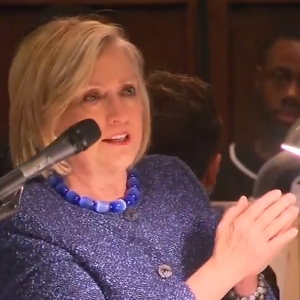

In remarks in Alabama, Hillary Clinton took aim at state laws that she said disenfranchise minority voters. But she went too far in a couple of instances when discussing the impact of Wisconsin and Georgia laws in the 2016 election, when she ran for president:

- Clinton said the “best studies” show that “somewhere between 40[000] and 80,000 people were turned away from the polls” in Wisconsin because of the state’s voter ID law. Her office provided us with reports that did not support the figures she cited, and we could find no credible statewide estimate.

- Clinton falsely claimed that “there were fewer voters registered in Georgia [in 2016] than then there had been those prior four years” in 2012. In fact, there were nearly 571,000 more registered voters in the 2016 election, state records show.

The former Democratic presidential nominee made her remarks on March 3 at the annual “Bloody Sunday” commemorative service, which was held at the Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma, Alabama.

In 2016, Clinton won the popular vote by a wide margin, but lost the Electoral College vote and the presidency to Donald Trump. She lost the popular vote by a combined 77,744 votes in three Rust-Belt states that President Barack Obama had won in 2008 and 2012 — Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — costing her 46 electoral votes and the election.

During her remarks in Selma, Clinton spoke about the impact of a 2013 Supreme Court decision that overturned a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. In part, the court ruled that it was unconstitutional to require some states to get federal approval of state laws that could disproportionately affect minority voters. Nine states, including Georgia, and parts of six others were subject to the so-called preclearance requirement at the time of the court ruling, according to the Department of Justice.

Wisconsin Voter ID

Clinton spoke about the impact that restrictive state voting laws had on voter registration and turnout in Wisconsin and Georgia in 2016.

Here’s what she said about Wisconsin, which was not subject to the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance requirement.

Clinton, March 3: I was the first person who ran for president without the protection of the Voting Rights Act and I will tell you, it makes a really big difference. And it doesn’t just make a difference in Alabama and Georgia. It made a difference in Wisconsin where the best studies that have been done said somewhere between 40[000] and 80,000 people were turned away from the polls because of the color of their skin, because of their age, because of whatever excuse could be made up to stop a fellow American citizen from voting.

We asked Clinton’s spokesman, Nick Merrill, for the studies that Clinton referenced in her remarks. But what he provided did not support her claim that “between 40[000] and 80,000 people were turned away from the polls” in Wisconsin because of the state’s voter ID law.

Merrill referred us to a Mother Jones story about a study done by the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where researchers surveyed nonvoters to estimate how many of them were deterred from voting by the voter ID law. But that study was limited to two counties, Milwaukee and Dane, and warned against using the study to extrapolate a statewide estimate.

The center mailed surveys to 2,400 people in Milwaukee and Dane counties who were registered and eligible to vote, but did not vote. A total of 293 nonvoters returned the survey. Based on those results, the center estimated that 11.2 percent, or 16,801, of eligible voters were deterred by the voter ID law. (The actual number could have been higher. The estimated number of deterred voters ranged from 11,701, or 7.8 percent, to 23,252, or 15.5 percent, the authors explain in a supporting document.)

The researchers pointedly and repeatedly said their work could not be used to derive a statewide estimate.

“The 11.2% figure cannot be directly extrapolated statewide, because we do not know how people outside of Dane or Milwaukee Counties would have answered the questions about their reasons for nonvoting or whether or not they possess a qualifying form of photo ID,” the study said. “The statewide totals outside of Dane and Milwaukee are certain to be greater than zero, but we cannot assume that the effect was the same, 11.2%.”

At another point, the study said: “These counties contain the two largest metro areas in the state (Milwaukee and Madison) and have the largest low-income and minority populations, which research has shown are most likely to be affected by voter ID requirements. For this reason, the estimates cannot be extrapolated to the state of Wisconsin as a whole.”

Nevertheless, Mother Jones attributed a statewide estimate of 45,000 voters to the lead author on the study, University of Wisconsin-Madison political science Professor Kenneth R. Mayer.

“Extrapolating statewide, he says the data suggests as many as 45,000 voters sat out the election, though he cautioned that it was difficult to produce an estimate from just two counties,” the Mother Jones story said of Mayer.

We sent three emails to Mayer and called his office over the course of three days, but he did not respond to our questions about his report or the Mother Jones article. However, he did tell the Washington Post Fact Checker that he was misinterpreted by the magazine. “That’s not a claim that I made,” Mayer told the Post.

Washington Post, March 6: “We were careful not to extrapolate statewide, as we do not have information about what the effects were outside of the regions we sampled,” Mayer wrote in an email. “Our goal was to understand the effects more precisely, among populations most likely to be affected. We also were careful, in that someone who did not vote because of the ID law might not have voted even if the law were not in effect.”

As for the 80,000 estimate, Clinton’s office referred us to an analysis of the 2016 presidential election results by the Tides Foundation and the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society. Merrill, Clinton’s spokesman, sent us an excerpt from the report about the decline in black turnout, and highlighted a sentence that mentions Wisconsin (in bold below).

Tides Foundation and Haas Institute, November 2017: Census Bureau figures on turnout raise questions about the impact of voter ID laws, early-voting cutbacks, and elimination of same-day voter registration on African American voting. These and other voter suppression techniques have been instituted in numerous states since 2012, including a handful of swing states. Among these are North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin — each of which lost 80,000 or more Black voters in 2016 according to the Census Bureau. It is difficult, however, to assess how much of this drop is due to the states’ new laws versus lack of enthusiasm for the candidates. One possible approach would be to begin by comparing African American turnout in neighboring states that have no such laws. But unfortunately, there are enormous discrepancies across data sources and methods for estimating Black voter turnout in Michigan in 2016, and smaller but still significant discrepancies for Pennsylvania.

But, as the excerpt above shows, the report did not give a reason why about 80,000 fewer black voters cast ballots in Wisconsin in 2016 compared with 2012. “It is difficult, however, to assess how much of this drop is due to the states’ new laws versus lack of enthusiasm for the candidates,” the report said.

The report also noted that there was a large number of voters, including those in Wisconsin, who cast ballots for third-party candidates. “In Wisconsin, where Trump’s margin was +0.8 points, ‘third party’ and write-in candidates garnered 5.56 percent of votes for president,” the report said.

In its conclusion, the report said: “Depressed turnout rates — and quite possibly voter suppression — across several Democratic-leaning groups contributed enormously to Clinton’s defeat.” However, it also said: “Those who wish to assign blame can — and do — debate whether the brunt should be placed on Obama voters who swung to Trump, Romney voters who didn’t swing to Clinton, or those who voted for neither major-party candidate. But a clear-eyed assessment must acknowledge that no one of these alone can be deemed the reason for the election’s outcome.”

Lastly, Clinton’s office cited a partisan analysis published by a Democratic-aligned super PAC, Priorities USA, that said Wisconsin’s voter ID law prevented as many as 200,000 voters from voting.

“While states with no change to voter identification laws witnessed an average increased turnout of +1.3% from 2012 to 2016, Wisconsin’s turnout (where voter ID laws changed to strict) dropped by -3.3%,” the Priorities USA report said. “If turnout had instead increased by the national-no-change average, we estimate that over 200,000 more voters would have voted in Wisconsin in 2016. For context, Clinton lost to Trump in Wisconsin by only 20,000 votes.”

But the Priorities USA report implies a causation that it cannot prove without conducting the research.

There is no doubt that the voter ID law deterred thousands of registered Wisconsin voters from casting ballots in the 2016 election. The University of Wisconsin-Madison study shows that. But we could find no credible statewide estimate that supports Clinton’s claim that “between 40[000] and 80,000 people were turned away from the polls” in Wisconsin in 2016.

“There is much debate about the numbers of voters who were deterred from voting in 2016, but no matter what study you’re looking at, even the most conservative efforts were enough to change the outcome in more than one key state,” Merrill said in an email to FactCheck.org. “Voter suppression is getting worse not better, and fighting for that basic right is critical going forward.”

Updated, March 7: We updated this story to include the above statement from Clinton’s spokesman, Nick Merrill.

Georgia Voter Registration

Clinton also claimed that as a result of a controversial state law in Georgia — a state that was previously covered by the Voting Rights Act — there were fewer people registered to vote in 2016 than in 2012.

Clinton, March 3: Between 2012, the prior presidential election, where we still had the Voting Rights Act, and 2016, when my name was on the ballot, there were fewer voters registered in Georgia than then there had been those prior four years. Think about it my friends.

We did think about it. We also went to the Georgia Secretary of State’s website for registration data, and we found that she was wrong.

There were 5,443,046 active voters and 1,194,893 inactive voters for a total of 6,637,939 registered voters in Georgia for the November general election in 2016, according to state historical data. That represented an increase of 90,033 active voters and 480,945 inactive voters for a total of 570,978 more total registered voters in 2016 compared with 2012.

John Hallman, Georgia’s election systems manager, told us that “inactive voters” are those who haven’t voted or made contact with the Elections Division of the Secretary of State’s office for three years. He said “inactive voters” are eligible to vote and, if they do, they are moved to active status. However, they are in danger of having their names removed from the voter rolls for future elections.

Georgia has one of the most restrictive state laws when it comes to what Hallman called voter registration “maintenance.” Critics call it voter suppression.

In a story on a U.S. Supreme Court ruling last year that upheld the state law, the Atlanta Journal Constitution explained how the state law works: “In Georgia, registered voters who fail to vote for three years and then don’t respond to a letter from the state are moved to ‘inactive status.’ Inactive voters can still participate in elections. Voters who remain inactive for two federal election cycles without voting or having any other contact with election officials are removed from voter rolls.”

Hallman said it usually takes five years to move an inactive voter to what he called “cancelled status.” But, he said, that didn’t happen in 2016, when there were 1,194,893 inactive voters — far more than the 713,948 inactive voters in 2012. He said the state ran out of time before it could complete the “maintenance” process in 2016.

For purposes of calculating voter participation, the state uses “active voters” as the baseline. But it doesn’t matter which designation we use to look at registered voters: The numbers of both active and inactive voters went up in 2016.

Clinton was wrong when she said “there were fewer voters registered in Georgia [in 2016] than then there had been those prior four years” in 2012.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: