The United States had a trade surplus with China for passenger cars of $8.9 billion in 2017. Exports of cars to China totaled $10.5 billion, while imports from China were $1.6 billion. Yet President Donald Trump claimed that China “won’t take” U.S. cars.

The president made his claim during a roundtable discussion about taxes in West Virginia on April 5. He said: “If we make a car and try and get it into China, number one, they won’t take it. But if they did, it’s 25 percent tax. So they pay 2.5; we pay 25. They don’t even want to take it. That doesn’t sound so good.”

Trump is correct on the countries’ respective tariffs, but despite that imbalance, U.S. automakers export a lot more cars to China than China sends to the U.S.

Is China refusing to “take” U.S. cars?

“It’s nothing I’ve heard of before,” said Kristin Dziczek, vice president of industry, labor and economics at the Center for Automotive Research, an independent, nonprofit research center. She told us the forecast is for the U.S. to export about 250,000 cars to China this year.

China, in fact, is the second largest market for U.S. exported cars, behind Canada, according to data from the Census Bureau’s foreign trade division.

Two other experts also questioned the president’s claim about China not wanting to take U.S. cars.

“That isn’t really true,” Brad W. Setser, the Steven A. Tananbaum senior fellow for international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations, told us in an email. “Mercedes, BMW and Jeep/ Chrysler all have exported cars from the US to China successfully.”

General Motors and Ford have long-established joint ventures with Chinese businesses in that country, Setser said, allowing them to manufacture cars there and avoid the tariff. “They consequently haven’t really looked to export from the US to China,” he said.

Marina v.N. Whitman, a former vice president at the General Motors Corp. and professor emerita of business administration and public policy at the University of Michigan, told us there was a “kernel of truth” in Trump’s full statement, “but it is combined with a lot of misrepresentation and or downright falsehoods.”

She said that it’s “absolutely true” that “we have an ongoing beef against China for the way in which it has forced the transfer of American technology to China in an attempt to catch up and get ahead of us.” China requires U.S. companies manufacturing cars in that country to enter into a joint venture with a Chinese company.

But in terms of Trump’s statement that China “won’t take” U.S. cars, Whitman said the substantial amount of U.S. car exports to China “certainly doesn’t indicate that they aren’t taking them.”

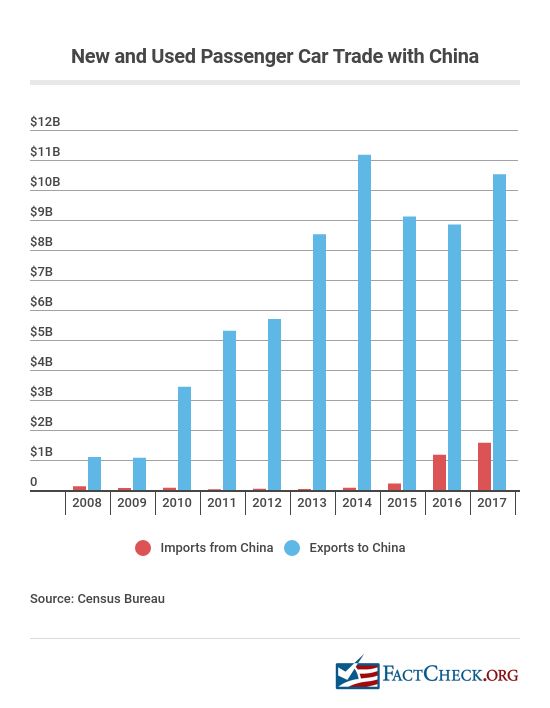

Here’s the balance of trade in new and used passenger cars from 2008 to 2017, according to foreign trade statistics from the Census Bureau.

We asked the White House press office for support for the president’s claim, but it didn’t provide any.

Some have argued that China should change its tariff on car imports, among other measures. New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman wrote about “a real trade problem with China” last month and cited those lopsided tariff numbers.

Those tariffs were set through membership in the World Trade Organization, Dziczek explained, with the idea being that developing markets “could set more protective barriers” to allow them to grow their industries. China is the largest automotive producer in the world, however, and has been since 2009.

Many of the cars the U.S. exports to China are luxury vehicles or iconic cars, where that 25 percent tariff “can be borne by that customer on the other end,” Dziczek said.

On April 10, Chinese President Xi Jinping did say China would “significantly lower” its tariffs on imported cars in general. CNN noted, however, that China made a similar statement in November.

U.S. exports to China increased significantly from 2010 to 2014 and then leveled off, but in 2016 and 2017 the small number of cars imported from China has grown. “Over the last few years, Chinese demand growth has cooled and investment in China has caught up with Chinese demand,” Setser told us, “and there is a general incentive to manufacture more in China to jump over the tariff so long as a firm isn’t scared off by the JV requirement.”

That joint-venture requirement calls for a U.S. company operating in China to establish a partnership with a Chinese business.

“Since 1983, any foreign automaker that has wanted access to the local market has had to set up a JV with a domestic firm, in which the Chinese ownership must be at least 50%,” explains a report by the Economist Intelligence Unit for PwC on setting up partnerships in the country.

Foreign companies have set up shop in China, including U.S.-based companies. In fact, the trade ratio is expected to change “quite dramatically,” Dziczek told us, with imports from China surpassing exports to China by 2022. The amount of cars China sends to the U.S. is expected to grow from 58,000 in 2017 to about 450,000 by then and top 500,000 in 2024. But it won’t be Chinese-branded vehicles fueling that; it’s international producers who will send Fords, Buicks, Volvos to the U.S., she said.

Trump is right about the tariff imbalance between the two countries. Setser writes in a blog post on the topic that the tariff is a “real barrier” and “clearly encourages production in China for the Chinese market.” But China does take U.S. cars, contrary to Trump’s statement, and in fact is one of the largest markets for U.S. cars.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: