Summary

To hear President Donald Trump tell the story of the U.S. steel industry, it went from “dead” or “going out of business” to “thriving” all because of the 25% tariffs on imported steel he instituted in March 2018. While the tariffs have benefited U.S. steel producers, the reality of the impact isn’t that stark.

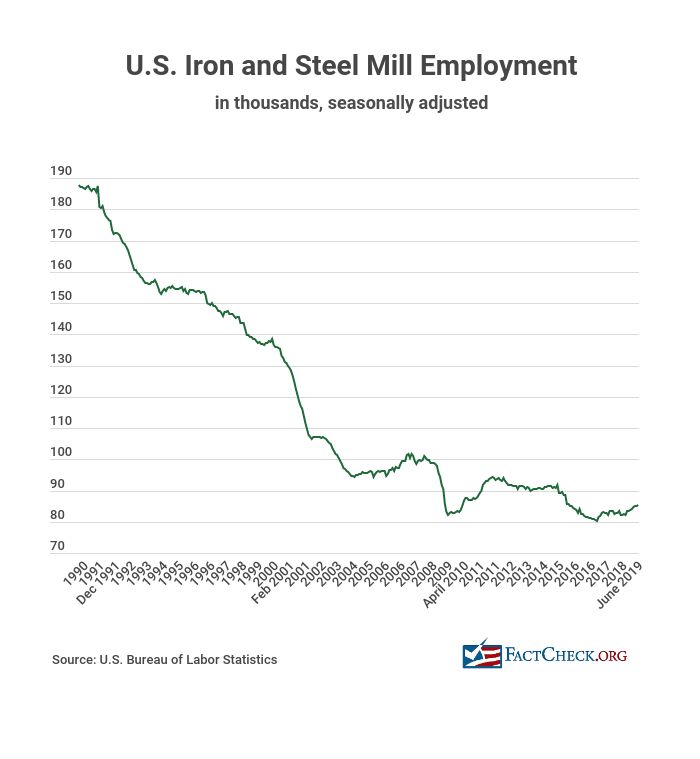

Domestic prices went up, for instance, but are now back down below the level they were when Trump was inaugurated. Production has gone up, too, but has been higher as recently as 2014. While the industry has announced several new investments, it’s simply not true that a new mill hadn’t been built in “30 years,” as the president wrongly claimed. Steel and iron mill jobs have increased, but they’re below the pre-Great Recession level. And technology has been a major factor affecting the long-term jobs decline.

Below, we’ll look at several claims Trump has made about the steel industry in recent months and how they measure up to the facts.

In late March 2018, Trump instituted the 25% tariffs on imported steel, and 10% tariffs on aluminum, with temporary exemptions for some countries, using his authority under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act. As required by the act, the Commerce Department had determined that the imports threatened national security. Two months later, he permanently exempted Argentina, Brazil and South Korea from the steel tariffs, with quotas on imports instead. Australia was also exempted, without a quota. In August 2018, Trump increased the tariff on steel from Turkey to 50%.

This year, in May, Trump lifted the tariffs on Canada and Mexico, and lowered the tariff on Turkey back to 25%. U.S. companies also have received exclusions on certain imports.

Analysis

‘Steel Was Dead’?

The claim: “And, by the way, steel — steel was dead. Your business was dead. Okay? I don’t want to be overly crude. Your business was dead. And I put a little thing called ‘a 25% tariff’ on all of the dumped steel all over the country. And now your business is thriving.” — Trump, in a speech in Monaca, Pennsylvania, Aug. 13

The facts: The 25% tariff on most imported steel helped the U.S. steel industry: Prices went up (though they’re now a little below what they were when Trump took office); productivity has increased; imports decreased. But Trump exaggerates the before-and-after picture.

The industry wasn’t “dead” before the tariffs, and there weren’t signs it was “going out of business” before his election, as he claimed on July 15. “If I hadn’t been elected, you would have no steel industry right now. It would be gone,” he said at a “Made in America” event at the White House.

It’s safe to say the entire U.S. steel industry would not be “gone” had Trump not been elected.

“The US industry has been vibrant, innovative and dynamic for the last 40 years,” James Moss, a partner in First River Consulting, told us in an email.

Moss, who has been a consultant to the steel industry for more than 20 years, said the U.S. has been a leader in the development, expansion and improvement of new technologies — such as the rise of the “minimills,” which produce steel from scrap metal using electric arc furnace, or EAF, technology. In 2002, minimills for the first time overtook the traditional blast furnace mills for steel production, according to a 2003 government report on the “changing profile” of the U.S. steel industry.

Moss described the change as “a classic US industrial story of ‘creative destruction,’” which “neither Europe nor Japan” allowed to happen, in part, because of the “industrial and social disruption” it would have caused.

“[T]here are two industries. There is the declining blast furnace based industry and there is the thriving and growing electric arc furnace based industry,” Moss said. “[T]he blast furnace industry has been dying, but the EAF industry has been thriving. As a result, the [U.S.] steel industry overall was and is far from dead.”

We’ll look at several metrics for the industry: production, prices, imports and capacity utilization.

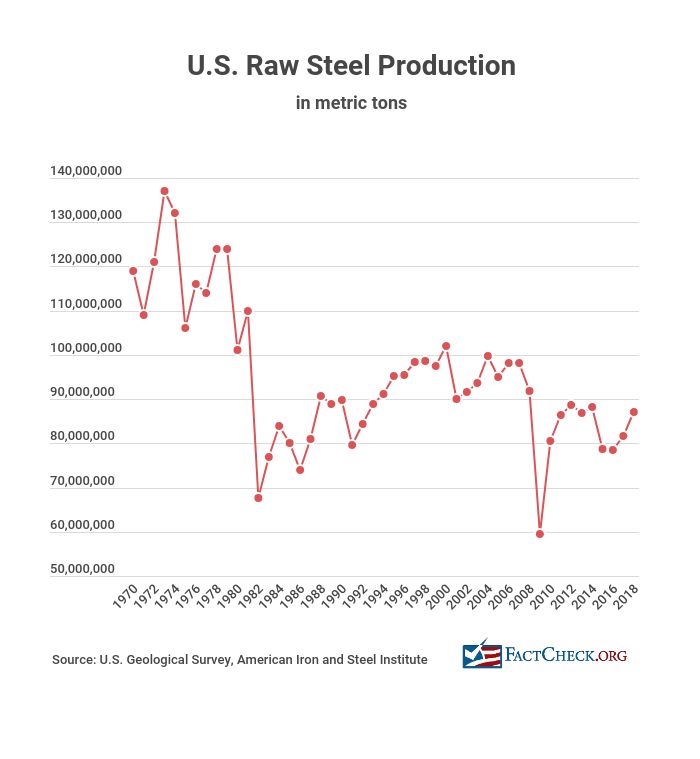

Production. Production is up since 2016, but it has been higher as recently as 2014. Figures from the U.S. Geological Survey, which gets its data from the American Iron and Steel Institute, show an increase in raw steel production from 2016 to 2018 of 10.8%. Production hit 87 million metric tons in 2018, but was 88.2 million metric tons in 2014.

“These are improvements, but we’ve seen improvement of similar double-digit magnitude in the past,” John Anton, director of steel analytics at IHS Markit, told us in citing monthly year-over-year production increases, from a high of 9.1% in January to a low of 3.1% in June. “We’ve also seen deep cuts” in production in the past, he added. “But production is up.”

Raw steel production in the U.S. topped 100 million metric tons in 2000, stayed in the 90-million range throughout that decade, and dropped considerably in 2009 during the Great Recession. Production rebounded the following year to 80.5 million metric tons, climbing higher in subsequent years before dropping 10.7% from 2014 to 2015 and remaining at that lower point through 2016.

What happened in 2015-2016? “Overproduction everywhere,” Anton said, which lowered prices. “By 2015, globally, not just the U.S., prices were absolutely atrocious.”

The industry “is filled with times when people get too enthusiastic,” Anton said. “It’s the history of the industry.”

Cicero Machado, principal analyst for Americas steel and iron ore at Wood Mackenzie, told us 2015-2016 was “a low point” for the industry. “Not only in the U.S., but certainly in other regions,” he said.

Demand, he said, wasn’t growing at a pace most steelmakers had expected. The Trump administration, Machado said, gave some “excitement” to steelmakers, with talk of tariffs (which were put into place) and investments in infrastructure (which haven’t materialized). That spurred production.

Much of what analysts told us about the industry pre- and post-tariff reflect classic supply and demand.

Tyler Kenyon, a vice president equity research analyst at the financial services firm Cowen, told us the tariffs prompted steel buyers to accumulate inventory, as the U.S. does rely on steel imports to meet demand. “Buyers were basically fearful of their ability to procure the material they needed,” Kenyon said. “What we saw was a massive inventory accumulation in excess of what underlying demand would suggest is appropriate.”

We asked Moss why — if the industry is as “vibrant” as he said — crude steel production has declined in recent decades. He gave three reasons, which he summed up as “part macro-economic, part technical and part wrong metric for measuring vitality.”

“Steel is a mature industry in a developed economy. We use less and less of it for every dollar of GDP. As much as our infrastructure needs renovating, we’re mostly built out. So we’re not a very steel intensive economy compared to say China,” he said. “Second, everything got lighter. Steel got lighter (thinner gauges) and stronger (better grades) so you use less of it for a given application. Plastic displaced some of it, too. So you would expect there to be a decline in use as an economy matures. Third, steel processing technology got much more efficient.”

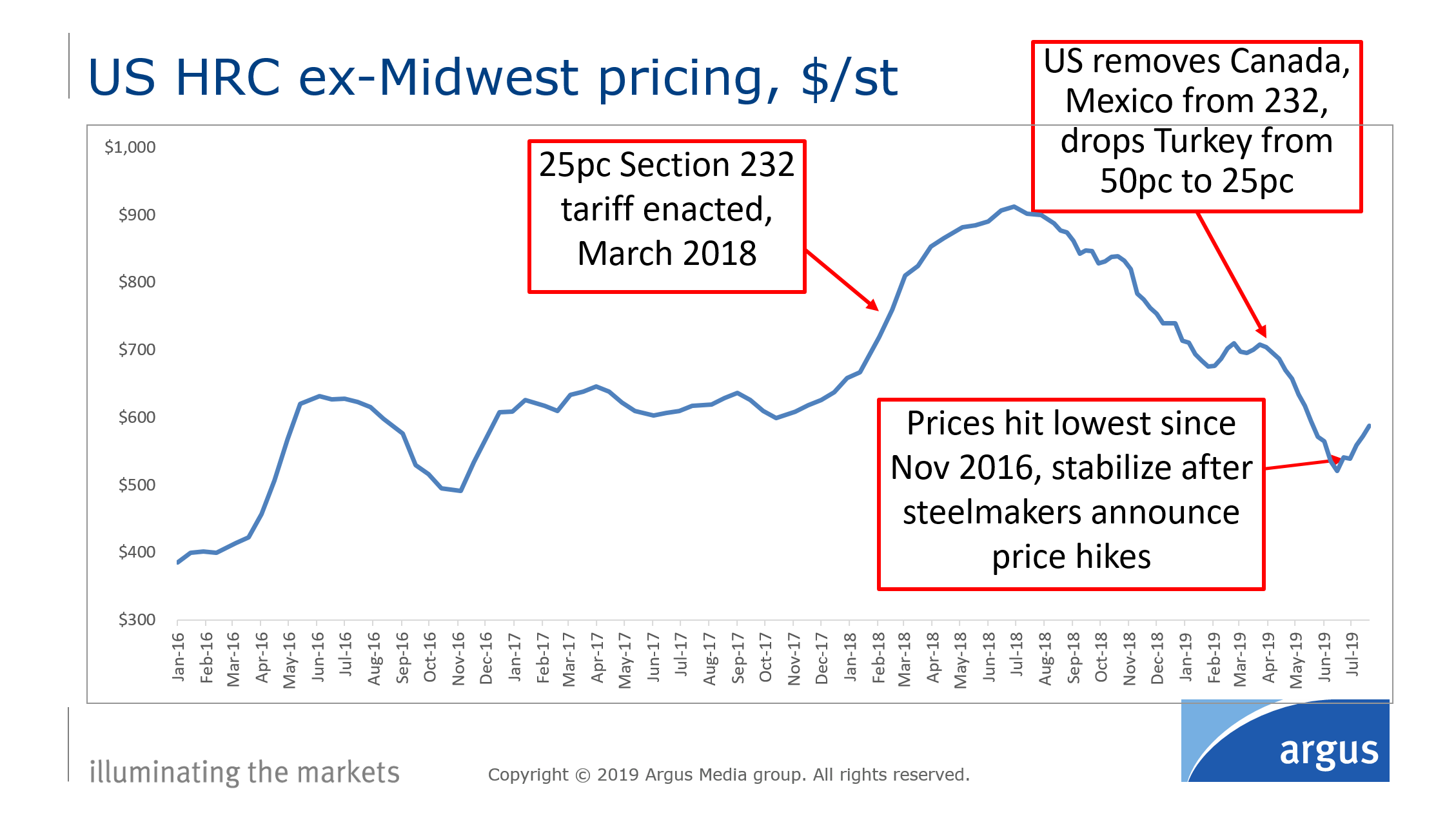

Prices. The 25% tariffs on imported steel then boosted prices in the U.S., at least for 2018, which was good news for steel companies’ bottom lines.

The Wall Street Journal editorial board – no fan of the tariffs – noted in a Feb. 3 editorial “all the superlatives” steel company executives used on investor calls. Nucor’s and Steel Dynamics’ CEOs said 2018 was “a record year” for their companies, and AK Steel’s and U.S. Steel’s CEOs said it was the best in the last 10 years.

With the price spike, the mills were “minting money,” the editorial argued, “to the detriment of America’s consumers and steel-reliant industries.” Ford Motor Co. said its tariff costs on steel and aluminum amounted to $750 million in 2018, and Caterpillar said it would raise prices in the second half of 2018 to offset higher costs due to the tariffs.

The steelmakers were “very happy,” Machado said, but the end users, probably not so much. There are “always two sides to this story.”

Machado shared yearly pricing figures from Wood Mackenzie for hot rolled coil, a benchmark of the industry. The annualized numbers show prices jumping from $687 per U.S. ton in 2017 to $918 in 2018 and back down to $682 this year. Prices hadn’t reached more than $900 per U.S. ton since hitting $964 in 2008.

Projections through 2025 from Wood Mackenzie show prices staying around $660 per U.S. ton in coming years, which is close to the average price from 2010 through 2017.

Weekly pricing data from Argus Media in the chart below show the impact of the tariffs, as prices increased in anticipation of the tariffs and continued to rise in the months immediately after the tariffs, hitting a high of $913 per U.S. ton the week of July 9, 2018, before falling and stabilizing this summer. Argus has the hot rolled coil price at $588 per U.S. ton the week of July 30, which is lower than it was the week of Trump’s inauguration.

The price spike in 2018 was unsustainable. U.S. steel prices “went up by more than the tariff rate,” said Anton, who put the increase at about 53% higher than European prices. “When you go too high,” he said, “you’re going to attract imports.” Prices now in the U.S. are only about 7% higher than European prices, he said.

“As soon as prices remain high, imports will still be something very attractive,” Machado said, noting that the tariff didn’t cover all countries, such as Brazil. “We saw a big jump in Brazilian imports into the U.S.”

And then there’s the issue of that accumulated inventory before the tariffs. For 2019, Machado said, “Demand is weakening, supply is outpacing demand.”

Kenyon said that over the last year, “we’ve seen the supply chain attempt to work down those inventories.”

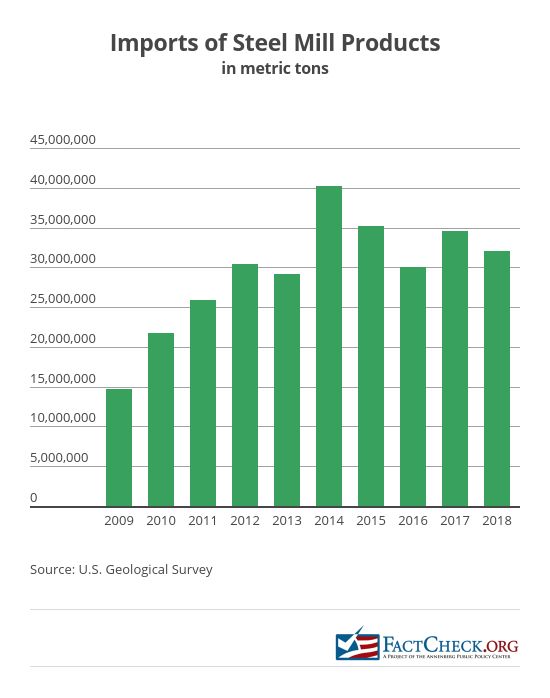

Imports. Machado said the tariffs did work in terms of keeping imports low, though Wood Mackenzie expects 2019 imports to be lower than 2018, more so because U.S. prices fell. (Commerce Department figures support the expectation that imports will decline for 2019.) End users of steel, he said, aren’t looking for imported steel as much because domestic prices are lower. But if prices increase again, “end users will find ways to import from some countries not in the 232 list.”

Import figures from the U.S. Geological Survey show imports fell by 7.5% from 2017 to 2018, but they’re up from 2016.

Other factors influencing U.S. prices, production and imports include the easing of the tariffs, weakening global demand and the economy generally.

In May, the Trump administration lifted the 25% tariff on steel imported from Canada and Mexico, and U.S. manufacturers have asked for and received exclusions for certain imported products. An April Congressional Research Service report said the administration had approved 16,500 steel exclusions out of a total of nearly 70,000 requests as of March 4.

Kenyon pointed out the tariffs now only apply to 30% of imports. Census figures for July show that the tariffs would have applied to 33% of total steel products imported, by quantity, once the exempted countries are excluded. That calculation doesn’t include the exclusions Commerce has approved for U.S. steel buyers.

The steel industry reflects broader economic factors, Blake Hurtik, editor of Argus Metal Prices, said. It follows consumption and construction activity, and global markets.

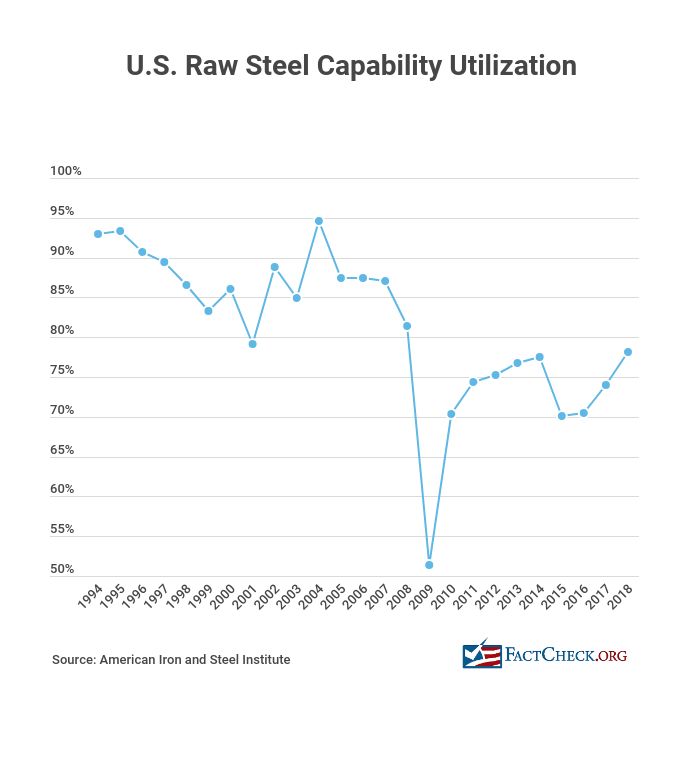

Capacity. The boost in price due to the tariffs and subsequent boost in cash flow for U.S. companies also prompted capacity expansions. “A lot of capital is being invested in the steel industry right now,” Kenyon said.

When Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross issued his report to the president on his investigations into imports of steel and aluminum and his recommendations for tariffs, he said an 80% capacity utilization was an important benchmark. “Each of these remedies is intended to increase domestic steel production from its present 73% of capacity to approximately an 80% operating rate, the minimum rate needed for the long-term viability of the industry,” the Feb. 16, 2018, press release from the Commerce Department said.

U.S. steel mills were operating at 80.3% of their capacity in the fourth quarter of 2018, according to figures provided to us from the American Iron and Steel Institute. An AISI spokesman said capacity for the first half of 2019 was 81.2%, and the rates in August also hovered around 80%.

AISI provided quarterly and yearly capability utilization rates dating back to 1994, which show rates well above 80% for most of that time period but not post-Great Recession.

Stock prices. Stock prices for U.S. steel companies hit peak prices when the tariffs were implemented, but they’ve tumbled since. U.S. Steel stock is down 75% from late February 2018 and 66% from January 2017, when Trump took office, while Nucor stock is down 30% from January 2018 and 19% since January 2017. However, Kenyon said once Trump was elected, investors were buying steel stocks in anticipation of pro-steel policies from the administration, and measuring the fall in stocks from peak levels due to the tariffs, “doesn’t truly reflect whether the industry is better off or not.”

New Steel Mills

The claim: “[W]e didn’t have a new mill built in 30 years, and now we have many of them going up.” — Trump, Aug. 13

The facts: Trump is “completely wrong about that,” Moss said, echoed by other experts.

First River Consulting provided us with charts that show the U.S. steel industry since 1989 has added about 40 million short tons, or U.S. tons, (as opposed to metric tons) of carbon steel capacity (excluding stainless steel).

Flat (or sheet and plate) steel — which is used for cars and washing machines, for example — is the most in demand, and accounts for 80% of the new capacity since then, Moss said. Long steel capacity accounts for the rest.

In all, Moss identified for us 23 new steel mills that added 33 million tons of annual capacity since 1989. Most of the new mills opened between 1992 and 2002. But eight of them have been built since 2007, including these three large-capacity mills:

- Big River Steel announced plans for a 1.6-million-ton-annual-capacity steel mill in 2013, broke ground on construction in 2014, and started production in December 2016.

- ThyssenKrupp USA announced in May 2007 that it would build a steel mill in Alabama, which opened in late 2010 at a final cost of $3.6 billion. It has the annual capacity to produce 4.7 million tons of carbon steel — making it the single largest new plant that has opened since 1989, according to First River Consulting.

- In 2007, Severstal completed construction of “the newest and most advanced electric arc furnace facility in the world,” as a corporate press release described it. The company doubled the size of the facility when it completed phase two of the project in 2011, increasing annual steel production capacity to 3.4 million tons.

Although it is “not true” that the U.S. hasn’t built a new mill in 30 years, the president is right that there has been a lot of investment in the steel industry recently, said Machado at Wood Mackenzie. The “amount of announcements that were made last year … was substantial,” he said.

Six new steel mills with a combined annual capacity of 7.2 million tons have been announced since 2017, according to First River. The largest is a mill in Sinton, Texas, which Steel Dynamics Inc. announced in late 2018. The mill will have an annual capacity of approximately 3 million tons.

All of the new facilities use the electric arc furnace technology, Moss said.

“No one will build a new blast furnace based steelmaking facility again in the US,” Moss said, because they are “too expensive to build and maintain, too dirty and come with a whole bunch of corollary investments that make it hard for the steel mills they support to make money.”

In fact, U.S. Steel in early March 2018 announced it would restart a blast furnace at its Granite City, Illinois, plant that had been idle since December 2015, citing “anticipated increased demand” from Trump’s action on tariffs. But by June, U.S. Steel said it would idle two other blast furnaces in the U.S. and one in Europe, and restart production “when market conditions improve.” In August, it announced it would idle another plant in Indiana this fall.

Hurtik at Argus Metal Prices said the big capacity announcements are scrap-based, not blast furnaces. “Not everybody is going to be winner. Steel is not a homogeneous thing,” he said.

Steel Jobs

The claim: “We’re putting … our steel workers back to work.” — Trump, at a campaign rally, Cincinnati, Ohio, Aug. 1

The facts: Iron and steel mill jobs have gone up by 4,500 from January 2017 to June, a 5.6% increase, according to the latest figures available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The level of employment in June — 85,300 workers — was 16% below the 101,700 workers in May 2007, months before the Great Recession.

When we contacted the Trump campaign about the president’s claims, one factor Deputy Communications Director Zach Parkinson pointed to was job growth under Trump and a 13,500 drop in those jobs during Barack Obama’s presidency. That figure is correct. Iron and steel mill jobs under Obama declined during the Great Recession, rose back up by late 2011 to the level they were when he had taken office, and slowly declined again, most considerably in 2016.

The long-term trend for the industry has been a decline in employment, as the chart below shows, but much of that is due to changes in technology, experts told us.

Steel and iron mills employed 187,800 people in January 1990, and it’s less than half that figure now. Anton at IHS Markit said that’s primarily due to new technology and more efficient mills. It takes fewer people to make the same amount of steel. “Imports are a problem,” he said, but improved efficiency is the “No. 1 reason that you don’t have as many people employed.”

The Trump campaign also pointed to news of wage increases negotiated by unions at U.S. Steel and the mining company Cleveland Cliffs in 2018 as evidence of Trump’s positive impact on the industry.

The United Steelworkers press release on the wage hikes at U.S. Steel noted the company projected earnings of $2 billion in 2018 — as we’ve explained, a time of high prices for domestic steel — and “workers rightly wanted a share of that success,” USW International President Leo W. Gerard said. But it took a unanimous union vote to strike in September to get the new wage agreement.

Steel Dumping

The claim: “And they still dump, but now the United States takes in billions of dollars and the dumping is much less, and the steel companies are thriving again.” — Trump, Aug. 13

The facts: It’s unclear exactly what impact the tariffs have had on “dumped” steel, though, as we said, imported steel overall declined from 2017 to 2018. And 2019 imports may be lower still, though Machado said that’s mainly because U.S. prices fell.

At the White House on July 15, Trump said, “We put massive tariffs on dumped steel.” But the tariffs were broader than individual antidumping measures, which were already in place.

Antidumping cases are specific to the product, country and sometimes to the company, Anton said, whereas the Section 232 tariffs were on every country, except certain exemptions. He said dumping cases are filed “every year,” including cases under then-President Barack Obama.

On March 1, 2016, Obama’s Commerce Department announced a 266% duty on cold-rolled flat steel from China, as well as duties on certain steel from Brazil, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the U.K. It upped that to 522% in May 2016.

At the time Trump’s tariffs were imposed, the U.S. had 164 antidumping and countervailing duty orders in effect for steel that restricted imports of individual steel products from certain countries — including Brazil, China, India, Japan, South Korea and Turkey, according to the Commerce Department’s Jan. 11, 2018, report recommending increasing tariffs on all steel imports. That represented a 60% increase since the department’s last Section 232 investigation of the steel industry in 2001, the report said.

(As the Congressional Research Service explained in an April report, antidumping duties are imposed when the U.S. International Trade Commission determines that goods are sold at less than fair value in the U.S. market, while countervailing duties are imposed when foreign governments are subsidizing the cost of those cut-rate imports.)

The Commerce report said antidumping and countervailing actions “can address specific instances of unfairly traded steel products,” but they are not enough in this case.

“[G]iven the large number of countries from which the United States imports steel and the myriad of different products involved, it could take years to identify and investigate every instance of unfairly traded steel, or attempts to transship or evade remedial duties,” the report said.

The U.S. doesn’t get much of its imported steel from China, which was the 11th largest source of steel for the U.S. in 2018, the same spot it held in 2016. China was the seventh largest source of steel imports in 2015, but the metric tons imported dropped considerably the following year, by 63%, according to figures from the Department of Commerce. The top three sources of U.S. imports are Canada, Brazil and Mexico.

But China is the No. 1 steel producer in the world, by a long shot.

Hurtik at Argus Metal Prices told us even if China isn’t selling steel to the U.S., it’s selling steel somewhere. “It has an impact no matter where it ends up.”

The April CRS report said, “While China is the world’s largest steel producer, accounting for roughly 45% of global capacity, relatively little Chinese steel enters the U.S. market directly, due to extensive U.S. dumping and subsidy determinations, but the large amount of Chinese production acts to depress prices globally.”

Looking Ahead

There’s no expiration date on the 232 tariffs. The CRS report said the president’s actions can remain in place “for such time, as he deems necessary to adjust the imports” so they don’t “threaten to impair the national security,” according to the statute.

Machado told us that while demand is weakening, Wood Mackenzie expects some growth in demand over the next two years, driven by commercial construction and infrastructure. He also expects imports to increase, partly because “end users will find ways to import” if prices are higher in the U.S. and partly because he expects that free trade policies would be restored.

The overall impact on the U.S. economy, as opposed to only the steel industry, is more complicated. The CRS report said that “generally” economic models would show the negative effect of higher prices for those using imports is greater than “the benefit of higher profits and expanded production in the import-competing industry and the additional government revenue generated by the tariff.” There’s also an impact due to retaliatory tariffs, which were imposed on $23 billion of U.S. goods in 2018 by six trading partners.

But CRS said the direct economic impact of the steel and aluminum tariffs “may be limited” because such products made up only 2% of all imports in 2018.

Sources

Congressional Research Service. “Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress.” updated 2 Apr 2019.

Presidential Proclamation Adjusting Imports of Steel into the United States. Whitehouse.gov. 22 Mar 2018.

Presidential Proclamation Adjusting Imports of Aluminum into the United States. Whitehouse.gov. 22 Mar 2018.

Federal Register. Proclamation 9740 of April 30, 2018, Adjusting Imports of Steel Into the United States. gpo.gov. 7 May 2018.

Federal Register. Proclamation 9739 of April 30, 2018, Adjusting Imports of Aluminum Into the United States. gpo.gov. 7 May 2018.

Federal Register. Proclamation 9759 of May 31, 2018, Adjusting Imports of Steel Into the United States. gpo.gov. 5 Jun 2018.

Trump, Donald (@realDonaldTrump). “I have just authorized a doubling of Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum with respect to Turkey as their currency, the Turkish Lira, slides rapidly downward against our very strong Dollar! Aluminum will now be 20% and Steel 50%. Our relations with Turkey are not good at this time!” Twitter. 10 Aug 2018.

Proclamation on Adjusting Imports of Steel into the United States. Whitehouse.gov. 19 May 2019.

Speech: Donald Trump Addresses Energy and Manufacturing Growth in Monaca, PA. Transcript. Factba.se. 13 Aug 2019.

Remarks: Donald Trump Hosts Made in America Product Showcase at The White House. Transcript. Factba.se. 15 Jul 2019.

U.S. Geological Survey. Iron and Steel Statistics. last modified 19 Jan 2017.

U.S. Geological Survey. Iron and Steel Statistics and Information, Mineral Commodity Summaries. usgs.gov. accessed 28 Aug 2019.

Anton, John, IHS Markit. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 20 Aug 2019.

Machado, Cicero, Wood Mackenzie. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 19 Aug 2019.

Kenyon, Tyler, Cowen. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 21 Aug 2019.

“Steel Tariff Profiteers.” Wall Street Journal Editorial Board. 3 Feb 2019.

Department of Commerce. U.S. Imports of Steel Mill Products, quantity in metric tons. last modified 2 Aug 2019.

Hurtik, Blake, Argus Metal Prices. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 22 Aug 2019.

Department of Commerce. “Secretary Ross Releases Steel and Aluminum 232 Reports in Coordination with White House.” Press release. 16 Feb 2018.

American Iron and Steel Institute. This Week’s Raw Steel Production. steel.org. accessed 27 Aug 2019.

Murphy, Jake, communications manager, American Iron and Steel Institute. Email to FactCheck.org. 27 Aug 2019.

Yahoo! Finance. U.S. Steel stock prices. accessed 27 Aug 2019.

Yahoo! Finance. Nucor Corp. stock prices. accessed 27 Aug 2019.

Speech: Donald Trump Holds a Political Rally in Cincinnati, Ohio. Transcript. Factba.se. 1 Aug 2019

Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National). All employees, thousands, iron and steel mills and ferroalloy production, seasonally adjusted. Bureau of Labor Statistics. data extracted 28 Aug 2019.

United Steelworkers. “USW Members Vote to Ratify 4-Year Contract with U.S. Steel.” Press release. 13 Nov 2018.

United Steelworkers. “USW Members Vote to Ratify Four-Year Contract with Cliffs.” Press release. 12 Oct 2018.

Miller, John W. and William Mauldin. “U.S. Imposes 266% Duty on Some Chinese Steel Imports.” Wall Street Journal. 1 Mar 2016.

“Obama Front-Runs Trump on China.” Wall Street Journal editorial page. 19 May 2016.

Department of Commerce. “The Effect of Imports of Steel on the National Security, An Investigation Conducted Under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as Amended.” 11 Jan 2018.

Cooney, Stephen. “The American Steel Industry: A Changing Profile.” Congressional Research Service. 10 Nov 2003.

Moss, James. Partner, First River Consulting. Email to FactCheck.org. 16 Aug 2019.

Moss, James. Partner, First River Consulting. Email to FactCheck.org. 21 Aug 2019.

“Big River Steel Mill: America’s Newest Steel Mill.” Big River Steel. Sep 2017.

“ThyssenKrupp Supervisory Board gives green light to steel mill in the USA.” Press release. ThyssenKrupp. 5 Nov 2007.

Underwood, Jerry. “ThyssenKrupp’s Alabama steel operation hires 1,000th worker.” Birmingham News. 6 Jul 2010.

“Severstal Columbus Unveils $550 Million Phase II Facility Expansion.” Press release. Severstal. 16 Nov 2011.

“US carbon sheet & plate capacity additions.” First River Consulting. PowerPoint. 16 Aug 2019.

“Carbon long products capacity additions.” First River Consulting. PowerPoint. 16 Aug 2019.

“Announced EAF expansions.” First River Consulting. PowerPoint. 16 Aug 2019.

“Steel Dynamics Announces Planned New Flat Roll Steel Mill Site Selection.” Press release. 22 Jul 2019.

Sandoval, Dan. “SDI to build EAF mill in Southwest US.” Recycling Today. 29 Nov 2018.

“United States Steel to Restart Granite City Works Blast Furnace, Steelmaking Facilities.” Press release. United States Steel Corporation. 7 Mar 2018.

“United States Steel Corporation Provides Second Quarter 2019 Guidance.” Press release. United States Steel Corporation. 18 Jun 2019.

Census Bureau. U.S. Imports for Consumption of Steel Products: Preliminary July 2019. 23 Aug 2019.