In a tweet, President Donald Trump boasted of the lowest cancer death rate on record, and implied that his administration was responsible for the achievement. While he’s right about the statistic, the improved death rate is the result of decades-long efforts on cancer prevention, detection and treatment.

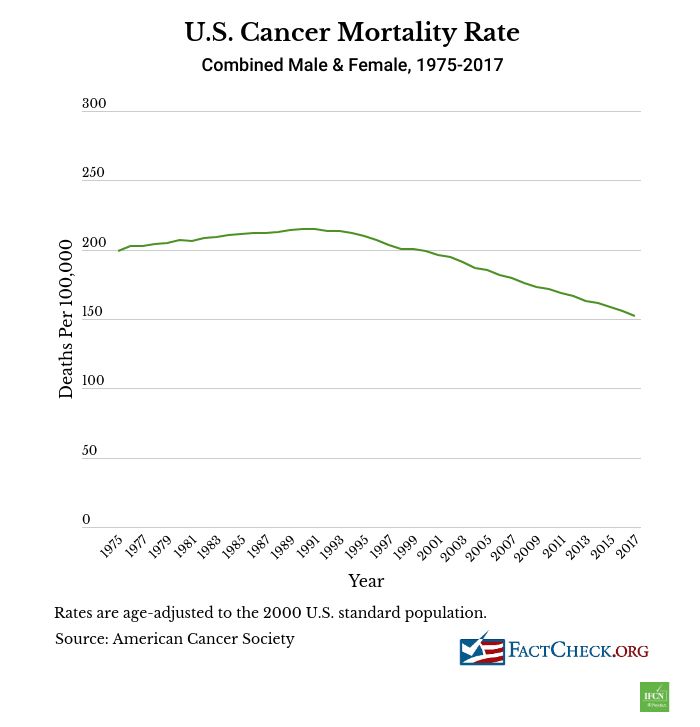

In fact, the cancer death rate has declined every year since 1991.

In a Jan. 9 tweet, Trump appeared to reference the results of a newly released set of cancer statistics from the American Cancer Society when he bragged about the nation’s cancer mortality rate, adding, “A lot of good news coming out of this Administration.”

U.S. Cancer Death Rate Lowest In Recorded History! A lot of good news coming out of this Administration.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 9, 2020

The White House did not reply to our request asking about a source for the president’s comment. But the day before his Twitter message, the flagship journal of the American Cancer Society published its annual update of cancer statistics for the U.S.

The report, which was widely publicized, noted the continuing decline of the all-cancer mortality rate in the U.S., and said that the 2.2% drop in the death rate from 2016 to 2017 was the largest single-year decline. Cancer deaths fell from just under 156 per 100,000 people in 2016 to a bit over 152 deaths in 2017 — which is the most recent year for mortality data.

The report, which was widely publicized, noted the continuing decline of the all-cancer mortality rate in the U.S., and said that the 2.2% drop in the death rate from 2016 to 2017 was the largest single-year decline. Cancer deaths fell from just under 156 per 100,000 people in 2016 to a bit over 152 deaths in 2017 — which is the most recent year for mortality data.

The report did not specifically state that the 2017 death rate was the lowest on record, but we checked with the lead author of the report, cancer epidemiologist Rebecca Siegel, who confirmed in an email that it was. Going back to 1930, which is when the American Cancer Society begins tracking cancer mortality, “the rate in 2017 is lower than ever before for both sexes combined,” she said, although the death rate is not yet the lowest for males individually.

Contrary to Trump’s intimation, however, the death rate improvement is a product of years of effort coming to fruition, not his administration’s one year of being in office.

“The mortality trends reflected in our current report, including the largest drop in overall cancer mortality ever recorded from 2016 to 2017, reflect prevention, early detection, and treatment advances that occurred in prior years,” Gary M. Reedy, CEO of the American Cancer Society, said in a statement provided to us.

Reedy added that while Trump has signed spending bills that have provided funding increases to the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute, “the impact of those increases are not reflected in the data contained in this report.”

It should be noted that while Trump has approved budget increases for cancer research, he has consistently proposed cuts to the NIH and the NCI, the government’s main agency responsible for cancer research and training.

In fiscal year 2020, for example, Trump proposed a nearly $900 million, or 15%, decrease to NCI — one of the largest proposed cuts within the NIH. Congress, however, did not go along, and instead increased the NCI’s budget by almost $300 million.

Trump has focused his support for cancer research on childhood cancers, announcing a $500 million, decade-long initiative in his 2019 State of the Union speech. The president’s fiscal 2020 budget request for the NIH included a $50 million increase in pediatric cancer research, even as it called for a deep cut in NCI’s overall funding.

The most recent drop in the cancer death rate is part of a now 26-year decline in the overall cancer mortality rate, which has fallen 29% since the peak rate in 1991, the new American Cancer Society report says.

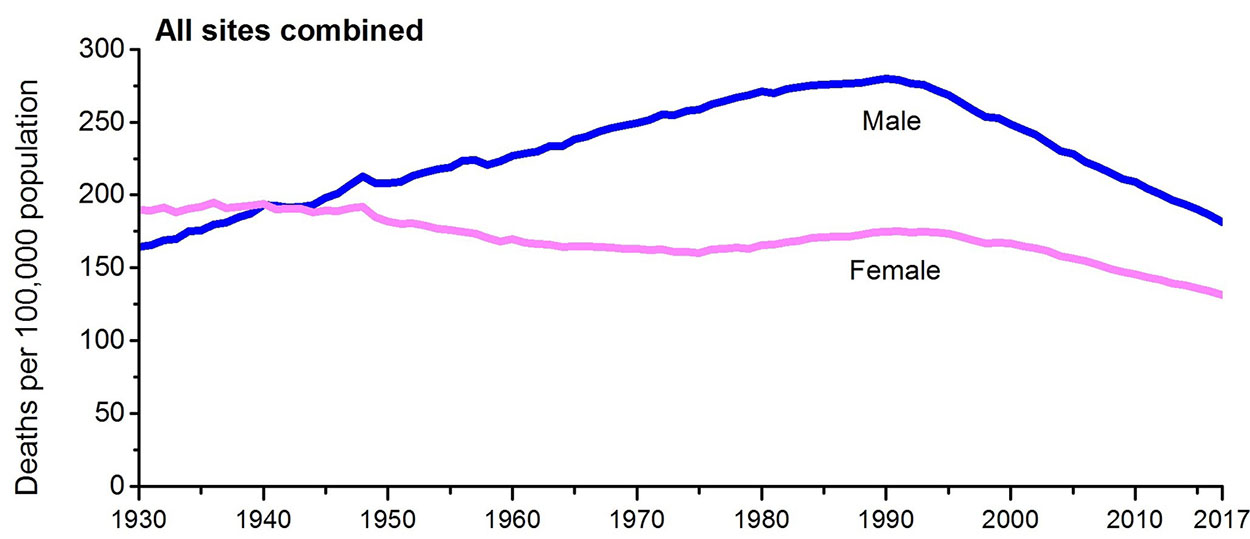

For males, the cancer death rate peaked much higher than for females, but has since declined more rapidly. That’s in part due to historical differences in cigarette smoking; American females picked up the habit later, but also have been slower to quit.

For males, the cancer death rate peaked much higher than for females, but has since declined more rapidly. That’s in part due to historical differences in cigarette smoking; American females picked up the habit later, but also have been slower to quit.

Siegel said the falling death rate is primarily because of reductions in smoking that began in the 1960s. As a result of fewer people smoking, fewer people developed and then died, not only from lung cancer, but from at least 11 other smoking-related cancers, she said. According to the NCI, those cancers include kidney, bladder, liver, stomach, colon, and cervical cancer.

The especially large decline from 2016 to 2017, Siegel said, was largely because of even more rapid declines in lung cancer mortality. Without lung cancer being included, she said, the rate of decline would have been only 1.4%, rather than 2.2%.

As recently as 2008 to 2013, the lung cancer death rate was falling at a slower pace, around 2.4% per year, said Siegel. But between 2013 and 2017, the annual decrease was 4.3%. She attributed the accelerated decline to a continued drop-off in smoking as well as treatment advances that have taken hold in the last decade. These include better methods of staging lung cancer, which can allow for more optimal treatment; improvements in surgery, such as the development of less invasive video-assisted thoracic surgery; advances in radiation therapy; and more effective drugs, including more targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

“We know this because survival rates have increased by the same magnitude for every stage of diagnosis,” Siegel said, “and treatment differs based on stage.”

Other cancer types have seen even larger reductions in the death rate in recent years. For example, the mortality rate for melanoma, a type of skin cancer, declined by a whopping 7% per year for 20- to 64-year-olds for the 2013 to 2017 period, per the new report. That dramatic improvement is tied to drugs that became available in 2011, including the first Food and Drug Administration-approved checkpoint inhibitor, Yervoy, which was created based on basic research discoveries going back to 1995. As we’ve explained before, checkpoint inhibitors are immunotherapy drugs that block surface molecules tumor cells use to hide from the immune system, allowing the body to recognize and kill them.

Because lung cancer kills so many more people — more than breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers combined, Siegel noted — these particularly rapid declines do less than the more modest lung cancer rate drops to drive down the overall death rate.

Despite the largely positive trends, the American Cancer Society paper estimated that lung cancer would still be the biggest cancer killer of both males and females in 2020 — and responsible for nearly a quarter of all cancer deaths.

The cancer death rate is indeed at a record low, but it’s misleading for Trump to claim credit when the reductions are due to factors that are many years, if not multiple decades, in the making.