In an address to law enforcement, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions made two dubious claims about marijuana and opioids:

- Sessions said marijuana is “only slightly less awful” than heroin, an illicit opioid. Experts says heroin is three times more harmful than marijuana based on a rating scale that takes into account lethal overdoses, dependence potential, economic harm and other factors.

- He said he is “astonished to hear people suggest that we can solve our heroin crisis by legalizing marijuana.” While medical marijuana may not “solve” the epidemic, research suggests legalization may curb opioid overdoses, which have surged in recent years.

Sessions made his claims on March 15 during an address to law enforcement at the Justice Department. He first discussed trends in violent crime, correctly noting that while “crime rates in our country remain near historic lows,” FBI statistics show that “the violent crime rate in the U.S. increased by more than 3 percent” between 2014 and 2015.

Sessions also said that it’s his “fear” that the increase in violent crime is “the start of a dangerous new trend.” Later on during his speech, he added that to “turn back this rising tide of violent crime, we need to confront the heroin and opioid crisis in our nation.”

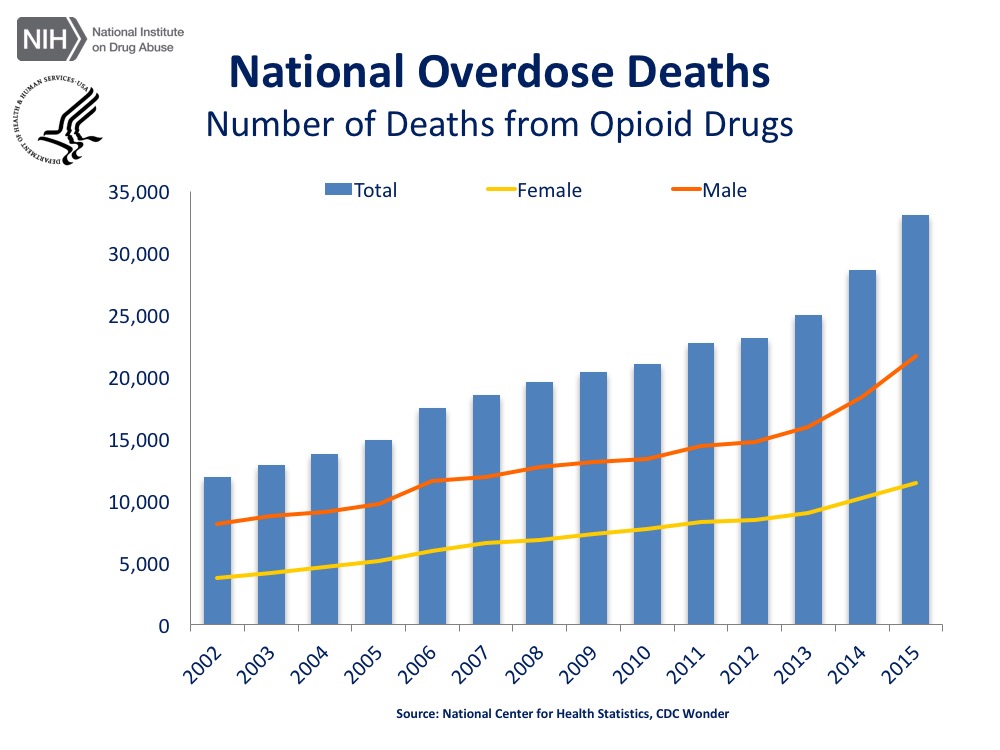

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 52,404 people died of drug overdoses in 2015, 63.1 percent of which involved an opioid. This includes illicit opioids, such as heroin, and prescription opioids, including oxycodone and hydrocodone.

The 2015 numbers are part of a larger trend. Opioid-related deaths have gone from around 3 per 100,000 people in 2000 to over 10 per 100,000 people in 2015, according to the CDC.

At the same time that opioid-related deaths have increased, the CDC also notes, “Sales of prescription opioids in the U.S. nearly quadrupled from 1999 to 2014, but there has not been an overall change in the amount of pain Americans report.”

So Sessions was on the mark when he said that “every three weeks, we are losing as many American lives to drug overdoses as we lost in the 9/11 attacks.” About 3,023 people die every three weeks of drug overdoses, while 2,977 died in the 9/11 attacks. But he made other claims about drugs that were questionable:

Sessions, March 15: I reject the idea that America will be a better place if marijuana is sold in every corner store. And I am astonished to hear people suggest that we can solve our heroin crisis by legalizing marijuana – so people can trade one life-wrecking dependency for another that’s only slightly less awful. Our nation needs to say clearly once again that using drugs will destroy your life. In the ’80s and ’90s, we saw how campaigns stressing prevention brought down drug use and addiction. We can do this again.

We’ll explain why Sessions’ claim that marijuana is “only slightly less awful” than heroin contradicts expert opinion. We’ll also lay out evidence that suggests medical marijuana may help curb the opioid epidemic, which includes heroin.

Marijuana Versus Heroin

Though Sessions’ claim that marijuana is “only slightly less awful” than heroin is subjective, it runs counter to the opinion of experts.

In a study published in The Lancet in November 2010, David Nutt, a professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, and other members of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, a group of drug experts in the U.K., ranked 20 drugs based on 16 criteria.

In a study published in The Lancet in November 2010, David Nutt, a professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, and other members of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, a group of drug experts in the U.K., ranked 20 drugs based on 16 criteria.

The criteria took into consideration both the harm the drugs do to users and to society, including lethal overdose potential, abuse and addiction potential, damage to physical and mental health, economic cost, link to crime, environmental damage, and family dysfunction. The researchers also considered the extent to which a drug is used in the U.K.

On a scale of 1 to 100, marijuana ranked eighth most harmful with a score of 20. Heroin came in second place with a rating of 55. Alcohol was the most harmful drug, according to the experts, with a harm rating of 72, while mushrooms ranked last with a score of 6. A large chunk of alcohol’s overall score came from harm it did to society, although alcohol also ranked fourth in terms of the harm it does to users. Heroin, on the other hand, was the second most harmful drug to users and the third most harmful to society.

To be clear, the researchers ranked drugs for the U.K. in particular. Since no ranking of this sort has been done for the U.S., we reached out to Nutt by email to ask him if the U.K. rankings could translate to the United States. He said largely yes, but “if anything with the legalisation of medical [marijuana] in the USA, cannabis would be even lower in harm than in our ratings.” He added, “Heroin would stay about the same.”

When we asked why, he told us that marijuana legalization eliminates “black market harms,” which means that there would be less harm related to crime, for example. Marijuana is currently illegal in the United Kingdom. Heroin, on the other hand, would likely have a similar rating because the U.K. is also currently experiencing a heroin epidemic, he said.

However, some researchers, including Jonathan P. Caulkins, a professor of public policy at Carnegie Mellon University, have argued that ranking drugs under a single measure obscures the nuance behind how and why certain drugs are harmful.

So let’s go over a few specifics.

First off, no one has ever died of a marijuana overdose, but nearly 13,000 people died of heroin overdose in the U.S. in 2015 alone. According to the National Cancer Institute, the receptors in the brain activated by marijuana aren’t located in the brainstem regions that control respiration, while those activated by heroin and other opioids are. This means that “lethal overdoses” from marijuana don’t occur, says the NCI.

Second, heroin is highly addictive, whereas only about 1 in 10 marijuana users become addicted, according to the CDC. Withdrawal symptoms of heroin include muscle and bone pain, sleep problems, diarrhea, vomiting, cold flashes and uncontrollable leg movements. Withdrawal symptoms of marijuana include grouchiness, sleep problems, decreased appetite and anxiety. In other words, marijuana withdrawal “symptoms appear to be mild compared with withdrawal symptoms associated with opiates,” adds the NCI.

Intravenous heroin use, which is the most common means of taking the drug, can also put people at risk for HIV, hepatitis C and other infections. Marijuana is typically smoked, but there isn’t conclusive evidence to suggest that it can cause lung cancer, though there is some association with testicular cancer. However, studies have shown that smoking marijuana can impact heart rate and blood pressure, which means it may increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes, says the CDC.

Lastly, it’s important to note that marijuana and heroin are both classified as Schedule 1 drugs by the Drug Enforcement Administration. This means the DEA sees them “as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” This is also despite the fact that Chuck Rosenberg, the head of the Drug Enforcement Agency in 2015, has said that “heroin is clearly more dangerous than marijuana.”

In short, marijuana isn’t harmless, but experts agree it’s considerably less harmful than heroin.

Marijuana and Opioids

Currently, 28 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana in some form, while eight states and D.C. have legalized marijuana for recreational use.

We reached out to the Justice Department to ask if Sessions meant medical or recreational marijuana when he said he is “astonished to hear people suggest that we can solve our heroin crisis by legalizing marijuana.” But we have yet to receive a response. We’ll update this article, if we do.

There’s no research suggesting legalizing recreational marijuana will “solve” the heroin crisis, but there is evidence backing the idea that medical marijuana may help curb the opioid epidemic more broadly.

For example, Marcus A. Bachhuber, now a doctor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and others found that states with medical marijuana laws had an almost 25 percent lower annual rate of opioid overdose deaths on average between 1999 and 2010 than states without such laws. Three states had medical marijuana laws prior to 1999 and 10 additional states implemented laws during the course of the study. The group looked at all 50 states.

Published in JAMA Internal Medicine in October 2014, the study also found that the association between medical marijuana legalization and reductions in opioid overdose deaths generally improved over time. There was a little less than a 20 percent reduction in deaths after the first year of the medical marijuana law’s implementation and a more than 33 percent reduction after six years of implementation, the study found.

And when the researchers conducted additional analyses that included heroin overdose deaths, they got similar results — a 23 percent lower annual rate of deaths.

Another study published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence in February 2017 found medical marijuana legalization was associated with a 23 percent reduction in hospitalizations for opioid-related dependence or abuse and a 13 percent reduction in hospitalizations for opioid-related overdoses between 1997 and 2014, compared with states that hadn’t legalized marijuana.

Conducted by Yuyan Shi, a professor of medicine and public health at the University of California, San Diego, the study did conclude that it’s “premature to advocate medical marijuana legalization as a strategy to curb” opioid abuse and overdose. Shi argued this last point, in part, because the causal mechanisms to explain the relationship between opioid and marijuana use have yet to be fully fleshed out.

However, a study by Ashley C. Bradford and W. David Bradford, a master’s student and a professor of public policy, respectively, at the University of Georgia, provides evidence for one causal explanation — people may be swapping opioids for marijuana.

Published in Health Affairs in July 2016, the study investigated whether medical marijuana laws affected “prescribing patterns” between 2010 and 2013 in “Medicare Part D for traditional (FDA-approved) drugs that treat conditions marijuana itself might treat.” Part D is the prescription drug program for Medicare, which is available to individuals 65 and older and certain younger individuals with disabilities. State medical marijuana legislation, which the researchers reviewed, also notes specific conditions that medical marijuana might be able to treat.

Generally, the pair found that “prescription drugs for which marijuana could serve as a clinical alternative” fell significantly between 2010 and 2013 once a medical marijuana law was implemented. This was particularly the case for pain medications, including opioids, which dropped by 1,826 daily doses filled annually by doctors after medical marijuana laws were implemented.

The researchers “haven’t yet analyzed how many of those doses were opioid drugs versus other painkillers, but David Bradford suspects it’s a large chunk,” reported Science in November 2016. “It’s suggestive evidence that medical marijuana might help divert people away from the path where they would start using [an opioid drug], and of course if they don’t start, they’re not on that path to misuse and abuse and potentially death,” he told Science.

It’s also important to note that the study estimated that, nationally, the Medicare program and its enrollees spent over $515 million less between 2010 and 2013 “as a result of changed prescribing behaviors induced by seventeen states and the District of Columbia — the jurisdictions that had legalized medical marijuana by then.”

One limitation of the study is that it looks at primarily older individuals, which may not be representative of marijuana and opioid users as a whole. However, the researchers also told Science that they’re in the process of publishing a follow-up study that looks at medical marijuana legislation’s effect on prescription patterns for Medicaid recipients.

Younger individuals are eligible for Medicaid, including those who are low-income or disabled. So far, the drop in pain medication prescriptions appears to be even more significant than that for Medicare, Bradford told Science.

An additional study backs up the Bradford study.

In June 2016, Daniel J. Clauw, the director of the Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center at the University of Michigan, and others published research that looked at patterns of prescription opioid and medical marijuana use in 244 individuals with chronic pain surveyed between 2013 and 2015.

Published in The Journal of Pain, the study found that marijuana use was associated with 64 percent less opioid use in patients with chronic pain. The researchers also found marijuana use “was associated with better quality of life” in 45 percent of the individuals surveyed.

The CDC also states, “Although prescription opioids can help manage some types of pain, there is not enough evidence that opioids improve chronic pain, function, and quality of life.” The CDC adds that “long-term use of opioid pain relievers for chronic pain can be associated with abuse and overdose, particularly at higher dosages.”

And there is still more research that supports the idea that medical marijuana may help curb the opioid epidemic.

While these studies primarily looked at prescription opioids — that is, not heroin — there’s a relationship between prescription opioid use and heroin use. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 79.5 percent of “recent heroin initiates” previously used prescription opioids and 31.3 percent previously abused or were addicted to prescription opioids.

For this reason, the CDC says that past “misuse of prescription opioids is the strongest risk factor for starting heroin use.” However, the CDC adds, “Increased availability, relatively low price (compared to prescription opioids), and high purity of heroin in the U.S. also have been identified as possible factors in the rising rate of heroin use.” For example, the DEA confiscated less than 500 kilograms of heroin between 2000 and 2008 on the southwest border of the U.S., compared with 2,196 kilograms in 2013.

So while marijuana may not be the silver bullet for the heroin crisis, or the opioid epidemic more broadly, there is some evidence that medical marijuana may help.

Editor’s Note: SciCheck is made possible by a grant from the Stanton Foundation.