Democratic Sen. Kamala Harris made a few false and misleading claims in two events that kicked off her 2020 presidential campaign.

- In a speech in her home state of California on Jan. 27, Harris said “paychecks aren’t keeping up” with the cost of living. But Bureau of Labor Statistics data show inflation-adjusted weekly earnings have gone up in the past year and since President Donald Trump took office.

- She also claimed the administration had given “a trillion dollars to the biggest corporations in this country,” a reference to the 10-year impact of the corporate tax rate reduction in the 2017 tax law. The net tax reduction to businesses, however, was an estimated $653.8 billion.

- In a CNN town hall on Jan. 28, Harris said she “did not oppose” legislation, as the California attorney general, that would have required her office to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate fatal police shootings. In fact, she said such a law was unnecessary.

Harris this week joined a growing number of Democrats who say they will run for the party’s presidential nomination. After making her announcement in California, the senator went to Des Moines, Iowa, the next day for a televised town hall meeting hosted by CNN’s Jake Tapper.

Wages Have Gone Up

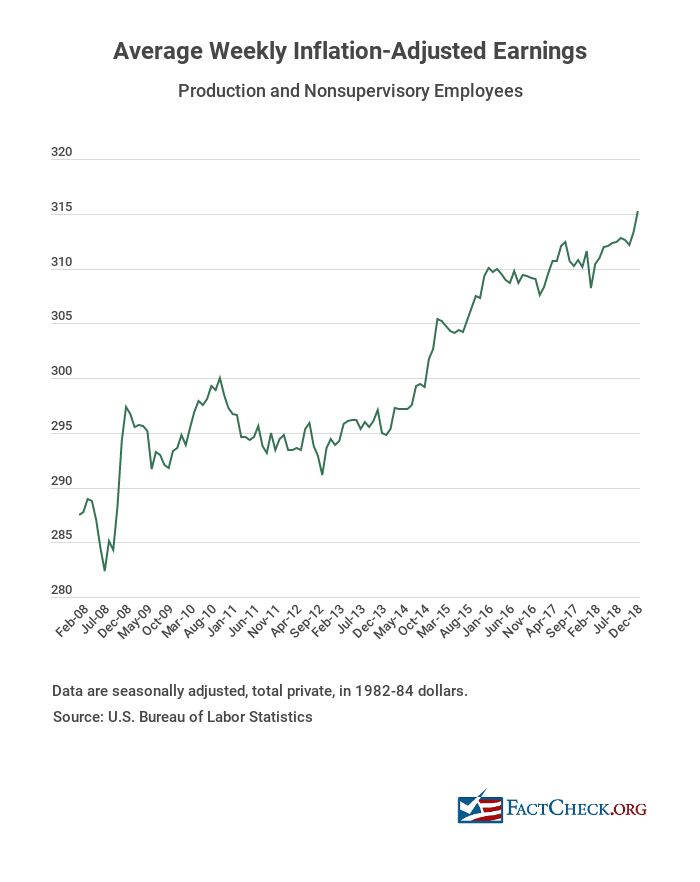

Harris told the crowd in Oakland that paychecks weren’t keeping pace with the increasing cost of living. But weekly earnings, in inflation-adjusted dollars, have been going up under the Trump administration.

Harris, Jan. 27: Our economy today is not working for working people. The cost of living is going up, but paychecks aren’t keeping up.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, real (meaning, inflation-adjusted) average weekly earnings for rank-and-file production and nonsupervisory workers have gone up 2.5 percent since President Donald Trump took office. Those earnings rose 4.7 percent during Barack Obama’s last four years as president.

The average real weekly earnings of all private-sector workers have increased by 2.4 percent during Trump’s tenure; they went up 3.9 percent in the previous four years.

So, paychecks, on average, have kept up with rising inflation.

Here’s the chart on rank-and-file weekly earnings:

In January, BLS said that real average hourly earnings for all employees went up 1.1 percent and for production and nonsupervisory employees 1.5 percent for the 12 months ending December 2018. For real average weekly earnings, the increase was 1.2 percent for both groups.

When we asked the Harris campaign about the senator’s claim, it pointed to a CBS News article from July, which said, “Average hourly earnings in June grew just 2.7 percent from the year before — slower than the rate of inflation.” At the time, BLS said the average hourly earnings, adjusted for inflation, were “unchanged” for all workers, though they dropped 0.2 percent for the 12-month-period ending in June for rank-and-file workers.

BLS’ latest figures show wages outpacing inflation, however.

The campaign also pointed to a different metric: a look at the buying power of wages in the late 1970s compared with today. In an August report, the Pew Research Center said, “After adjusting for inflation, however, today’s average hourly wage has just about the same purchasing power it did in 1978, following a long slide in the 1980s and early 1990s and bumpy, inconsistent growth since then.”

Pew also found that the wage gains have disproportionately gone to higher-wage workers.

Pew Research Center, Aug. 7, 2018: Meanwhile, wage gains have gone largely to the highest earners. Since 2000, usual weekly wages have risen 3% (in real terms) among workers in the lowest tenth of the earnings distribution and 4.3% among the lowest quarter. But among people in the top tenth of the distribution, real wages have risen a cumulative 15.7%, to $2,112 a week – nearly five times the usual weekly earnings of the bottom tenth ($426).

But that doesn’t support the claim that wages aren’t keeping pace with the cost of living.

Tax Cut Cherry-Picking

Harris also exaggerated the tax savings for corporations under the Republican Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, signed into law in late December 2017.

Harris, Jan. 27: And when American families are barely living paycheck to paycheck, what is this administration’s response? … Their response is to give away a trillion dollars to the biggest corporations in this country.

According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provided a tax reduction over 10 years of a net $653.8 billion for businesses. Harris’ campaign confirmed to us that she was referring only to the law’s reduction of the top corporate tax rate, from 35 percent to 21 percent, which JCT estimates will reduce corporate taxes by $1.35 trillion over a decade.

But other provisions in the law that raised business taxes, such as changes in allowable deductions for net operating losses and interest, caused the net benefit for corporations to be hundreds of billions lower than that.

The individual income tax changes in the law amounted to an estimated $1.13 trillion tax reduction over 10 years, and overall, including changes to international taxes, the law would reduce taxes by $1.5 trillion over that time period.

Harris’ claim echoes past statements by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who misleadingly said last year that the tax law was “a $1.3 trillion tax break for corporations.” As we’ve said, the net benefit is about half that.

Plus, Eric Toder, co-director of the Tax Policy Center, told us when we wrote about this claim before that the $324 billion the international tax provisions would raise over 10 years would come “almost all from corporations.” Nearly all of that comes from a one-time, reduced rate on foreign profits that U.S. corporations have kept overseas.

Investigating Police Shootings

In the CNN town hall on Jan. 28, Tapper asked Harris about “criticism we’re hearing of you from the left” — specifically during her time as the state attorney general.

Tapper: [T]hey talk about things that you did as attorney general or as prosecutor or as a district attorney in San Francisco. Let me just ask about one of them.

Harris: Sure.

Tapper: Which is, when you were attorney general, you opposed legislation that would have required your office to investigate fatal shootings involving police officers. Why did you oppose that bill?

Harris: So, I did not oppose the bill. I had a process when I was attorney general of not weighing in on bills and initiatives, because as attorney general, I had a responsibility for writing the title and summary. So I did not weigh in.

That’s misleading. Harris may not have taken an official position on the bill, but she did oppose the concept of the bill. And her views on the topic were well known.

The bill — AB 86, sponsored by Assemblymember Kevin McCarty — would have required the attorney general to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate police shootings that involved the death of a civilian. It would have given the special prosecutor the authority to determine whether criminal charges should be filed.

The Assembly Committee on Public Safety approved the bill in April 2015, but it went no further.

At the time, Harris did not take an official position on McCarty’s bill. But she had already made clear that “she does not support the idea of taking prosecutorial discretion away from locally elected district attorneys,” the Capitol Weekly wrote in a May 18, 2015, story.

Capitol Weekly, May 18, 2015: [Harris] has said the current process of investigating civilian deaths by local law enforcement is effective enough. She also has said that the local district attorneys should have the authority to investigate officer-involved shootings, in part because they are elected by — and held accountable to — local constituents.

“I don’t think there’s an inherent conflict,” Harris said in an interview with The Chronicle back in December. “Where there are abuses, we have designed the system to address them.”

During that interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, Harris said, “I don’t think it would be good public policy to take the discretion from elected district attorneys.”

She told the Chronicle that the state didn’t need a mechanism for a special prosecutor, because “if I decided that there was a case where there was a local prosecutor who was breaking the law, who was committing prosecutorial misconduct, we would come in and take the case.”

McCarty, who supported Harris’ successful campaign for the U.S. Senate in 2016, told the Los Angeles Times in 2016 that he was disappointed that she didn’t support his bill.

Although Harris said her office had a policy of not taking a position on legislation, we found at least one example of her taking a position on a bill. In 2015, Harris opposed state legislation that would have imposed statewide standards for the use of body cameras on law enforcement officials — saying she didn’t want a “one-size-fits-all approach,” and preferred leaving such decisions up to local officials.

When we asked about Harris’ response to Tapper, her campaign told us that the senator “misheard the question.” She thought Tapper was asking about her position on a ballot initiative, and her office does not weigh in on ballot initiatives because it writes the title and summary, her campaign said. We note, however, that Harris immediately responded to Tapper’s question by saying, “I did not oppose the bill.” [Emphasis is ours.] It wasn’t until later in her response that she referenced ballot initiatives.

As for Harris’ position on the special prosecutor bill, her campaign said: “She didn’t take a position on the special prosecutor because she personally feels as the [Capitol Weekly] article says, ‘local district attorneys should have the authority to investigate officer-involved shootings, in part because they are elected by — and held accountable to — local constituents.'”

Correction, Jan. 30: Our original story included a typo. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provided a net tax reduction over 10 years for businesses of an estimated $653.8 billion, not million, as we originally wrote.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating:  FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: