Summary

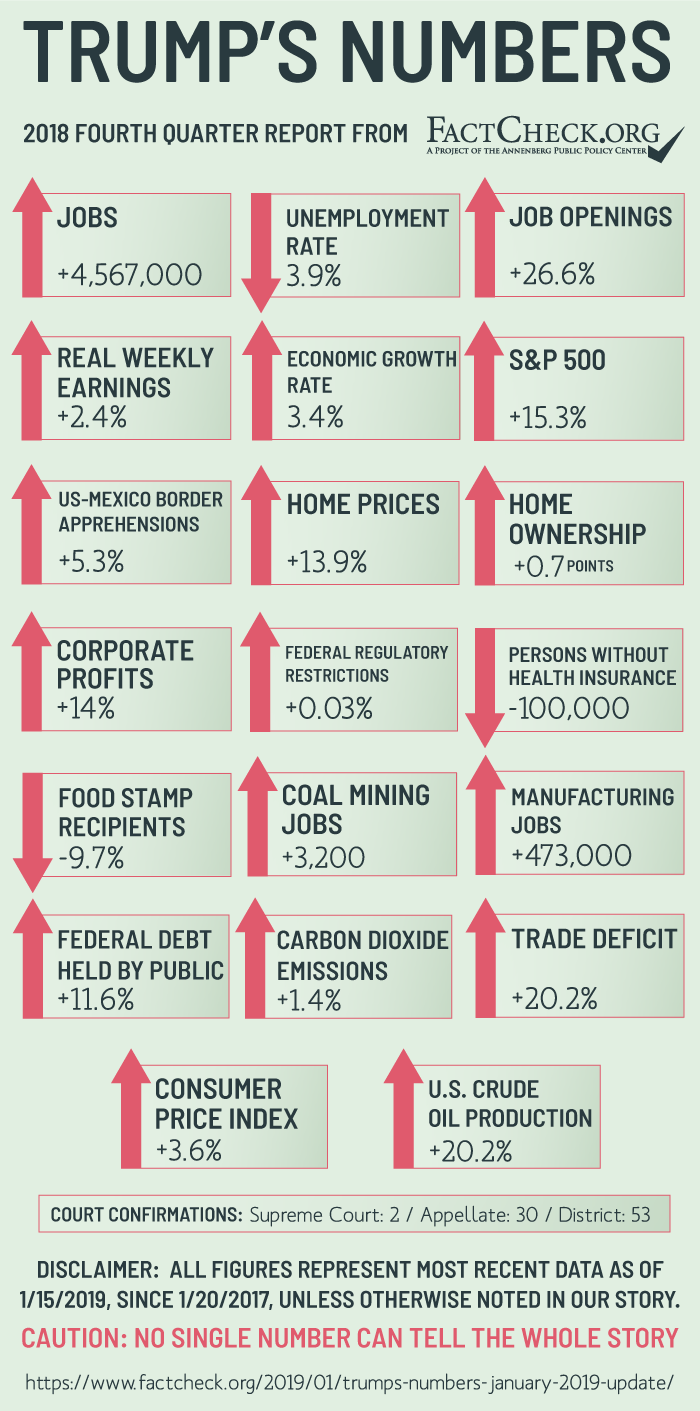

In the time Donald Trump has been in the White House:

- The economy added 4.6 million jobs, including nearly half a million in manufacturing.

- Economic growth quickened, but not as much as Trump promised.

- The number of regulatory restrictions stopped growing.

- Carbon dioxide emissions stopped falling, and have increased 1.4 percent under Trump.

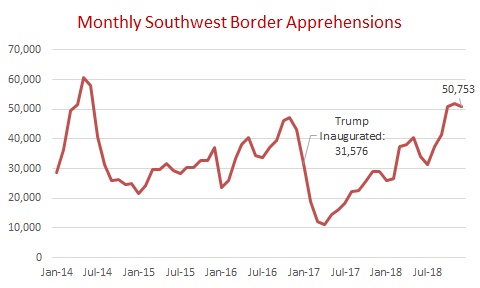

- Illegal border crossings have gone up.

- Only 22,774 refugees resettled in the U.S. last year — down 76 percent from 2016.

- The trade deficit increased 20 percent.

- The federal debt rose by $1.7 trillion; annual deficits accelerated.

- After-tax corporate profits soared to the highest on record.

Analysis

This is our fourth quarterly update of the “Trump’s Numbers” scorecard that we posted in January 2018 and updated on April 16, July 11 and Oct. 12. We’ll publish additional updates every three months, as fresh statistics become available.

As always, starting when we posted our first “Obama’s Numbers” article more than six years ago — and in the quarterly updates and final summary that followed — we’ve included statistics that may seem good or bad or just neutral, depending on the reader’s point of view.

We make no judgment as to how much credit or blame any president deserves for things that happen during his time in office. Opinions differ on that.

Jobs and Unemployment

Job growth slowed a bit under Trump, but unemployment dropped to the lowest point in nearly half a century.

Employment — Total nonfarm employment grew by nearly 4.6 million during the president’s first 23 months in office, according to the most recent figures available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

That continued an unbroken chain of monthly gains in total employment that started eight years earlier, in October 2010.

December saw an unusually large gain of 312,000, bringing the average monthly gain under Trump to 199,000. But that’s still less than the average monthly gain of 217,000 during Obama’s second term.

Trump will have to pick up the pace even more if he is to fulfill his campaign boast that he will be “the greatest jobs president that God ever created.”

Unemployment — The unemployment rate, which was well below the historical norm when Trump took office, has continued to fall even lower.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics now figures the rate was 4.7 percent when he was sworn in. Newly revised seasonal adjustment factors introduced this month put the rate even lower than the 4.8 percent BLS had been reporting. The most recent rate, for December, is 3.9 percent.

And it had been down to 3.7 percent earlier in 2018. That was the lowest since December 1969.

The historical norm is 5.6 percent, which is the median monthly rate for all the months since the start of 1948.

Job Openings — Another reason employment growth has slowed is a worsening shortage of qualified workers.

The number of unfilled job openings hit a new record of nearly 7.3 million as of the last business day in August — which was the most in the 18 years the Bureau of Labor Statistics has been tracking this figure. It has declined a bit since then, but openings still numbered nearly 6.9 million as of the last day in November, the most recent figure available.

That’s a gain of 1.4 million unfilled job openings — or 26.6 percent — since Trump took office. The number of job openings has exceeded the number of unemployed people looking for work since March of last year.

Labor Force Participation — Despite the abundance of jobs, the labor force participation rate — which went down 2.8 percentage points during the Obama years — has remained little changed under Trump.

The labor force participation rate is the portion of the entire civilian population age 16 and older that is either employed or currently looking for work in the last four weeks. Republicans often criticized Obama for the decline during his time, even though it was due mostly to the post-World War II baby boomers reaching retirement age, and other demographic factors beyond the control of any president.

Since Trump took office, the rate has fluctuated in a narrow range between 63.1 percent and 62.7 percent. It was 63.1 percent in December — up 0.2 percentage points from where it was the month Trump took office.

Manufacturing Jobs — Manufacturing jobs increased under Trump, even faster than total employment.

The number rose by 473,000 between Trump’s inauguration and December. That followed a net decrease of 192,000 under Obama.

The increase since January 2017 amounts to 3.8 percent, compared with the 3.1 percent increase in overall employment. The number of manufacturing jobs is still 904,000 below where it was in December 2007, at the start of the Great Recession.

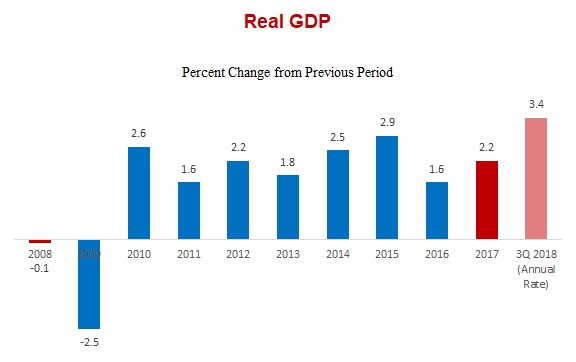

Economic Growth

The economy grew somewhat faster under Trump — but not at the rate he promised. It rose at a yearly rate of 3.4 percent in the third quarter of 2018, the most recent official estimate available.

Growth under Trump has averaged far less than the 4 percent to 6 percent per year that he promised repeatedly, both when he was a candidate and also as president.

The economy grew only 2.2 percent during his first year, and continued at a 2.2 percent yearly rate in the first quarter of 2018, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. As we reported in our last update, it then spurted to a 4.2 percent annual rate in the second quarter of 2018. Trump proudly claimed credit. But it then fell back to a 3.4 percent rate in the third quarter.

And it looks as though the economy slowed even further in the last quarter of 2018. The first official estimate from the BEA isn’t scheduled to be released until Jan. 30. However, the “GDPNow” forecast produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta projects that the fourth-quarter growth rate will come in at 2.8 percent.

Most economists believe the current growth spurt is temporary. The most recent median forecast of the Federal Reserve Board members and Federal Reserve Bank presidents issued on Dec. 19 projected 3.0 percent growth for all of 2018, 2.3 percent in 2019 and 2.0 percent in 2020. Similarly, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office issued an updated economic forecast Aug. 13 projecting real gross domestic product to grow 3.1 percent for all of 2018, falling to 2.4 percent this year and 1.7 percent next year.

Other leading economists tend to agree. For the business and university economists who offered an annual GDP forecast to the Wall Street Journal’s monthly economic survey in January, the average prediction was for 3.0 percent growth for all of 2018, falling to 2.2 percent this year and 1.7 percent next year. Similarly, the National Association for Business Economics’ December survey produced a median forecast of 2.9 percent growth for 2018 and 2.7 percent in 2019.

Regulations

The growth of federal regulation has come to a stop under Trump.

It wasn’t exactly the “sudden, screeching and beautiful halt” Trump prematurely claimed back in December 2017, when in fact the number of federal restrictions was still growing. But over the next several months the rise decelerated, and then reversed. The number of restrictions has now dropped to just about where it was when Trump was sworn in.

The number of restrictive words and phrases (such as “shall,” “prohibited” or “may not”) contained in the Code of Federal Regulations went up by 0.73 percent during Trump’s first 15 months, reaching a peak of nearly 1.09 million on April 6, 2018, according to daily tracking done by the QuantGov project at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center.

But as of Dec. 22, 2018, the most recent date for which Mercatus has posted a daily count, the number had dropped to 1,079,926 — which is just 325 more than on Jan. 20, 2017, the day Trump took office.

Hovering near zero growth is a big change from the past. Restrictions grew at an average of 1.5 percent per year during both the Obama years and the George W. Bush years, according to annual QuantGov tracking.

The Mercatus count of restrictions doesn’t attempt to assess the cost or benefit of any particular rule — such assessments require a degree of guesswork and are sensitive to assumptions. But it does track the sheer volume of federal rules with more precision than we have found in other metrics.

Some of the recent changes are cosmetic. Since our last report, the Treasury Department scrapped an entire chapter of zombie-like regulations issued by the old Office of Thrift Supervision, which oversaw the savings-and-loan industry before being abolished in 2011. S&Ls have since fallen under other federal banking regulators, but the obsolete OTS rules remained on the books.

However, many of the rules Trump has eliminated are quite significant. Within a month of taking office, for example, Trump signed a law nullifying an Obama-era rule prohibiting coal mining companies from dumping waste into streams and waterways. Last year his administration withdrew Obama’s edict requiring automakers to double the fuel efficiency of new cars and light trucks to 54.5 miles per gallon by the year 2025. Instead, the requirement will be capped at 37 mpg starting in 2020. And in May, Trump signed a massive rollback of banking regulations, easing rules for all but the largest banks.

Crime

Crime declined a bit in Trump’s first year, and seems to have gone down again in 2018, at least in the nation’s largest cities.

The number of homicides throughout the U.S. declined by 0.7 percent in 2017, according to the FBI’s annual Crime in the United States report, after rising for the previous two years. The number of all violent crimes went down by 0.2 percent, and the number of property crimes went down 3 percent.

Early data suggests that crime rates declined further in 2018. The Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law projects that the 2018 murder rate in the 30 largest U.S. cities will decline again, by nearly 6 percent, and the rate of all violent crime in 22 of those 30 cities will fall by 2.7 percent. Nationwide FBI figures for 2018 won’t be released until later this year, likely in September.

As a candidate, Trump repeatedly and falsely claimed that the murder rate was “the highest it’s been in 45 years.” In fact, the murder rate had dropped to the lowest on record in 2014 — 4.4 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. And while it did rise for the next two years, it was still only 5.4 per 100,000 in 2016, far below the peak rate of 10.2 reached in 1980.

Coal and Environment

Coal Mining Jobs — As a candidate, Trump promised to “put our [coal] miners back to work,” but so far not many have regained their jobs.

A total of 35,700 coal mining jobs disappeared during the Obama years, but as of December, only 3,200 of them had come back since Trump took office, according to BLS figures. That’s 9 percent of the coal mining jobs lost during the Obama years.

The outlook for coal miners remains bleak. The Energy Information Administration currently estimates that U.S. coal production will fall 3 percent this year, and by another 7 percent in 2020. EIA expects natural gas will continue to displace coal for the generation of electricity.

Carbon Emissions — Carbon dioxide emissions from energy consumption are now going up under Trump, after falling for years under Obama.

Figures from the Energy Information Administration show CO2 emissions fell by a total of 14.3 percent between 2007 and 2017, due mainly to electric utilities shifting away from coal-fired plants in favor of cheaper, cleaner natural gas, as well as solar and wind power.

After Trump took office CO2 emissions fell more slowly at first — by 0.8 percent in 2017, half the 1.7 percent decline in Obama’s final year. And the trend has now reversed entirely. Emissions during the most recent 12 months on record, ending in September 2018, were 1.4 percent higher than in all of 2016.

EIA estimated on Jan. 15 that CO2 emissions increased by 2.8 percent for all of 2018, compared with 2017. Earlier, the Rhodium Group, a private research firm, grabbed headlines with a “preliminary” estimate that the 2018 increase would be 3.4 percent.

Whatever the actual figure turns out to be, EIA said the 2018 rise is due mainly to a hotter summer and colder winter that resulted in higher natural gas consumption. It predicted that CO2 emissions would fall by 1.2 percent in 2019 and 0.8 percent in 2020, if temperatures return to normal as forecast.

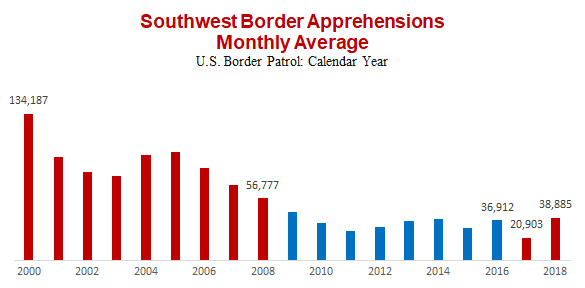

Border Security

Illegal border crossings, which at first declined under Trump, have now risen to above where they were the year before he took office.

The number of people caught while illegally trying to cross the U.S. border with Mexico each month plunged to a low of 11,127 in April of Trump’s first year, according to figures released by the U.S. Border Patrol. But since then, the number has more than quadrupled, hitting 51,856 in November and 50,753 in December.

For 2018, the monthly average was 38,885, which is 5.3 percent higher than the monthly average of 36,912 in 2016.

Looking in more detail at the recent rise — which Trump calls a “crisis” — we see a strong upward trend since April 2017. By this measure, apprehensions were 61 percent higher in December than in January 2017, when Trump took office. But we use a rolling monthly average for our comparisons because these monthly figures are subject to wide seasonal variations, or what former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh C. Johnson called “the seasonal uptick” in the spring months and a drop off at the beginning of the year.

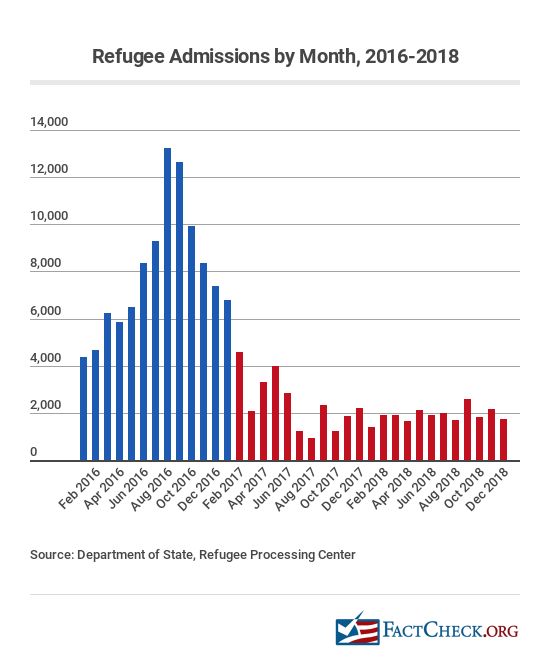

Refugees

The U.S. took in far fewer refugees under Trump.

U.S. State Department figures show only 22,874 refugees were resettled in the U.S. last year, down from 96,874 in 2016. That’s a decrease of 76 percent.

As a candidate, Trump at first called for a complete ban on all Muslims entering the U.S., but later called instead for “extreme vetting” of immigrants seeking admission.

As president, Trump issued an executive order on March 6, 2017, setting a ceiling of 50,000 for refugee admissions in fiscal year 2017, down from the 110,000 that President Obama had set for that year. He also suspended refugee admissions for 120 days, ending Oct. 24, 2017. And he cut the ceiling on refugee admissions even further for fiscal year 2018, to 45,000. On Sept. 24 last year, he cut the ceiling again, to 30,000, for the current fiscal year. Actual admissions have been running even below Trump’s ceilings, however.

Corporate Profits

After-tax corporate profits are running at record levels under Trump. During the third quarter of 2018, they hit an annual rate of $1.98 trillion. That, and the previous quarter’s figure of $1.96 trillion, are the two best quarters ever recorded.

The current quarterly rate is 14 percent higher than the full year figure for 2016, the year before Trump took office. It is also 6.7 percent above the best full-year figure ever previously recorded, which was $1.86 trillion in 2014.

These annual and quarterly estimates originate with the Bureau of Economic Analysis (see line 45).

After-tax profits got a boost in 2018 from the tax cut Trump signed into law Dec. 22, 2017, dropping the top federal tax rate on corporate income to 21 percent, from 35 percent.

Stock Market

Stock prices continued their long rise with Trump in office, setting record after record — only to see much of the gain erased in the final months of 2018, which ended with the worst December since 1931.

At the close on Jan. 15 the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock average had tumbled nearly 11 percent from the record high set on Sept. 20. But it was still 15.3 percent higher than it was on the last trading day before Trump’s inauguration.

Other indexes also saw recent declines, but still hung onto part of what they had gained in Trump’s first year. At the Jan. 15 close, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, made up of 30 large corporations, was up 22 percent under Trump. And the NASDAQ composite index, made up of more than 3,000 companies, was 26.8 percent higher than before Trump took office.

The bull market that began in 2009, at the depths of the Great Recession, passed its ninth anniversary in March, and on Aug. 22 was widely proclaimed to be the longest-running bull market in modern financial history. But by the end of the year some market watchers were proclaiming that a bear market was underway.

Wages and Inflation

The upward trend in real wages continued under Trump, and inflation remained in check.

CPI — The Consumer Price Index rose 3.6 percent during Trump’s first 23 months, continuing a long period of historically low inflation.

In the most recent 12 months, ending in December, the CPI rose 1.9 percent. The CPI rose an average of 1.8 percent each year of the Obama presidency (measured as the 12-month change ending each January), and an average of 2.4 percent during each of George W. Bush’s years.

Wages — Paychecks continued to grow faster than prices.

The average weekly earnings of all private-sector workers, in “real” (inflation-adjusted) terms, rose 2.4 percent during Trump’s first 23 months, after going up 3.9 percent during the previous four years.

Those figures are for all private-sector workers, including managers and supervisors.

For rank-and-file production and nonsupervisory workers (who make up 82 percent of all private-sector workers), real weekly earnings have gone up 2.5 percent so far under Trump, after rising 4.7 percent during Obama’s last four years in office.

Consumer Sentiment

Consumer confidence in the economy rose under Trump, but has slipped a bit since our last update.

The University of Michigan’s Surveys of Consumers reported that its Index of Consumer Sentiment hit 101.4 in March of last year, which was the highest in more than two decades. But from there it slid to 98.3 in December.

That’s 0.2 lower than it was in the month Trump took office, but still a favorable level. For all of 2018 the level averaged 98.4, which was the best full-year average since 2000.

However, the December survey picked up some emerging worries. The survey’s chief economist, Richard Curtin, said: “Consumers reported more negative than positive news about job prospects for the first time in two years, with the shift widespread across socioeconomic subgroups.”

Home Prices and Ownership

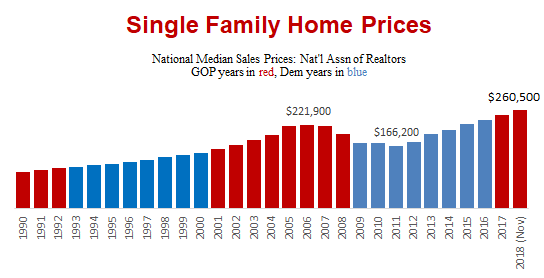

Home Prices — Home prices soared to record levels under Trump, but recently have slipped back a bit.

The most recent sales figures from the National Association of Realtors show the national median price of an existing, single-family home sold in November was $260,500. Earlier, in June, the average price hit $276,500 — the highest ever recorded — but prices fell back in subsequent months.

The November average is still $31,800 higher than the median price of $228,700 for homes sold during the month Trump took office — a gain in value of 13.9 percent. The rise in the Consumer Price Index during the same period was 3.6 percent.

The Realtors figures reflect raw sales prices without attempting to adjust for such factors as variations in the size, location, age or condition of the homes sold in a given month or year. Even so, a similar pattern emerges from the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index, which compares sales prices of similar homes and seeks to measure changes in the total value of all existing single-family housing stock.

The Case-Shiller index for October sales (the most recent available) was a record high, and was 11.5 percent higher than where it stood in the month Trump took office.

Whichever way you measure it, homeowners have seen the value of their houses rise substantially since Trump took office.

Homeownership — Meanwhile, the percentage of Americans who own their homes has continued to recover from a years-long slide, gaining 0.7 percentage points since Trump took office.

The homeownership rate began to slide after peaking at 69.2 percent of households for two quarters in 2004. It hit bottom in the second quarter of 2016 at 62.9 percent — the lowest point in more than half a century, and tied for the lowest on record.

The rate recovered 0.8 points before Trump took office, and has gone up another 0.7 points since then, reaching 64.4 percent in the third quarter of 2018, according to the most recent Census Bureau figures.

Not all Americans have benefited from the rise in homeownership. The homeownership rate for black households was 41.7 percent in the third quarter — the same as it was at the end of 2016 and near a 50-year low, according to the National Association of Real Estate Brokers.

Trade

The trade deficit that Trump promised to reduce grew larger instead.

The most recent government figures show that the total U.S. trade deficit in goods and services during the most recent 12 months on record, ending in October, was $604 billion. That’s an increase of $102 billion, or 20.2 percent, compared with 2016.

China — The goods-and-services trade deficit with China grew at a similar clip, up by 18 percent between 2016 and the most recent 12 months on record, ending in October, when it hit nearly $364 billion.

Trump last year initiated a full-scale trade conflict with China, imposing tariffs on $250 billion worth of Chinese goods. China has retaliated with its own tariffs on $110 billion in U.S. goods. Trump tweeted Jan. 8 that talks to strike a new trade deal with China are going “very well,” but so far little progress has been made.

Mexico — Meanwhile, the much smaller trade deficit in goods and services with Mexico totaled $75 billion during the 12 months ending in October, an increase of 20.3 percent compared with 2016.

Canada — The trade surplus that the U.S. runs with Canada has practically disappeared under Trump. The trade balance was positive by less than $1 billion during the 12 months ending in October. That surplus is 86.9 percent smaller than it was in 2016. For the most recent quarter, ending Sept. 30, the U.S. actually ran a $2.7 billion trade deficit with Canada.

On Nov. 30 Trump and the leaders of Canada and Mexico signed a new trade agreement to replace the 25-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement, which Trump had promised to scrap during his campaign. The new agreement will be called the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA. The new agreement still requires approval by Congress before it can take effect. Democrats took control of the House this month, and Speaker Nancy Pelosi has cast doubt on whether the new deal can gain approval without changes to some of its provisions.

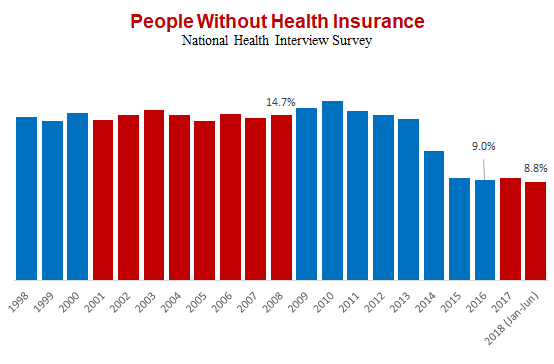

Health Insurance Coverage

The number of people lacking health insurance has barely changed since Trump took office, but millions are expected to drop or lose coverage this year, and in subsequent years.

The most recent report from the National Health Interview Survey estimates that 28.5 million people were uninsured during the first six months of 2018, about 100,000 fewer than in 2016. Only 8.8 percent of the population lacked health coverage during that time, down from 9.0 percent during Obama’s last year.

That’s a reversal of the trend in Trump’s first year, when the number who lacked coverage rose by 700,000, according to the NHIC.

Trump failed to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act as he promised to do. But in December 2017 he signed a tax bill that will end the ACA’s tax penalty for people who fail to obtain coverage.

That took effect this year. Earlier, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that the end of the mandate penalty will cause 4 million people to lose or drop coverage this year, rising to 12 million two years later and 13 million in 2025.

Food Stamps

The number of food stamp recipients went down since Trump’s inauguration.

As of September, the most recent month for which figures are available, 38.6 million people were receiving the aid, the lowest number since November 2009. The number has gone down 4.1 million, or 9.7 percent, since January 2017, when Trump took office.

The number generally has been going down since peaking at nearly 47.8 million in December 2012, as the economy recovered from the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

In December, the Trump administration issued a proposed rule that would tighten work requirements for able-bodied adults between the ages of 18 and 49, with no dependents. Generally, the rules limit aid to three months for such adults, but many states secured waivers to that rule during the 2007-2009 recession and still have them in place, despite a booming economy. Trump’s proposal would affect only a small fraction of all food stamp recipients, however. Less than 9 percent of all people getting food stamps are classified as able-bodied adults living in households without children, and 26 percent of those are already working, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Judiciary Appointments

Trump is putting his mark on the federal courts — from top to bottom — more quickly than Obama was able to do in his first two years.

Supreme Court — So far Trump has won Senate confirmation for two Supreme Court nominees, Justice Neil Gorsuch and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh.

Obama also was able to fill two high court vacancies during his first two years in office, with Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Justice Elena Kagan. But the Kavanaugh nomination to fill the vacancy created by Justice Anthony Kennedy’s retirement is significant because Kavanaugh may move the court to the right. He is considered more conservative than Kennedy, who sometimes sided with the liberal justices to provide deciding votes on issues including gay rights, abortion, capital punishment and affirmative action.

However, Kavanaugh disappointed abortion foes when he sided with the court’s liberals on one of his first votes, against taking up a case about whether citizens should be allowed to sue states that cut off Medicaid funding for Planned Parenthood health clinics.

Court of Appeals — Trump also won confirmation for 30 U.S. Court of Appeals judges during his first two years. (So far, no judges have been confirmed by the current Congress, which was seated this month.) Trump’s total compares with only 16 for Obama at the same point in his first term.

District Court — Trump also has won confirmation for 53 of his nominees to be federal District Court judges, exceeding the 44 for whom Obama had won confirmation at the same point in his presidency.

Trump must share responsibility for this record with the Republican majority in the Senate. Republicans not only refused to consider Obama’s appointment of Merrick Garland to fill the Supreme Court vacancy eventually filled by Gorsuch, but they also blocked confirmation of dozens of Obama’s nominees to lower courts. Trump inherited 17 Court of Appeals vacancies, for example, including seven that had Obama nominees pending but never confirmed.

Federal Debt and Deficits

Trump inherited rising federal debt and deficits, and his tax cut and spending increases are making both rise faster.

The federal debt held by the public stood at nearly $16.1 trillion at the last count on Jan. 14 — nearly $1.7 trillion higher than when he took office. That’s an 11.6 percent increase under Trump. And that figure will go up even more quickly in coming years unless Trump and Congress impose massive spending cuts, or reverse course and increase taxes.

Trump’s cuts in corporate and individual income tax rates — as well as the bipartisan spending deal he signed Feb. 9 — are causing the red ink to gush even faster than it did before. The annual federal deficit for fiscal year 2018, which ended Sept. 30, was $779 billion, up from nearly $666 billion the year before.

That’s an increase of $113 billion. Much of the increase was due to reduced receipts from corporate income taxes, which fell by $92 billion.

CBO estimates that the deficit will continue rising for the foreseeable future, exceeding $1 trillion annually starting in fiscal year 2020. (Baseline deficit projections are in Table 1, page 2.) Further, CBO said on June 26 that under current law, federal deficits will continue growing for the next 30 years, “reaching the highest level of debt relative to GDP in the nation’s history by far.” CBO projected that under current law, debt would reach 152 percent of the nation’s total annual economic output by 2048 — up from 78 percent currently.

Oil Production and Imports

U.S. crude oil production resumed its upward trend under Trump, rising 20.2 percent during the most recent 12 months on record (ending in October), compared with all of 2016.

Domestic oil production has increased every year since 2008, except for a 6.1 percent drop in 2016 after prices plunged to below $30 a barrel, from more than $100 in 2014. The price returned to more than $50 a barrel by the end of 2016 and has hovered around $70 for many weeks, prompting increased drilling and production.

As a result, the trend to reduce reliance on foreign oil also resumed. The U.S. imported only 12.8 percent of its oil and petroleum products during the first 11 months of 2018, down by nearly half from 24.4 percent in all of 2016.

Dependence on imports peaked in 2005, when the U.S. imported 60.3 percent of its petroleum, and it has declined every year since except for 2016, when it ticked up by 0.3 percentage points.

Sources

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National); Total Nonfarm Employment, Seasonally Adjusted.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; Unemployment Rate, Seasonally Adjusted.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey: Job Openings, Seasonally Adjusted.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; Labor Force Participation Rate.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; All employees, thousands, manufacturing, seasonally adjusted.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Gross Domestic Product, 3rd quarter 2018 (third estimate).” 21 Dec 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Table 1.1.1. Percent Change From Preceding Period in Real Gross Domestic Product.” Interactive data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

Wall Street Journal. “WSJ Economic Survey January 2019.”

National Association of Business Economists. “NABE Outlook Survey – December 2018.”

McLaughlin, Patrick A., and Oliver Sherouse. RegData US 3.0 Daily (dataset). QuantGov, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA. Daily Summary tracking of restrictions in the eCFR (Electronic Code of Federal Regulations). Downloaded 15 Jan 2018.

McLaughlin, Patrick A. and Oliver Sherouse. 2017. “QuantGov—A Policy Analytics Platform.” “RegData 3.0 Restrictions by Year.” Downloaded 15 Jan 2018.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. “Crime in the United States 2017;” Table 1. 24 Sep 2018.

Grawert, Ames and Cameron Kimble. “Crime in 2018: Updated Analysis.” Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law. 19 Dec 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; All employees, thousands, coal mining, seasonally adjusted.” Data extracted. 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. Short Term Energy Outlook. 15 Jan 2019.

U.S. Border Patrol. “U.S. Border Patrol Apprehensions FY2019” Undated. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “DHS Releases Southwest Border Enforcement Statistics.” News release. 9 Jan 2019.

U.S. Border Patrol. “Total Illegal Alien Apprehensions By Month Fiscal Years 2000-2017.” Undated. Accessed 15 Jan 2019.

U.S. Department of State. Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. “Refugee Arrivals From January 1, 2018 through December 31, 2018,” report created using interactive data from Refugee Processing Center. 15 Jan 2019.

U.S. Department of State. Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. “Refugee Arrivals From January 1, 2016 through December 31, 2016,” report created using interactive data from Refugee Processing Center. 15 Jan 2019.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Corporate Profits After Tax (without IVA and CCAdj) [CP], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 15 Jan 2018.

Yahoo! Finance. “Dow Jones Industrial Average.” Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Yahoo! Finance. “S&P 500.” Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Yahoo! Finance. “NASDAQ Composite.” Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Franck, Thomas. “On the bull market’s ninth birthday, here’s how it stacks up against history.” CNBC.com. 8 Mar 2018.

Eagan, Matt. “Market milestone: This is the longest bull run in history.” CNN.com. 22 Aug 2018.

Suttmeier, Richard Henry. “Bear Market Rally Will Stall Or Accelerate Based On This Week’s Closes.” Forbes. 13 Jan 2019.

Rooney, Kate. “We are now in a bear market — here’s what that means” CNBC. 24 Dec 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Consumer Price Index – All Urban Consumers.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National); Average Weekly Earnings of All Employees, 1982-1984 Dollars.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National); Average Weekly Earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, 1982-1984 Dollars.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers. “The Index of Consumer Sentiment.” Dec 2018.

National Association of Realtors. “Sales Price of Existing Single-Family Homes.” 19 Dec 2018.

S&P Dow Jones Indices. “S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2019.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Time Series: Not Seasonally Adjusted Home Ownership Rate.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, October 2018.” 6 Dec 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Table 1, U.S. Trade in Goods and Services, 1992-present.” 6 Dec 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. ”Table 3. U.S. International Trade by Selected Countries and Areas: Balance on Goods and Services.” 6 Dec 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Health Interview Survey. “Health Insurance Coverage: Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, January – June 2018.“ 15 Nov 2018.

Congressional Budget Office. “Repealing the Individual Health Insurance Mandate: An Updated Estimate.” 8 Nov 2017.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (Data as of Dec 7, 2018).” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) data, fiscal years 1968-2017.

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “Judicial Confirmations for January 2019,” archived web listing of confirmations in 115th Congress. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “Judicial Confirmations for February 2010,” archived web listing of confirmations in 110th Congress. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Treasury. “The Debt to the Penny and Who Holds It.” Data extracted 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Treasury. “Final Monthly Treasury Statement of Receipts and Outlays of the United States Government For Fiscal Year 2017 Through September 30, 2017.” 20 Oct 2017.

U.S. Treasury. “Final Monthly Treasury Statement of Receipts and Outlays of the United States Government For Fiscal Year 2018 Through September 30, 2018.” 15 Oct 2018.

Congressional Budget Office. “An Analysis of the President’s 2019 Budget.” 24 May 2018.

Congressional Budget Office. “The 2018 Long-Term Budget Outlook.” 26 Jun 2018.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “U.S. Field Production of Crude Oil.” Data accessed 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Weekly Cushing OK WTI Spot Price FOB.” Weekly oil price data. Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Table 3.3a Petroleum Trade: Overview.” Monthly Energy Review. 25 Sep 2018, Accessed 15 Jan 2018.