President Donald Trump misleadingly claimed that “deficits seem to be coming down,” when in fact deficits are rising, largely because of the tax cuts he enacted.

In fact, the deficit in the first three months of fiscal year 2019 was 42 percent higher than it was for the same period last year.

Trump’s comment came as the president boasted about the country’s strong economy during a signing ceremony for a space policy directive.

Trump, Feb. 19: I don’t know if you noticed, but deficits seem to be coming down. And last month it was reported, and everybody was surprised, but I wasn’t surprised. We’re taking in a lot of money coming into our Treasury from tariffs and various things, including the steel dumping. And our steel companies are doing really well. Aluminum companies also. So we’re very happy about that.

The White House press office did not respond to our request for clarification or backup data, but the president appeared to be referring to the latest monthly deficit tabulation released by the Treasury Department. In December, the U.S. government ran a relatively low deficit of $13.5 billion, Treasury announced this month. That’s nearly $10 billion less than the previous December.

But the total deficit for the first three months of the fiscal year, ending in December, was $319 billion. (See Table 1.) That’s 42 percent higher than in the first three months of FY 2018. (See Table 2.)

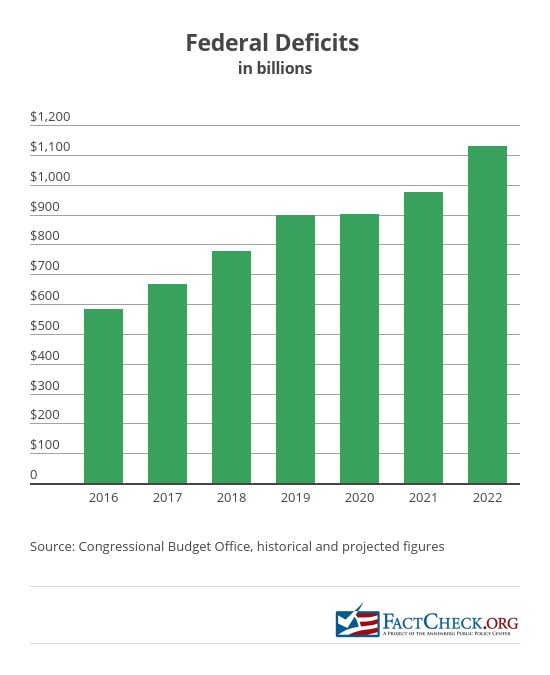

Even so, experts told us it is unwise to cherry-pick a single month or even several months, as federal revenue and spending often fluctuate cyclically at different times of the year. It is better to look at the longer-term, yearly deficits, and the trend line there is clear: Deficits have increased under Trump, and they are forecast to continue to go up, according to projections by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

“December is almost always a relatively good month for the federal government,” Shai Akabas, director of economic policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, told us in a phone interview. Fewer federal payments go out the door, and so historically deficits in Decembers are usually relatively low. The federal government shutdown also skewed the government’s bottom line that month. The deficit for January, which Treasury has not yet released, is also likely to be relatively low, and may even be a surplus, he said. Quarterly tax payments due in January typically give revenues that month a large bump.

“Looking at one month and saying deficits are getting better is like looking at the weather in November and December and saying the climate is getting colder,” Akabas said.

December’s figure is not indicative of the long-term trend, he said. “Deficits are rising significantly.”

The federal deficit in FY 2018, which ended Sept. 30, was $779 billion — a nearly 17 percent increase from FY 2017. According to the Congressional Budget Office, about $164 billion of the 2018 deficit resulted from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — a Republican-crafted bill that the president signed into law on Dec. 22, 2017.

Revenue loss from the tax bill is expected to have an even larger impact on the deficit this year. According to the latest economic forecast from the Congressional Budget Office, released in January, the federal budget deficit is expected to reach nearly $900 billion this fiscal year (a 15 percent increase from 2018) and exceed “$1 trillion each year beginning in 2022.”

The White House, in its mid-session review of the fiscal year 2019 budget, estimates even larger short-term deficits than CBO. That document projects annual deficits will top $1 trillion in fiscal years 2019, 2020 and 2021.

“You can’t look at a single month to tell you much of anything” Marc Goldwein, senior vice president and senior policy director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, told us via email. “Overall, deficits are way up since the President took office.”

CRFB says the tax bill is the largest driver of increasing deficits, but increased spending, particularly on defense, also has played a role.

“The deficit is not going down,” Steve Ellis of the budget watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense told us via email. “It’s not very useful to look at the deficit from month to month or even the same month year to year. The last month had some saving because of the government shutdown, but that is going to be more than made up going forward.”

The timing of payments and even variables such as the number of weekends in a month has an effect on monthly deficits, Ellis said.

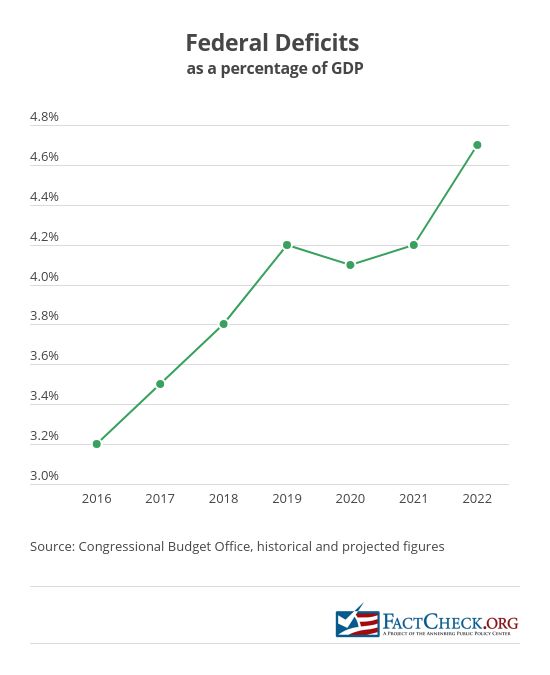

“The real measure of the deficit is as a percentage of GDP,” Ellis said. “Bottom line, since WWII the only other times the deficit has been this high was immediately after WWII and immediately after the Great Recession. But we have this level of deficits during an economic expansion, that’s unconscionable.”

According to the latest economic forecast from the Congressional Budget Office, “Over the coming decade, deficits … [will] fluctuate between 4.1 percent and 4.7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), well above the average over the past 50 years,” and will average 4.4 percent a year from 2020 to 2029.

By comparison, CBO said: “Over the past 50 years, the annual deficit has averaged 2.9 percent of GDP.

The Trump administration contests the CBO projection. In a press briefing on Jan. 28, Larry Kudlow, director of the White House National Economic Council, said the White House simply disagrees with CBO about projected economic growth and, in turn, its deficit projections.

Kudlow, Jan. 28: So they [CBO] have had a very low growth estimate in response to Trump policies on taxes and deregulation, and we’ve had a much higher one — about a 1-percentage point differential, more or less. We’re at 3; they’re at 2, more or less.

The White House budget for fiscal year 2019 assumed “real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth averaging 3.0 percent during the 11-year forecast interval,” from 2018 to 2028.

But few outside the White House share such a rosy view. The most recent median forecast of the Federal Reserve Board members and Federal Reserve Bank presidents issued on Dec. 19 projected 3.0 percent growth for all of 2018, 2.3 percent in 2019 and 2.0 percent in 2020. Similarly, among the business and university economists who offered an annual GDP forecast to the Wall Street Journal’s monthly economic survey in January, the average prediction was for 3.0 percent growth for all of 2018, falling to 2.2 percent this year and 1.7 percent next year.

Trump asserted that increased revenues from “tariffs and various things” are bringing down the deficit, but increased revenues from tariffs are dwarfed by revenue losses from the tax cuts.

In the first three months of this fiscal year, the federal government took in about $17.8 billion in “customs duties” — about $8.4 billion more than during the same three months last year, according to the Treasury (Table 7). CBO says that increase in customs duties was “largely because of new tariffs imposed by the Administration during the past year.” By contrast, however, the CBO forecasts revenue losses from the tax cuts of $228 billion this year, and $272 billion in FY 2020.

“Tariffs definitely bring in some revenue,” Akabas said. “But in the scheme of things, they are quite small, several billion dollars as opposed to deficits of several hundred billion dollars.”

The long-term, big picture on deficits is clear, Akabas said. Deficits are rising under Trump, and in the years ahead, “The CBO projects rising deficits with no end in sight.”

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: