President Donald Trump falsely claimed that El Paso went from “one of the most dangerous cities in the country to one of the safest cities in the country overnight” after “a wall was put up” along the Mexico border.

Here are the facts:

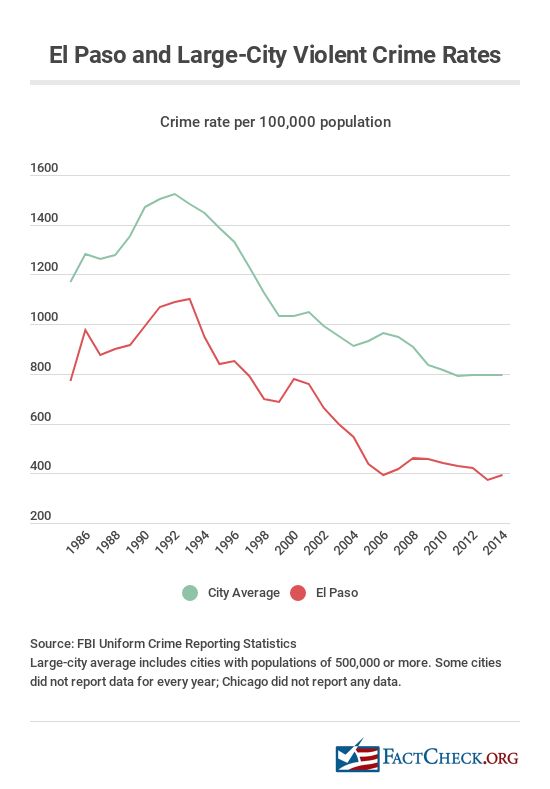

- El Paso has never been “one of the most dangerous cities in the country.” The city had the third lowest violent crime rate among 35 U.S. cities with a population over 500,000 in 2005, 2006 and 2007 – before construction of a 57-mile-long fence started in mid-2008.

- There was no “overnight” drop in violent crimes in El Paso after “a wall was put up.” In fact, the city’s violent crime rate increased 5.5 percent from 2007 to 2010 — the years before and after construction of the fence, which was completed in mid-2009.

- Along with the rest of the country, El Paso’s violent crime rate spiked in the early 1990s and has been trending downward ever since. The city’s violent crime rate dropped 62 percent from its peak in 1993 to 2007, a year before construction on the fence began.

The president, who is locked in a budget standoff with Congress over funding for his border wall, made his remarks about El Paso during a Jan. 14 speech at the American Farm Bureau Federation’s annual convention in Louisiana. Trump pointed to the border city as an example of the impact that a wall can have on crime.

Trump, Jan. 14: In El Paso … it was one of the most dangerous cities in the country. A wall was put up. It went from being one of the most dangerous cities in the country to one of the safest cities in the country overnight. Overnight. Does that tell you something?

No, it doesn’t tell us something.

There have been two pivotal changes in El Paso border enforcement over the last few decades, and neither lends itself to the president’s narrative. The first, in 1993, did not involve the erection of border wall, but rather a flood of border patrol agents along the immediate border.

The second was a border fence constructed as a result of the Secure Fence Act of 2006. But claiming that the construction of that fence transformed the city from one of the most dangerous in the country to one of the safest, as the president said, doesn’t hold up.

El Paso has long been a relatively safe city, even though it sits just across the Rio Grande River from sister city Ciudad Juarez, one of the most dangerous cities not only in Mexico, but in all of the world.

According to the Uniform Crime Reports from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the violent crime rate in El Paso historically has been well below the rate in other big cities in Texas, such as Houston, Dallas and Forth Worth, and has consistently been well below the national average for cities with 500,000 or more residents.

El Paso has had the lowest murder rate among the state’s six largest cities nearly every single year going back to 1985 (the earliest available year in the UCR’s online data tool, which goes through 2014). Its murder rate during that span was regularly four and five times lower than the rates in Houston, Dallas and Fort Worth. And for decades, it has had a murder rate far below the average among other large U.S. cities.

Crime did spike in El Paso in the early 1990s — as it did throughout the U.S. — peaking in 1993. That year, the violent crime rate for El Paso was 1,101.7 per 100,000 population. In the ensuing years, the violent crime rate began trending downward in keeping with the national trend, as our chart below shows.

Let’s take a look at the history of the federal government’s border control efforts in El Paso, the city’s crime statistics and border apprehension rates in the El Paso sector.

Operation Hold the Line

As we said, the spike and subsequent downturn in violent crime in El Paso mirrored a national trend. But there was also a border enforcement initiative in El Paso that began in 1993 and that researchers believe may have reduced petty crimes a bit.

In September of that year, U.S. Border Patrol implemented Operation Hold the Line. It marked a major change in border strategy, shifting agents from interior apprehension and removal, and instead flooding the border with agents to prevent entry in the first place. Agents were fanned out 24/7 across the El Paso border “close enough together to have visual contact with other agents on either side of them” to act as a blockade of sorts. Although no new fence was constructed, agents also repaired dozens of holes in the mostly chain-link fence that separated downtown areas of El Paso from Juarez.

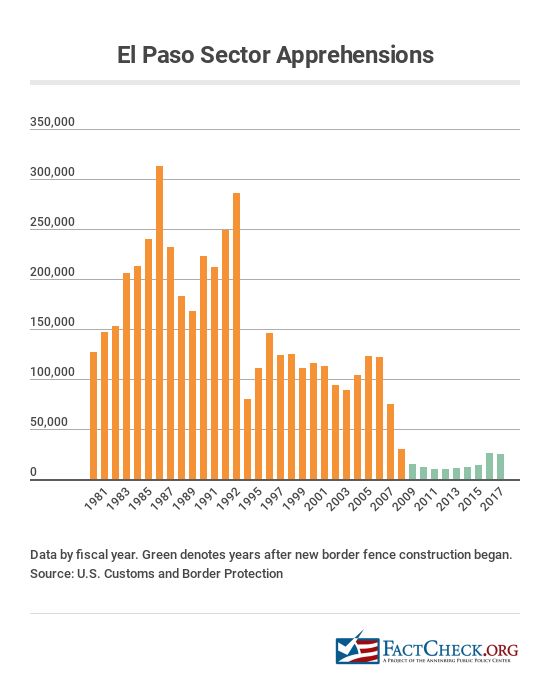

The impact on apprehensions was dramatic. According to data from U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, apprehensions declined more than 70 percent in one year, from 285,000 in 1993 to 79,000 in 1994, as the chart in the next section illustrates.

Research on the effects of the initiative conducted by professors at the University of Texas at Austin at the behest of the bipartisan U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform concluded that Operation Hold the Line was a substantial deterrent and dramatically reduced illegal border crossings in El Paso, particularly among local Juarez residents accustomed to easily crossing back and forth across the border. Long-distance labor migrants, however, simply traveled to crossing points in more remote areas along the Southwest border, the researchers found, and as a result, more people died attempting illegal border crossings in more dangerous terrain. Another consequence was that those who continued to cross illegally in El Paso stayed in the U.S. longer.

As for its effect on crime, the researchers found the operation “seems to have caused a reduction in petty crime (small-scale, low-level nuisance and property crimes), especially in downtown El Paso.” There was also a small reduction in other property and violent crime, the researchers said, though they cautioned that may have been the result of targeted police enforcement undertaken in the months after the operation began.

“The claim [Trump] is making is not justified by the available data,” one of the co-authors of the research paper, David Spener, now a professor at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, told us. While there was a drop in “annoyance crimes” directly across the border from Juarez, he said, there was no discernible effect on violent crime in El Paso, which “never had particularly high crime rates.”

Moreover, Operation Hold the Line was not a wall-building initiative.

“Operation Hold the Line redirected personnel from apprehension to deterrence. It certainly did not include a wall,” Susan Martin, who was the executive director of the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, told us via email. “The idea was that if the chance of apprehension rose to close to 100% through more strategic deployment of Border Patrol officers, people would be deterred from even attempting illegal entry. Beyond increasing the presence of BP officers, the strategy did include resources to repair holes in the existing fencing.”

As for a new fence, that came later.

Secure Fence Act of 2006

The president’s talking point may have been informed by recent comments from Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton. At a border security roundtable in McAllen, Texas, on Jan. 10, Paxton told Trump a border fence constructed under President George W. Bush transformed El Paso from one of the highest crime cities in the U.S. to one of the lowest. He’s wrong about that.

Paxton, Jan. 10: If you go to El Paso, we’ve put up a barrier there, I think it was under the Bush administration, it’s over one hundred miles long. El Paso used to have one of the highest crime rates in America. After that fence went up, and separated Juarez, which still has an extremely high crime rate, the crime rates in El Paso now are some of the lowest in the country. So we know it works. So the narrative is incorrect, and we’ve tested it in Texas.

About 57 miles of metal fence 15 to 18 feet high was constructed in and around El Paso as a result of the Secure Fence Act of 2006. Wall construction started in mid-2008 and finished in mid-2009, according to press accounts at the time.

Apprehensions of those attempting illegal border crossings did drop after the fence was constructed, but they also had been dropping pre-construction, data from CBP shows. Apprehensions dropped before construction of the fence from 122,679 in fiscal year 2005 to 75,464 in fiscal year 2007. Construction started in late FY2008, a fiscal year that saw apprehensions drop to 30,312; apprehensions dropped further to 14,999 in FY2009. Although border apprehensions were dropping nationwide during those years, the drop in El Paso’s apprehensions far outpaced the national average.

But FBI crime data belie the claim that a border wall transformed El Paso from one of the most crime-ridden cities in the country to one of the safest. Indeed, the violent crime rate increased 5.5 percent from 2007 to 2010 — the years before and after construction of the fence. Those years were not anomalies. Violent crime increased about 9.6 percent between 2006 and 2011 — two years before the fence construction began and two years after it was finished.

Last January, White House Press Secretary Sarah Sanders, echoed the president’s bogus talking point in a tweet: “Ask El Paso, Texas (now one of America’s safest cities) across the border from Juarez, Mexico (one of the world’s most dangerous) if a wall works.”

Ask El Paso, Texas (now one of America's safest cities) across the border from Juarez, Mexico (one of the world's most dangerous) if a wall works https://t.co/UJCLNeuz4Y

— Kayleigh McEnany 45 Archived (@PressSec45) January 16, 2018

Sanders’ tweet linked to a Jan. 13, 2018, opinion piece in the New York Post from a conservative author under the headline, “This town is proof that Trump’s wall can work.” That article includes a series of cherry-picked crime statistics to prop up its flawed conclusion that construction of the border fence starting in 2008 has “dramatically curtailed … crime in Texas’ sixth-largest city … helping El Paso become one of the safest large cities in America.”

According to the author, Paul Sperry, “Before 2010, federal data show the border city was mired in violent crime. … Once the fence went up, however, things changed almost overnight. El Paso since then has consistently topped rankings for cities of 500,000 residents or more with low crime rates, based on FBI-collected statistics.”

In fact, El Paso was not “mired in crime” prior to 2010. It was already one of the safest large cities in America even before the fence. Among 35 U.S. cities with a population over 500,000 in the years 2005, 2006 and 2007 — before construction of the fence — El Paso had the third lowest violent crime rate (behind only San Jose and Honolulu). In 2010 — post-fence-construction — it slipped one spot to the fourth lowest violent crime rate, and stayed in that spot in 2011 and 2012.

Sperry, a former Hoover Institution media fellow, further cherry-picked FBI crime data to “[illustrate] just how remarkable the turnaround in crime has been since the fence was built.” Writes Sperry, “According to FBI tables, property crimes in El Paso have plunged more than 37 percent to 12,357 from their pre-fence peak of 19,702 a year, while violent crimes have dropped more than 6 percent to 2,682 from a peak of 2,861 a year.”

For property crime, Sperry is comparing the 37 percent drop in the raw number of property crimes from 19,702 in 2008 to 12,357 in 2016 (during a time when property crimes nationally were also in decline). But 2008 was not the “pre-fence peak.” In fact, the number of property crimes had been steadily declining from a high of 52,810 in 1990.

As for violent crimes, Sperry compares the 2,861 violent crimes committed in 2010 — post-fence — to the 2,682 in 2016. That is indeed a 6 percent drop. More notably, however, the number of violent crimes in El Paso was lower in 2005, 2006 and 2007 — all pre-fence years — than the number of violent crimes committed in 2010, 2011 and 2012 — all post-fence years.

According to Congressional Quarterly’s yearly 2008 City Crime Rankings, El Paso ranked 254th (out of 385) with a composite crime score below the national rate. New Orleans ranked first — meaning most dangerous — with a score of 441.40, while El Paso had a composite score of just 11.73. The ranking was based on the FBI’s data for murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary and motor vehicle theft in 2007. That was the year before construction of the fence began.

El Paso actually climbed the rankings — translation: not good — in the years immediately after the fence was completed in mid-2009. In CQ’s 2011 ranking (based on 2010 data), El Paso ranked 124th. The city’s ranking was 155th and 148th the two years after that. So much for the fence transforming the city “overnight” from one of the most dangerous to the safest.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: