Sen. James Inhofe misleadingly claimed that the statistics behind the globe’s likely hottest years on record — 2014, 2015 and 2016 — were “meaningless” because the temperature increases were “well within the margin of error.” Taking into account the margins of error, there’s still a long-term warming trend.

Inhofe, a longtime skeptic of human-caused climate change, made his claim Jan. 3 on the Senate floor.

Inhofe, Jan. 3: The Obama administration touted 2014, 2015, and 2016 as the hottest years on record. But the increases are well within the margin of error. In 2016, NOAA said the Earth warmed by 0.04 degrees Celsius, and the British Government pegged it at 0.01 Celsius. However, the margin of error is 0.1 degree, not 0.01. So it is all statistically meaningless and below the doom-and-gloom temperature predictions from all the various models from consensus scientists.

Since Inhofe cites data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the British government, we’ll concentrate on their analyses.

According to NOAA, 2016 was the warmest year on record for the globe since record keeping began in 1880; 2015 ranked the second warmest year and 2014 the third warmest. There are uncertainties in those rankings, however.

According to NOAA, 2016 was the warmest year on record for the globe since record keeping began in 1880; 2015 ranked the second warmest year and 2014 the third warmest. There are uncertainties in those rankings, however.

As we explained in 2015 when then-President Obama proclaimed 2014 “the planet’s warmest year on record,” such a definitive claim is problematic. For instance, while NOAA found then that 2014 had the highest probability of being the warmest, there remained statistical odds that other years could have held that distinction. But as we explained, scientists are more concerned with long-term trends than any given year.

And 2017 is on track to be another warm year. On Dec. 18, NOAA said 2017 could end up being the third warmest on record, based on data for January to November. NOAA spokesman Brady Philips told us the agency will release information on the year as a whole on Jan. 18.

Update, Jan. 18: NOAA has confirmed 2017 was likely the third hottest year on record since record keeping began in 1880. On Jan. 18, the agency said 2017 was 0.84 C (1.51 F) warmer than the 20th century mean, with a margin of error of plus-or-minus 0.15 C (0.27 F).

NOAA ranks years by looking at how much their average temperatures differ from the 20th century average — what scientists call a temperature anomaly.

Based on the agency’s analysis, the average temperature for 2016 was 0.94 degrees Celsius (1.69 degrees Fahrenheit) above the 20th century average of 13.9 C (56.9 F). The margin of error for 2016 was plus-or-minus 0.15 C (0.27 F).

NOAA explains that a margin of error takes into account the “inherent level of uncertainty” that comes with “[e]valuating the temperature of the entire planet.”

The agency adds that the reported temperature anomaly — 0.94 C in the case of 2016 — “is not an exact measurement; instead it is the central — and most likely — value within a range of possible values.”

For example, that range, or margin of error, would be 0.79 C (1.42 F) to 1.09 C (1.96 F) for 2016. Scientists at NOAA are 95 percent certain the temperature anomaly for 2016, or for any given year, will fall within the margin of error.

As Inhofe notes, NOAA scientists found that the average temperature for 2015 was 0.04 C less than 2016’s at 0.90 C (1.62 F) above the 20th century norm. The margin of error for 2015 was plus-or-minus 0.08 C (0.14 F), which means the range for 2015 is between 0.82 C (1.48 F) and 0.98 C (1.76 F).

The difference between 2015 and 2014, however, was wider. The average temperature for 2014 was 0.74 C (1.33 F) above the 20th century mean, or 0.16 C (0.29 F) less than 2015. The range for 2014 is between 0.59 C (1.06 F) and 0.89 C (1.60 F).

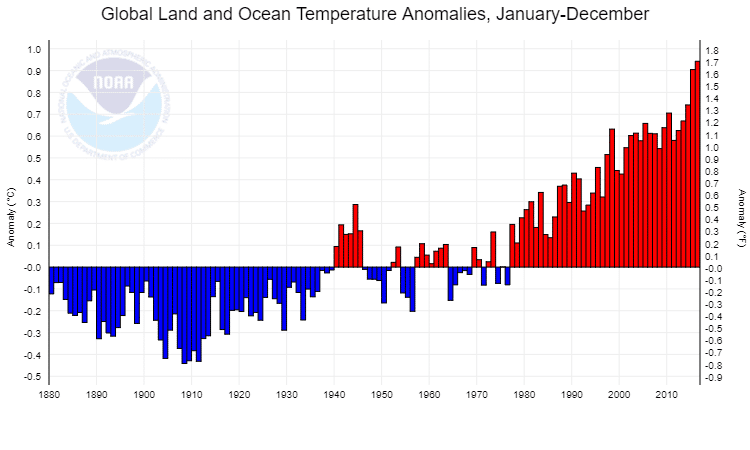

So the margins of error for these three years do overlap. When we requested evidence from Inhofe’s office, spokeswoman Leacy Burke sent us links to articles that reiterate the senator’s claim that the temperature increase in 2016 was within a margin of error – meaning, again, that while 2016 is most likely the warmest on record, other years that fall within that margin, including 2015 and 2014, could be the warmest. Still that doesn’t mean the statistics are “meaningless.” Over the long haul, data show an increasing trend, as the chart below shows.

“Overall, the global annual temperature has increased at an average rate of 0.07°C (0.13°F) per decade since 1880 and at an average rate of 0.17°C (0.31°F) per decade since 1970,” says NOAA.

Similar to NOAA, the U.K.’s Met Office, the country’s national weather service, reported that 2016 “was one of the warmest two years on record, nominally exceeding the record temperature of 2015.” The agency also found that 2014 likely ranked the third warmest year.

Both NOAA and the Met Office note that human-caused global warming isn’t the only force behind the record temperatures.

Peter Stott, then the acting director of the Met Office Hadley Centre, said: “A particularly strong El Niño event contributed about 0.2C to the annual average for 2016, which was about 1.1C above the long term average from 1850 to 1900.” El Niño is a naturally occurring interaction between the atmosphere and ocean that is linked to periodic warming.

Stott added, “However, the main contributor to warming over the last 150 years is human influence on climate from increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.”

The Met Office’s numbers differ slightly from NOAA’s, in part, because the agency uses a different reference point.

NOAA ranks years based on how much their average temperatures differ from the 20th century norm. The Met Office uses the temperature average between 1850 and 1900 or between 1961 and 1990.

Using that latter reference point, the Met Office found 2016’s temperature anomaly to be 0.77 C, plus-or-minus 0.1 C, which was only 0.01 more than 2015’s temperature anomaly.

So Inhofe is right that the British government’s margins of error for 2016 and 2015 overlap.

But Grahame Madge, a spokesman for the Met Office, explained in an email to us why it’s important to look at the long-term trend — not just the difference between two years, as Inhofe did.

Madge, Jan. 6: When looking at global temperature rise it helps to look at the way the stats and figures are framed. For example, 2016 was the warmest year since pre-industrial times. However, it was only marginally warmer than the previous year, which was also a record. When viewed as parallel years, however, they really stand out in the long-term record. … We try to focus on the long term when presenting information. You can make a desert seem like a lush wetland if you only show the oasis.

NOAA also explains the difference between looking at single years versus the long-term trend: “As more and more data builds a long-term series, there is less and less influence of single ‘outliers’ on the overall trend, making the long-term trend even more certain than the individual points along it.”

In other words, if scientists found that the globe had just one year with an exceptionally high temperature average, they may not be convinced that global warming is occurring. But if data show that the planet has experienced a number of record warm years in a row, it suggests the warming trend is real.

In fact, NOAA says there’s only a 0.0125 percent chance of seeing three outliers in a row — and the Earth has seen many more record warm years than three.

NOAA writes that 2016 “marks the fifth time in the 21st century a new record high annual temperature has been set (along with 2005, 2010, 2014, and 2015) and also marks the 40th consecutive year (since 1977) that the annual temperature has been above the 20th century average.”

So while Inhofe was right that the margins of error for temperature measurements in recent years overlap, that doesn’t negate a long-term warming trend or render the temperature anomalies “meaningless.”

Editor’s Note: SciCheck is made possible by a grant from the Stanton Foundation.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: