking water standards … are naturally occurring dissolved salts, metals and radionuclides, not that the exceedances are naturally occurring,” a point that was not clarified in the state’s final report.

“Due to the absence of baseline water quality data from the study wells, there is insufficient evidence to determine if the reported exceedances do, or do not represent natural aquifer concentrations,” the state added in its response to the EPA.

The EPA also commented on the state’s conclusion that bacteria may be to blame for residents’ complaints about the poor taste and odor of the drinking water. The EPA agreed that the report showed a “correlation” between “dissolved organic compounds,” such as methane, in the water and the “proliferation of bacteria.” But it argued that this correlation doesn’t “establish … the source.”

In other words, fracking and related practices could be indirectly to blame for water quality issues.

In its final version, the Wyoming report did state that gas in the water could be from anthropogenic and/or natural sources.

The state report also concluded that it’s unlikely that fracking fluids have interacted with “shallow groundwater supplying the study wells,” in part, because of the depth at which the fracking occurs underground. The water-supply wells reach 30 feet to 675 feet below the surface, while the “shallowest” fracking occurs “generally deeper than 1,500 ft,” the state said.

But the EPA in its comments on the draft report countered that the fracking of some of the drilling wells “occurred at a substantially shallower depth.”

Also, Dominic DiGiulio and Robert Jackson, earth and environmental scientists at Stanford University, published a paper in March in the journal Environmental Science and Technology that linked shallow fracking to toxic chemicals in aquifers in Pavillion.

For example, “Acid stimulation and hydraulic fracturing occurred as shallowly as” 699 feet and 1,056 feet below the surface, respectively, “at depths comparable to deepest domestic groundwater use in the area,” the authors wrote. Like hydraulic fracturing, acid stimulation (e.g. hydrofluoric acid and hydrochloric acid) is used to improve oil and gas recovery.

In an interview with WyoFile, a local Wyoming news outlet, DiGiulio, who was an EPA scientist for over 25 years and co-authored the agency’s 2011 draft report on Pavillion, said his 2016 study with Jackson stops “short of saying that there’s strong evidence tying” fracking to impacts on the water wells. But their paper had found that fracking has impacted the groundwater, which is water that may be used in the future.

In other words, DiGiulio and Jackson looked at groundwater generally, while the state looked at specific wells — an important distinction.

In an email DiGiulio and Jackson told us the state needs to install monitoring wells, solely used for research purposes, in the area to delineate the extent of groundwater contamination and to “better address risk posed to domestic water wells.”

The EPA did install two monitoring wells in the Pavillion field and used data collected from them in its 2011 report. However, the state didn’t use this data for its report because some expressed “concerns” about the construction and sampling of the two wells during the public comment period for the EPA report.

DiGiulio and Jackson also told us that about 20 additional water wells, out of 121 wells total, should be tested due to their proximity to unlined pits, where fracking fluids and other toxic byproducts of oil and gas exploration were disposed.

DiGiulio and Jackson told us that “there can be a lag period of decades before contaminants” in groundwater reach a water well. “These contaminants present a long-term unaddressed risk to domestic water wells” if the contaminants continue to move upwards toward water wells, they added.

Regardless of the criticisms of both state and federal investigations, even if the conclusions made in the Wyoming report are taken at face value, they still don’t “confirm” that “hydraulic fracturing has not impacted drinking water resources” near Pavillion, as Inhofe claimed.

Pavillion: National Implications

Inhofe draws national implications from the Pavillion study, claiming it adds to growing body of scientific research that proves fracking does not contaminate groundwater.

“Ultimately, the facts have prevailed and the record is abundantly clear, with even the EPA affirming that ‘hydraulic fracturing activities have not led to widespread, systemic impacts to drinking water resources’ in its landmark water study,” Inhofe said in his Nov. 10 statement.

It is not, however, “abundantly clear” that fracking does not impact drinking water and there is evidence to suggest otherwise.

Inhofe is referring to a June 2015 draft report in which the EPA said it “did not find evidence” that hydraulic fracturing has “led to widespread, systemic impacts to drinking water resources in the United States.” But the EPA’s draft report has been challenged by its own advisory board and a final report has yet to be issued.

The EPA’s Science Advisory Board wrote a letter dated Aug. 11 to EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy, stating that the EPA failed to “quantitatively” support its conclusion that fracking has “not led to widespread, systemic impacts to drinking water resources.” The board also said the EPA didn’t “clearly describe” whether the conclusion pertained to groundwater and/or surface water nor what exactly it meant by the terms “systemic” and “widespread.”

If the EPA wanted to retain its conclusion in its final report, the agency should address these issues, the advisory board said.

On Nov. 21, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy said the agency is “trying to wrap [the final report] up soon,” but she didn’t specify a date. “We’re certainly going to listen to the direction of the science advisory board,” but the “challenge for us is to characterize what we know” without over-generalizing limited data, she added.

Inhofe has cited the draft EPA report in the past to support his position that fracking has no impact on drinking water. He claimed last year that the EPA draft report “confirms” that fracking is “safe.” As we said at the time, the EPA reported specific cases of water contamination related to fracking and made no determination of safety.

Similarly, Inhofe draws sweeping conclusions from the Wyoming state study that are not supported by the research.

As we already explained, the state report did not reach “firm conclusions on causes and effects of reported water quality changes” in specific wells, while the DiGiulio and Jackson study of Pavillion did find evidence that linked shallow fracking to toxic chemicals in the area’s groundwater.

Researchers know that shallow fracking and poor well integrity, which occurred in Pavillion, can raise the likelihood of water contamination. So how common are these practices?

An estimated 16 percent of fracked wells in the country are less than a mile deep (i.e. shallow), according to a separate survey published by Jackson, DiGiulio and others in Environmental Science and Technology in July 2015. Most of those shallow wells are located in Texas and California.

But the researchers believe that their estimate is low. They predominately looked at wells drilled in the U.S. between 2010 and 2013. At the beginning of 2012, only a few states — Colorado, Louisiana, Montana, North Dakota, and Texas — mandated companies to report well data to FracFocus, the database the researchers used to conduct their analysis. For other states, reporting is voluntary.

The researchers also looked at state regulations governing fracking well construction and groundwater protection and found that they varied widely.

For example, some states, such as New Mexico and Utah, do not have to have minimum surface casing depths. Surface casings are pipes within the wells that aim to prevent water contamination. If they don’t extend beyond the groundwater level, there’s a higher chance of contamination.

In Wyoming, however, surface casings must reach deeper than “all known usable groundwater,” the researchers explained. And in Texas, drilling wells that have “less than 1,000 feet of vertical separation” from groundwater require additional testing for integrity.

DiGiulio and Jackson conclude their paper by suggesting that operators should provide more information about their wells in the form of a “mandatory state or federal registry,” which “would allow people to track the locations, depths, and volumes of chemicals used around them.”

In addition, the researchers argue that state or federal governments should require “full chemical disclosure — without trade secret exemptions — for all chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing above 3000 ft.” While most states do require disclosure of some chemicals, oil and gas operators don’t have to report them all because of trade secrets laws, which also protect Coca-Cola’s recipe, for example.

While Inhofe says it is “abundantly clear” that fracking has no impact on drinking water resources, the fact is that researchers do not have the data to make such a sweeping and firm conclusion – specifically in Pavillion and more generally in the U.S. at large.

Editor’s Note: SciCheck is made possible by a grant from the Stanton Foundation.

https://www.sharethefacts.co/share/3bc30cf3-3cd8-4a5f-a183-403cf631166a