President Donald Trump implied that his administration’s funding to fight the opioid epidemic had caused the “numbers” to come “way down.” But the most recent data we have on opioid-related deaths — which are still rising — and prescriptions for opioids — which have been declining in recent years — predate the funding the president touted.

Trump made his claim in Nashville during a campaign rally on May 29.

Trump, May 29: We got $6 billion for opioid and getting rid of that scourge that’s taking over our country. And the numbers are way down. We’re getting the word out — bad. Bad stuff. You go to the hospital, you have a broken arm; you come out, you’re a drug addict with this crap. It’s way down. We’re doing a good job with it.

The $6 billion was for a two-year period, fiscal 2018 and 2019. It was included in a federal budget deal signed in February this year. At the end of March, Congress appropriated $3.6 billion of that for fiscal 2018, which ends Sept. 30.

Asked what “numbers” the president was talking about, the White House press office referred us primarily to figures on opioid prescriptions. The latest figures, however, only encompass 2017 — Trump’s first year in office and before the funding the president cited was even appropriated. Some official figures only date to 2016, before Trump was in office.

Overall, dispensed prescriptions for opioids have been declining in recent years. Total deaths from opioid overdoses have continued to increase, though that has been driven primarily by illicit, not prescription, opioid use.

Let’s take a closer look at the available statistics.

Opioid Prescriptions

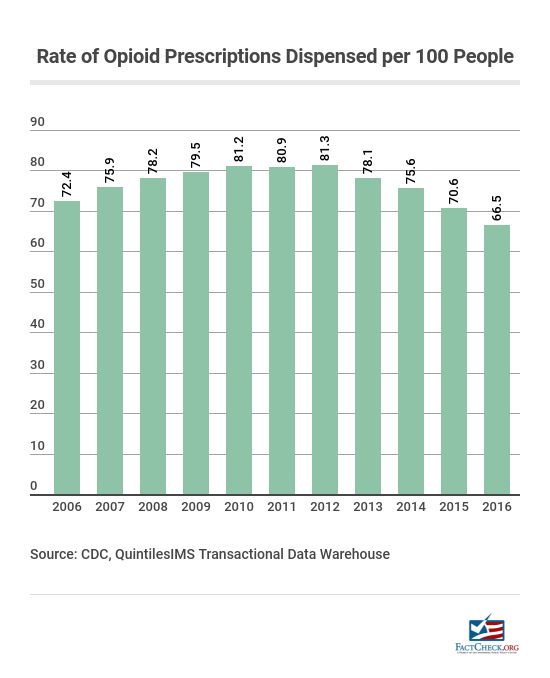

The latest figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the 2006-to-2016 time period show the total number of opioid prescriptions and the prescribing rate increased from 2006 to 2012, before beginning to decline. In 2012, the number of dispensed prescriptions peaked at more than 255 million, and by 2016, the number had dropped to more than 214 million. The rate of 81.3 prescriptions per 100 people in 2012 was down to 66.5 per 100 people in 2016, “the lowest it had been in more than 10 years,” the CDC said.

Still, the CDC said, the “prescribing rates continue to remain very high in areas across the country,” noting that in about 25 percent of counties across the country, the number of prescriptions dispensed amounted to one for every person.

The White House press office cited the CDC statistics, though Trump’s policies couldn’t have had an impact in 2016.

The most recent figures, which the White House also cited, come from a report by IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science, an independent organization. Those figures date to 1992 and show that the volume of opioid prescriptions had been going up from that year until it hit a peak in 2011 (one year earlier than the CDC measurements show). The volume has declined by 29 percent since then through 2017, with the drop in 2017 at 12 percent from January to December, the largest decrease in one year.

The volume is defined by morphine milligram equivalents.

Why has there been a decrease? The report said the drop has been driven by “changes in clinical usage, which have been influenced by regulatory and reimbursement policies and legislation that have been increasingly restricting prescription opioid use since 2012.” In 2016 and 2017, seven states added laws on restricting prescriptions, such as the volume or number of days opioids can be prescribed to new patients. A total of 24 states now have such laws, the report said.

“At the federal level,” the report said, “the passage of two new laws in the past two years [2016 and 2017] and the founding of a presidential commission have added to the attention and focus nationally on opioid issues.”

Trump established the commission by executive order on March 29, 2017, and it held its first meeting on June 16 that year.

It’s certainly possible that opioid prescriptions will continue to decline under Trump. The president’s actions are part of a yearslong focus by government, health care practitioners and the industry, and insurers to combat the opioid addiction epidemic.

By 2010, “alarm about the opioid epidemic” began “growing in public health circles,” a 2017 report by the National Academy of Sciences says. Medical organizations and the government urged caution in prescribing the drugs.

In 2011, for example, the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Health and Human Services and other agencies launched initiatives to advance safe use, disposal and prescribing of opioids.

In May 2016, the insurer Cigna set a goal of reducing opioid use by 25 percent by 2019. It announced this March that it had achieved that goal one year ahead of schedule, “in partnership with more than 1.1 million prescribing clinicians.”

Opioid Overdose Deaths

More than 42,000 people died of overdoses related to prescription and illicit opioids in 2016 — five times more than in 1999, according to figures from the CDC, and more than those who died in car accidents in 2016, according to data from the National Safety Council.

The CDC’s provisional numbers for 2017 show a continued increase in opioid overdose deaths — to 46,041 for the 12 months ending in October 2017, though the CDC warns that the total is “likely underreported due to incomplete data.” That’s up from 43,639 for the 12 months ending in January 2017, when Trump took office. The CDC number for that month carries the same warning.

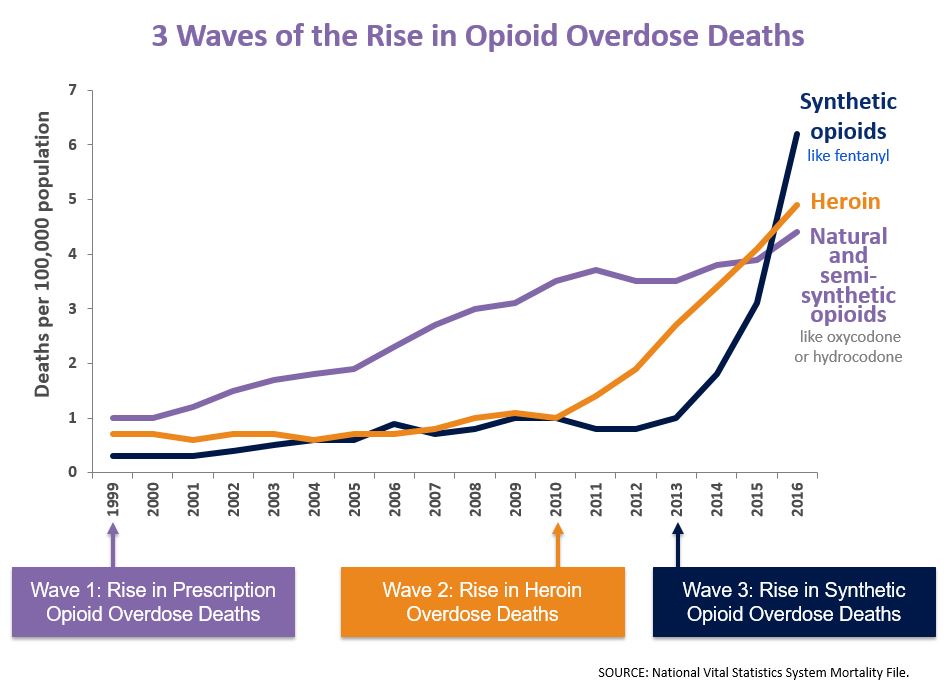

The continued increase has been driven by illicit opioid use.

Between 1999 and 2011, the number of deaths related to prescription opioids rose from more than 5,000 to around 17,500 per year, according to the 2017 National Academy of Sciences report.

But as dispensed prescriptions declined, the rise in yearly deaths related to prescription opioids slowed. Between 2011 and 2015, the number has “remained relatively stable,” the NAS report adds. However, “overdose deaths from illicit opioids (including heroin and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl) nearly tripled during this time period, driven in part by a growing number of people whose use began with prescription opioids.”

The CDC says that fentanyl, an extremely strong opioid, is driving the increases. Fentanyl — which is a prescription opioid, but can also be manufactured illegally — is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

To be clear, it’s often difficult to pinpoint which drug caused the fatal overdose because people who have died often test positive for multiple drugs; for example, both heroin and a prescription opioid, or heroin and a non-opioid, such as cocaine. That’s why experts say deaths are opioid-related.

The White House press office also cited a February article by the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Stateline project. It said that while drug overdose deaths had increased steadily in “nearly every state” since the late 1990s, provisional CDC data had shown a decline in overdose deaths in 14 states for the 12-month period that ended in July 2017. The article said those figures had “prompted cautious optimism among some public health experts.”

Several other states, though, saw “death spikes of more than 30 percent,” the article noted.

Plus, those figures cover a 12-month period that spanned both the Obama and Trump administrations, evenly.

In other words, they, too, are no indication that the $6 billion in funding Trump cited had caused any opioid epidemic numbers to come “way down.”

— Lori Robertson and Vanessa Schipani