The Line: The top 1 percent will get 83 percent of the tax cuts under the new tax law.

The Line: The top 1 percent will get 83 percent of the tax cuts under the new tax law.

The Party: Democratic

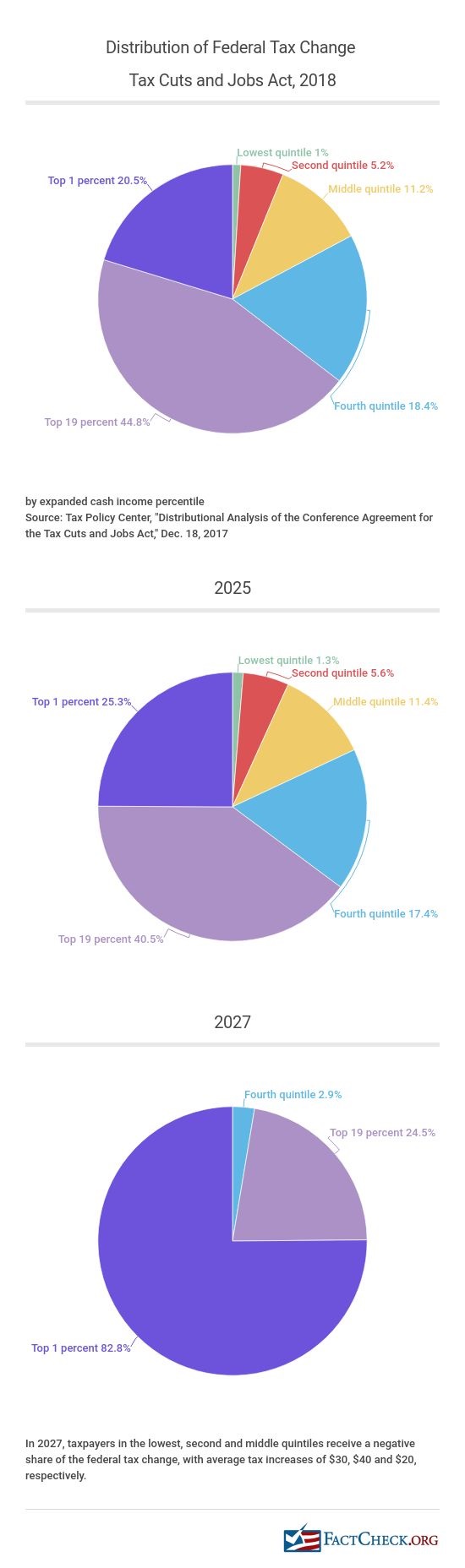

The Republican tax plan was signed into law just last month, and Democrats already have a well-worn, and misleading, talking point about it: 83 percent of the tax cuts go to the wealthiest 1 percent. That’s true for 2027 but only because most of the individual income tax changes expire by then.

In 2025 — the last year before those tax changes expire — a quarter of the tax cuts go to the top 1 percent.

It’s a classic case of politicians using a technically accurate statistic but without the context or explanation it requires. Without all the facts, the talking point leaves a misleading impression.

Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio used a version of the tax line in a Jan. 23 press availability, saying that “more than 80 percent of that tax cut went to the — goes to the wealthiest 1 percent.” But he’s part of a long list of Democrats who favor the phrase.

House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi repeatedly has said that “83 percent of the benefits go to the top 1 percent.” It’s a line included in Senate press releases and emphasized three times in one Democratic press availability in late December, by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (twice) and Sen. Bernie Sanders, who did note that this was “at the end of 10 years” and that the “middle class” tax breaks “expire at the end of eight years.”

The important missing context is that the final tax legislation, which President Donald Trump signed into law Dec. 22, allows most of its individual income tax provisions to expire by 2027, making the tax benefit distribution more lopsided for the top 1 percent than in earlier years.

In 2018, according to an analysis by the Tax Policy Center, the top 1 percent of income earners would glean 20.5 percent of the tax cut benefits — a sizable chunk, but far less than the figure that’s preferred by Democrats. And in 2025, that percentage would be 25.3 percent, with the top 1 percent (those earning above $837,800) getting an average tax cut of $61,090.

Just two years later, in 2027, the percentage of tax benefits to this income group jumps to 82.8 percent, “because almost all individual income tax provisions would sunset after 2025,” explains TPC. The top 1 percent still benefits from some of the remaining tax cuts, such as reducing the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. But their average tax cut drops by nearly two-thirds to $20,660 in 2027.

So while a lot more of the benefits go to the top 1 percent that year, there are fewer benefits to go around. Without those individual income tax provisions, all taxpayers see an average $160 tax cut in 2027, while the average tax cut for all taxpayers in 2025 is $1,570.

Why do these individual tax cuts expire in the law? Republicans say they expect a future Congress will extend those cuts, rather than allowing taxes for many to increase. But in order to pass their tax bill through budget reconciliation, a process requiring only a majority vote in the Senate, Republican lawmakers could not add more than $1.5 trillion to the deficit over 10 years. Nor could they have a bill that added to the deficit beyond that 10-year window.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget calls the expiring cuts “gimmicks.” It notes that “the ‘easy’ options” for Republicans to make the final bill meet those requirements were to have some of the tax cuts expire — and that’s what GOP lawmakers did. While the final bill costs an estimated $1.46 trillion over 10 years, CRFB says the actual cost could end up being $2.2 trillion, when these sunsetting tax cuts are actually extended.

One might argue the Republicans practically wrote this talking point themselves by constructing the legislation this way. The Tax Policy Center and other groups that analyze such legislation had to provide the relevant figures for 2027.

“The effect of turning off those individual income tax cuts would be dramatic,” TPC senior fellow Howard Gleckman wrote. “Households making less than $155,000 in 2027 would get no tax cut at all, on average. And more than half of all households would pay more in taxes than under the pre-TCJA, mostly because the new law permanently shifts to a less generous method for indexing the tax code for inflation. As a result, nearly 83 percent of all the benefits of the TCJA in 2027 would go to the top 1 percent of households.”

A spokesperson for the Democratic minority on the Senate Finance Committee told us that this statistic is “a key data point to our argument that Republicans’ tax law is an economic double standard. … The fact is, Republicans chose to make permanent massive tax cuts for multinational corporations while writing tax cuts for middle class families in disappearing ink.”

But Democrats are giving voters a misleading view of the new law’s impact. The proportion of tax benefits going to the top 1 percent is much lower in earlier years — before the individual tax cuts expire — than this talking point reveals.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: