In a recent town hall, Iowa Rep. Steve King focused on the positives of climate change, inaccurately stating that increased evaporation under higher temperatures will lead to rain in “more and more places” — a result that’s “surely gotta shrink the deserts and expand the green growth.”

Part of what King says is true — warmer temperatures will increase evaporation — but rainfall is expected to be uneven, growing in some places, and lessening in others. Climate models tend to project precipitation increases in areas where it already rains or snows, while decreases are projected in drier regions.

King made his comments in a town hall in Cherokee, Iowa, on April 23 in response to a woman’s question about geoengineering (at about the 25:30 mark in the video).

King made his comments in a town hall in Cherokee, Iowa, on April 23 in response to a woman’s question about geoengineering (at about the 25:30 mark in the video).

“You didn’t mention the global warming part of this, other than the weather patterns that are there,” King said. “But I think that, I began, when I first looked at that, I thought, ‘I’m hearing all these things that are bad. Well, what could be good?’ Surely on the other side there is something good.”

He went on to give the example of being able to measure the amount of water evaporating from a barrel in Iowa in July, before launching into how precipitation changes would provide benefits:

King, April 23: Seventy percent of the earth is covered by water. If the earth warms, then there will be more evaporation that goes into the atmosphere. According to Newton’s First Law of Physics, what goes up must come down.

That means it will rain more and more places. It might rain harder in some places, it might snow in some of those places. But it’s surely gotta shrink the deserts and expand the green growth, there’s got to be some good in that. So I just look at the other, good side.

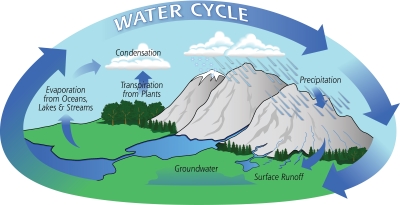

King’s explanation starts off fairly well — under increased temperatures, there will be more evaporation, and he’s mostly right that the water that goes up will come back down. But that’s not because of a law of physics, and certainly not Newton’s first law of inertia, which states that an object will remain at rest or continue moving unless another force acts upon it. It’s because of the water cycle.

We reached out to King’s office to ask for support for his statements, but did not receive a reply.

We’ll go into more detail about why King’s conclusions about rainfall aren’t accurate, and why he might be correct that green growth will expand — but not, as he thinks, because of increased precipitation.

Rain ‘More and More Places’?

King’s central argument is that as temperatures rise, evaporation will increase, resulting in rain “more and more places.”

As multiple experts explained, King is partly right — evaporation will increase, and models predict there will be slightly more rain, on average, across the globe. But that’s only the average. It doesn’t account for the kind of precipitation events or where they occur.

“It’s not true it’s going to rain more everywhere,” said Jack Scheff, an atmospheric scientist at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, in a phone interview.

It will rain more in some places, he said, but less in others, and some may not change much at all. Or, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s fifth assessment report put it, “Changes in precipitation will not be uniform.”

With global warming, precipitation changes are more difficult to assess than temperature. So, scientists are less certain about them, and different climate models disagree about what will happen for much of the globe. But for the places on which the majority of the models do agree, it’s typically drier spots that are projected to see drops in precipitation, while the bumps happen in wetter areas.

“The high latitudes and the equatorial Pacific are likely to experience an increase in annual mean precipitation,” the IPCC synthesis report said of a scenario with continued warming. “In many mid-latitude and subtropical dry regions, mean precipitation will likely decrease, while in many mid-latitude wet regions, mean precipitation will likely increase.” The IPCC defines likely as having a 66 to 100 percent probability.

Averaged precipitation also hides the precipitation-related part of climate change that scientists are most confident about: increases in extreme precipitation.

“With global warming, there is more water vapor in the atmosphere and that tends to increase the intensity of certain precipitation events,” said Paul O’Gorman, an atmospheric scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in a phone interview. “But importantly, that applies mostly for heavy precipitation events.”

O’Gorman noted that models project that most places on Earth, with the exception of certain ocean regions, will see heavy precipitation getting stronger.

Downpours might be helpful in some cases, but they contribute to flooding, including flash flooding, runoff and soil erosion. And they can decrease water quality, as pollutants are washed into waterways humans rely on for drinking.

“It seems clear it’s not just going to be positive impacts,” O’Gorman said.

Angeline Pendergrass, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research who studies how precipitation changes with global warming, added that not only will heavy precipitation likely get heavier as the world warms, but light and moderate rainfall will become less frequent.

‘Shrink the Deserts’?

King jumped from his presumption of increased rainfall in “more and more places” to concluding that deserts might shrink in a warming future.

When asked about shrinking deserts, Pendergrass said, “I would say that’s not a thing. If anything, we expect deserts to expand.”

There is some evidence, she said, that the large-scale circulation patterns that govern rainfall in the tropics and lack of rain in the subtropics might extend, widening the area without much rain.

University of Maryland climate scientist Sumant Nigam has researched the Sahara and found that the desert has increased over the last century, in part due to climate change. He pointed us back to the long-term trends in observed rainfall that find precipitation increases and decreases in different places.

“Some of the decreasing regions overlap with current deserts, like the Sahara, which is expanding,” he said in an email. “That does not, however, rule out the possibility that precipitation may be increasing over another Desert, but this was certainly not the case over the largest one.”

O’Gorman said he was not aware of “any evidence that would suggest the deserts would decrease in extent.”

UNC’s Scheff, however, didn’t reject the idea because he said it depends on a person’s definition of a desert. Traditional definitions are pegged to precipitation amount, or the ratio of how much precipitation falls relative to the ability of the air to evaporate moisture — or what is called potential evapotranspiration. Under those definitions, he said, most research would suggest that deserts would stay about the same size or increase as warming continues. But if someone defines a desert by a lack of vegetation, deserts could shrink because global warming might increase plant growth, as we’ll explain below.

‘Expand the Green Growth’?

King also suggested that added precipitation would “expand the green growth.” Scheff said that some scientists, Scheff included, do think that a warming world might get greener — but not because of precipitation changes.

Instead, what drives the added growth, he said, is the increase in carbon dioxide, which, because of basic plant biology, would allow plants to get more of the gas they need without losing as much water.

Plants take in CO2 through tiny pores in their leaves called stomata. When the pores are open, however, plants lose water, so it’s a delicate balance for a hungry plant to get all the CO2 it wants to perform photosynthesis and grow, while not becoming dehydrated and wilting.

If there’s more CO2 in the air, which would be the case with increasing emissions, then plants don’t need to open their stomata as much, reducing their demand for water. Scheff said that might mean plants would be able to grow more on the same amount of water, and that with climate change, there’d be more plant growth.

While the idea is somewhat controversial, Scheff said there is evidence that it’s already happening. Satellite images, for example, show a greening trend in recent decades.

But, Scheff said, it’s not necessarily clear that the greening trend will continue as the world warms. “If it gets too hot,” he said, “plants might start dying.”

And while Scheff leans toward the green growth aspect being helpful overall, it would come with some downsides. Weeds and some allergens, such as ragweed, he said, are likely to do especially well under higher CO2. So that part of farming might become more difficult, and people’s allergies might get worse.

As Scheff noted in an email, and as we’ve written about before, plant biologists have also shown that crops would become less nutritious — a process Scheff likes to call “global starching” or “global fattening.”

“This is because with CO2 so abundant relative to other nutrients, the leaves become enriched in carbohydrates,” he explained, “but depleted in nitrogen- and phosphorus-bearing compounds like proteins and phytochemicals.”

As we’ve just established, King isn’t wrong that climate change might have some upsides. But it’s also true that there are many potential detrimental effects.

The exact impacts will vary region to region and will depend on how people adapt, MIT’s O’Gorman said. But, he said, there is a risk of “some very serious negative effects,” such as sea level rise and heat stress. “Those would outweigh many of the possible benefits,” he said.

Scheff said he considers CO2’s ability to reduce the water requirements of plants one of the few silver linings of climate change. “It’s a silver lining on some really scary stuff,” he said, also citing heat stress and sea level rise, as well as increases in extreme weather and the spread of disease. “There are way more bad things.”

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: