In announcing “phase one” of a tentative trade deal with China, President Donald Trump wrongly stated that the “all-time high” for U.S. agricultural exports to China was “$16 or $17 billion.” Actually, it was nearly $26 billion in 2012.

By misstating the record value of exports, Trump also greatly exaggerated the potential impact of the tentative trade deal.

Trump made his remarks on Oct. 11 at a joint appearance with Chinese Vice Premier Liu He and U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin.

The president called “phase one” of the tentative trade deal a “tremendous deal for the farmers.” Mnuchin said China had agreed to increase the purchase of U.S. agricultural goods over the next two years, and that the Chinese would reach the point where they will be buying $40 billion to $50 billion annually.

We don’t have any details on the deal, which Trump has said will take three or four weeks to get into writing.

But what we do know is that Trump was wrong when he repeatedly claimed that China has never purchased more than $16 billion to $17 billion in U.S. agricultural products before.

Trump, Oct. 11: So, they were purchasing $16 or $17 billion at the highest point, and that’ll be brought up to $40 billion to $50 billion. … They intend to go up, ultimately, once the agreement is signed, from $40 to $50 billion. And, really, from — that was from a base of probably $16 billion, and right now it’s $8 billion. … Going from $8 billion and then to $16 billion, which was their all-time high, to $40 to $50 billion.

At another point, Trump said “it was about $2 or $3 billion; they got down pretty low. But if you take — the highest it ever was was $16 billion, and we’re bringing that to $50 billion.”

Jason Grant, director of the Center for Agricultural Trade at Virginia Tech University, told us, “There seems to be some careless numbers being thrown out here.”

For one thing, Trump’s claim that China’s purchase of U.S. agricultural goods “got down pretty low” at just “$2 or $3 billion” is misleading, because that came the year after China became a member of the World Trade Organization on Dec. 11, 2001. “In 2002 – right after China acceded to the WTO – we exported only $2 billion worth of ag exports to China,” Grant said.

And Trump is wrong about his figure for the “all-time high.”

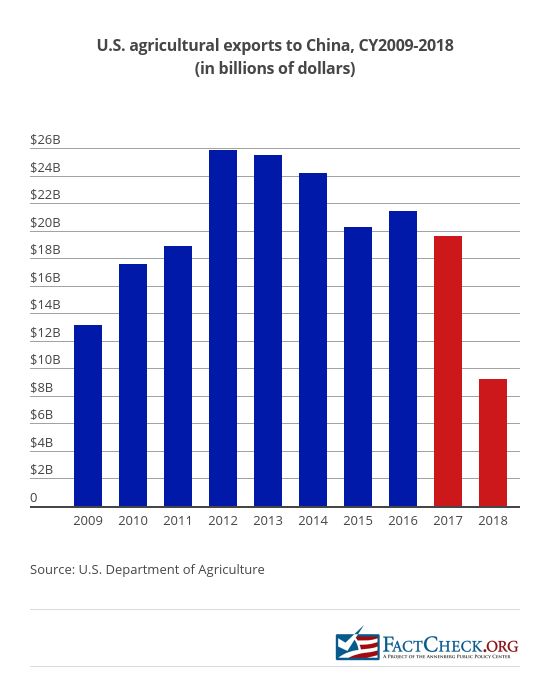

Both Grant and Chad E. Hart, an associate professor of economics and crop markets specialist at Iowa State University, told us the record high was set in 2012 at $25.9 billion.

U.S. Department of Agriculture data confirms that the figures were indeed $2 billion in calendar year 2002 and nearly $26 billion in 2012. In 2018, the figure was $9.2 billion — the lowest it had been since 2007, a direct outcome of the ongoing trade war that Trump initiated with China that resulted in higher tariffs.

Using USDA data, we produced the chart below:

In presenting false and misleading low figures, the president made the tentative trade deal seem larger than it may be.

Trump, Oct. 11: A purchase of — from 40 to 50 billion dollars’ worth of agricultural products. To show you how big that is, that would be two and a half, three times what China had purchased at its highest point thus far.

That’s wrong, too.

If U.S. ag exports to China do reach $40 billion in the future, that would be a 54% increase, and $50 billion would be 93% — not “two and a half, three times what China had purchased at its highest point.”

That is still a substantial increase, but not nearly as high as Trump said, and we don’t know if U.S. agricultural exports to China will ever get that high.

Hart, the Iowa State University professor, said that “it’s hard to imagine that you can suddenly double the amount of imports going into there with its economy slowing down.” Hart said the biggest commodity that China imports from the U.S. is soybeans, which are used to feed livestock, particularly pigs. But African Swine Fever is “endemic across China,” as the USDA put it, so Hart questions China’s need to import more soybeans.

“What is China going to do with it?” Hart said, referring to soybeans that are usually fed to pigs. “It’s not whether we can produce it; yeah, we can. Is there demand enough in China? Probably not.”

Hart said he is cautiously optimistic about the president’s direct involvement in the trade talks — a possible sign that there will be a deal this time after several false starts in a trade war that has driven down U.S. agricultural exports to China. But, he added, the impact on farmers won’t be known for quite some time.

“The real devil here will be in the details,” he said.