Joe Biden claimed that farm bankruptcies increased last year “due largely to Trump’s unmitigated disaster of a tariff war.” International trade was a factor, but there were additional reasons that predate the trade war — such as years of relatively weak prices, declining incomes and rising farm debt, according to agricultural economists and government reports.

“The bankruptcy wave this year has roots that go back several years,” Chad E. Hart, an associate professor of economics and crop markets specialist at Iowa State University, told us in an email.

The former vice president and presumptive Democratic presidential nominee made his remarks about farm bankruptcies at a “virtual rally in Milwaukee.” Biden, who has been staying home in Delaware during the coronavirus pandemic, spoke online to a few Wisconsin Democrats who hosted the online event.

Wisconsin has been reliably Democratic in recent presidential elections — until 2016, when Trump became the first Republican to win the state since 1984. He did so by less than 23,000 votes, making Wisconsin a key swing state in the 2020 election.

Wisconsin has been reliably Democratic in recent presidential elections — until 2016, when Trump became the first Republican to win the state since 1984. He did so by less than 23,000 votes, making Wisconsin a key swing state in the 2020 election.

Biden criticized President Donald Trump’s handling of the pandemic, but said the president’s damage to the U.S. economy began long before the health crisis — citing Trump’s trade war with China, which began in early 2018 and resulted in retaliatory tariffs on U.S. farm products.

Biden, May 20: This crisis hit us harder and will last longer because he spent the last three years undermining the foundation of our economic strength. Farm bankruptcies jumped 20% last year due largely to Trump’s unmitigated disaster of a tariff war.

Biden is correct about farm bankruptcies, which increased 24% for the 12 months ending September 2019, up to 580 from 468 the previous 12 months, and 20% for the 12 months ending December 2019, up nearly 100 filings to 595, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation. The Biden campaign sent us links to the farm bureau reports and news articles about them.

Since those reports, farm bankruptcies have continued to rise. There were 627 for the 12-month period ending March 31, 2020, according to U.S. Bankruptcy Courts data.

But John Newton, the farm bureau’s chief economist, told us there are several reasons for the increase in bankruptcies — not just the trade war. “It’s one piece of many pieces that combined to hurt the farm economy,” Newton told us in an interview.

The farm bureau’s February report, which Newton wrote, says the increase “was not unanticipated given the multi-year downturn in the farm economy, record farm debt, headwinds on the trade front and recent changes to the bankruptcy rules in 2019’s Family Farmer Relief Act, which raised the debt ceiling to $10 million.”

The Family Farmer Relief Act made more agricultural businesses eligible for bankruptcy by raising the limit on debt for those filing under Chapter 12 from $4.1 million to $10 million, Newton said. About 7,700 farms have debt in excess of $4.1 million, according to a report last year by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service on farm debt and Chapter 12 bankruptcy filings.

“I don’t think it was entirely one issue or another,” Newton said.

Newton’s observation is consistent with what we heard from other agricultural economists.

“I agree with AFBF on the bankruptcies,” Hart told us in an email. “There are a number of reason why bankruptcies are on the rise. The trade war is part of it, but we can’t say that it’s the overriding factor. Given farm incomes over the past few years (going back to 2013), we knew the likelihood of more bankruptcies was higher, even before the trade fight.”

Joseph Glauber, a former chief economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture from 2008 to 2014, told us it is impossible to know what caused the bankruptcies because so little information about those farm operations is publicly available.

“I don’t think it is knowable,” Glauber, a senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington, D.C., said when we asked what was the primary factor responsible for the increase. “Were they cotton producers? Dairy farms? We just don’t know anything about those farms. We just know they filed bankruptcy under a tax code that is available only to farmers.”

Let’s look at some of the factors that caused what the farm bureau’s October report called a “prolonged downturn in the farm economy.”

Declining Income, Rising Debt

Hart, of Iowa State University, said farmers have been in an economic slump since 2014. That’s when net farm income first started to fall.

Net farm income over the last 10 years, adjusted for inflation, peaked in 2013 at $139 billion (in 2020 dollars), according to USDA data. It declined over the next three years, falling to a low of $67 billion in 2016. Since then, it has increased, but not to the 2013 level. It was $87 billion in 2018.

“The farm balance sheet took its biggest hits in 2014 and 2015,” Hart said, “and for some farmers, the years since then have been a slow erosion of farm net worth (debts rising faster than incomes).”

The farm bureau noted that the “farm debt in 2019 is projected to be a record-high $416 billion.”

Glauber, of the International Food Policy Research Institute, said that farmers “bought tons of equipment” after 2013 in anticipation of continued growth that didn’t fully materialize — in part because of domestic and global overproduction — resulting in higher debt levels cited in the farm bureau report.

Farm debt, adjusted for inflation, has increased every year since 2013, and is now “near the peak levels of the late 1970s and early 1980s,” according to an October report by the USDA’s Economic Research Service. At the same time, real estate prices have plateaued in 2014, the report said.

As a result, the farm sector’s debt-to-asset ratio — which is “a measure of a farm business’s leverage and is used by lenders as an indicator of bankruptcy risk” — has been on the rise since 2012, the report said.

Since 2012, “the market for land has weakened and the debt-to-asset ratio has trended upward,” the report said. “The debt-to-asset ratio is now above its 10-year average, though it remains low by historic standards.”

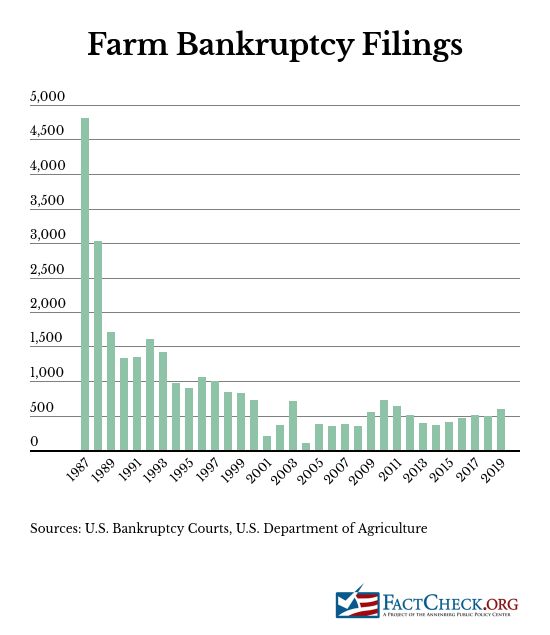

Glauber and Newton both stressed that the current plight of farmers, when put into historical context, isn’t close to the farm crisis of the 1980s.

“If you look at all our reports on bankruptcies, we’ve indicated that while these bankruptcies are going up they are still well below the 1980s — the last time we had a farm crisis,” Newton, of the farm bureau, said.

How far below the 1980s? As the chart below shows, farm bankruptcy filings peaked in 1987 at 4,812 — more than eight times the 595 filed in 2019 — according to a 2004 USDA report (appendix table 2).

Commodity Prices ‘Collapse’

So what has happened in recent years to make farm income fall?

“Commodity prices collapsed in 2015,” Newton said.

The impact of the decline in commodity prices was reflected in the annual farm income outlook report by the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service for 2017. The CRS report said there had been “three consecutive years of decline” that was “primarily a result of the significant decline in most farm commodity prices since the 2013-2014 period.” Looking ahead to 2017, the USDA’s Economic Research Service projected a rise in net farm income, the CRS report said.

Both soybeans and corn — “the two largest U.S. commercial crops in terms of both value and quantity” — experienced years of high production and stock surpluses that drove prices lower, CRS said in its report.

“For the past several years, U.S. corn and soybean crops have experienced remarkable growth in both productivity and output,” the 2017 report said. “Both crops had record harvests in 2014, above-average harvests in 2015, and record harvests again in 2016, thus helping to build stockpiles at the end of the marketing year … and pressure prices lower in U.S. and international markets” in 2017.

Net farm income did rise in 2017, both in nominal and inflation-adjusted figures, but it was still below the 2013 level, USDA data show. That continues to be the case.

In its 2020 farm income outlook report, CRS said commodity prices had been “relatively weak” in 2019 for the “fifth-straight year,” again citing “[a]bundant domestic and international supplies of grains and oilseeds” as a contributing factor.

Separately, Hart told us the same thing.

“Agriculture has seen several years of strong, if not record, production (the last seven corn and soybean crops have been the seven largest the country has ever had, despite bad weather in some spots), good demand (but not quite good enough to avoid building stocks for some commodities), and inconsistent international trade (mainly driven by ever-changing trade policy),” Hart said in an email.

Newton gave the example of soybeans — the top U.S. agriculture export from 2014 to 2018, according to an August 2019 U.S. International Trade Commission report.

U.S. soybean farmers have been hurt by domestic and global overproduction and competition from Brazil, which has expanded its soybean crops, Newton said. In 2018, Brazil surpassed the U.S. as the top soybean producer in the world.

Then, U.S. soybean farmers were “crushed” by Trump’s trade war with China, which had been the largest export market for U.S. soybeans but reduced its purchases by 75% in 2018, the USITC report said.

“They had had several good years of really good crops in the U.S. that pushed prices lower,” Newton said. “At the same time, Brazilian production continued to grow. Then you had a weak Brazilian currency – so soybeans were already in tough position before [China] put tariffs on them.”

The Trump administration, responding to China’s retaliatory tariffs, has created programs to provide direct aid to U.S. farmers.

“Soybeans were really slammed by the tariffs, but at the same time the USDA has dumped a ton of money into the sector,” Glauber said. “Is it going to the right people? I don’t know.”

Glauber published a paper in November for the conservative American Enterprise Institute that said the administration paid an estimated total of $28 billion compensation to farmers and ranchers in 2018 and 2019. Soybean farmers received 75% of the 2018 payments, but the formula was changed in 2019 to provide more assistance to corn, wheat and cotton producers, the report said.

The bottom line: Farm bankruptcies are up, as Biden said. But the farm economy has been in what the farm bureau called a “prolonged downturn” — which predates Trump’s trade war. That economy has been “made worse by unfair retaliatory tariffs on U.S. agriculture,” as the farm bureau also says.

But none of the agricultural economists that we interviewed could say that the increase in bankruptcies was “due largely” to Trump’s trade policies.

Editor’s note: Swing State Watch is an occasional series about false and misleading political messages in key states that will help decide the 2020 presidential election.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.