Summary

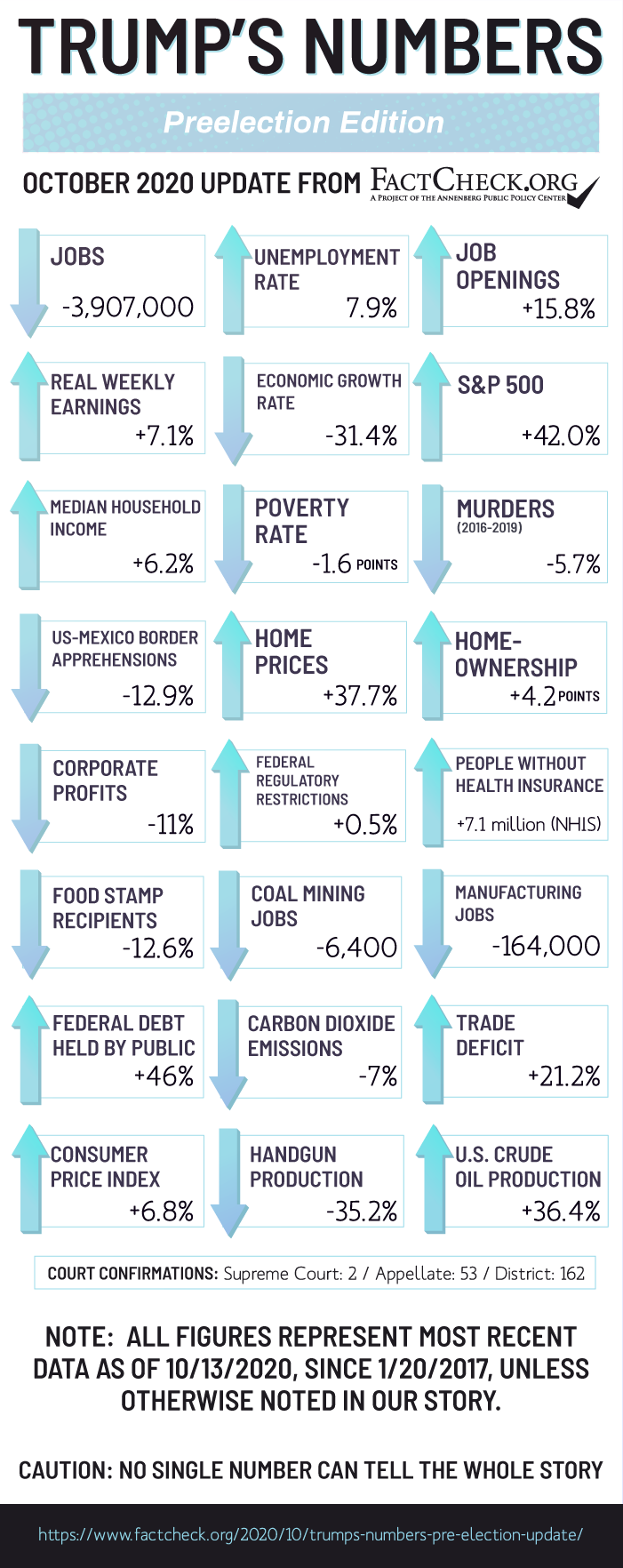

During Donald Trump’s time in office:

- The economy lost 3.9 million jobs.

- Economic growth fell short of what Trump promised, then crashed during the pandemic.

- The number of murders went down — but rebounded this year.

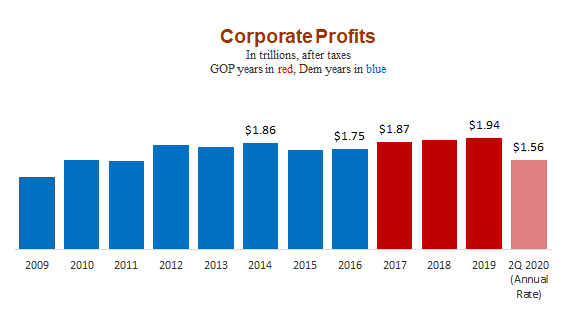

- Corporate profits set records — until this year.

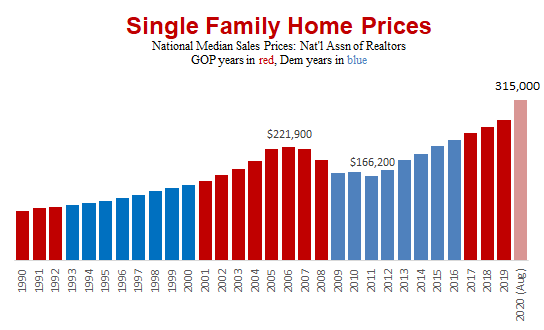

- Stock prices and home prices set records. Paychecks grew faster than prices. Poverty decreased.

- The trade deficit Trump promised to reduce grew larger instead.

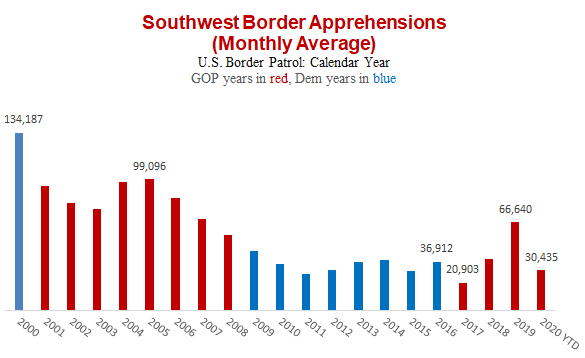

- Illegal immigration subsided, then surged, then fell back again.

- The number of people without health insurance went up by 7.1 million, according to a government survey.

- Trump installed nearly 30% of federal appellate judges and 24% of district court judges authorized by federal law.

Analysis

This is the last update before the Nov. 3 election. It’s our 11th quarterly update of the “Trump’s Numbers” scorecard that we posted in January 2018 and have updated every three months, most recently on July 17.

Here we’ve included statistics that may seem good or bad or just neutral, depending on the reader’s point of view. That’s the way we did it when we posted our first “Obama’s Numbers” article more than seven years ago — and in the quarterly updates and final summary that followed. And we’ve maintained the same practice under Trump.

Then as now, we make no judgment as to how much credit or blame any president deserves for things that happen during his time in office. Opinions differ on that.

Jobs and Unemployment

Job growth slowed a bit under Trump — then collapsed as the COVID-19 crisis led to mass unemployment. The job numbers have yet to fully recover.

Employment — After nine years and five months of constant monthly job gains — the longest such streak on record — more than 22 million jobs disappeared between mid-February and mid-April.

Just over half of those jobs (52%) were recovered in the next five months as COVID-19 restrictions eased and many businesses were allowed to reopen. The president calls this the “Great American Comeback.”

Nevertheless, as of mid-September, the most recent month on record, total employment was still 3.9 million lower than where it was when Trump took office in January 2017.

Back in 2016 Trump boasted that he would be “the greatest jobs president that God ever created.” But only 661,000 jobs were regained in September, and at that rate Trump is on pace to end his term with a net loss of employment.

Unemployment — The unemployment rate, after falling at times to the lowest rate in half a century, hit a high of 14.7% in April, by far the highest since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking the figure in 1948.

As portions of the economy have reopened, the jobless rate has turned back down. But as of mid-September the rate was 7.9% — still way above the 4.7% rate Trump inherited when he took office.

Job Openings — The COVID-19 shock ended what had been a worker shortage.

As of the last business day of August, the most recent figure on record, the number of unfilled job openings stood at just under 6.5 million — which was 15.8% more than when Trump took office.

But there were still 7.1 million more job-seekers than job openings.

The number of unfilled jobs had been as high as 7.5 million as recently as January 2019, which was the highest in the 20 years the BLS has tracked this figure. And for 23 consecutive months, starting in March 2018, the number of available jobs exceeded the number of unemployed people looking for work.

But that all came to an end soon after the White House declared a COVID-19 emergency, sending millions into unemployment.

Labor Force Participation — The unemployment rate would be even higher except for the fact that over 5 million people age 16 and over have left the labor force entirely since February, and therefore are not counted as “unemployed.” The government counts a person as unemployed only if they are out of a job despite being available for work and actively seeking a job during the most recent four weeks.

As a result of the labor-force exodus, the labor force participation rate — the portion of the entire civilian population age 16 and older that is either employed or currently looking for work in the last four weeks — dropped another 1.4 points under Trump after going down 2.9 percentage points during the Obama years.

Republicans used to criticize then-President Barack Obama for the decline during his time, even though it was due mostly to the post-World War II baby boomers reaching retirement age, and other demographic factors beyond the control of any president. Now it’s down to an even lower level, due mainly to another uncontrollable factor.

Manufacturing Jobs — Manufacturing jobs — which had increased during Trump’s first three years — took a deep dive as the virus crisis forced a wave of plant closings.

Nearly 1.4 million manufacturing jobs were lost in March and April. More than half of those (716,000) had been regained as of September.

But the net result is that 164,000 fewer people were employed in manufacturing in September compared with when Trump took office. That followed a net decrease of 192,000 under Obama.

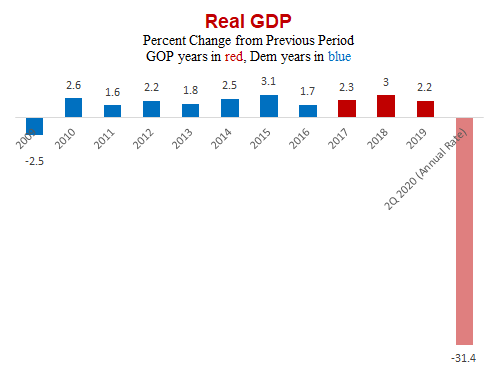

Economic Growth

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic sent the economy into a deep recession, the U.S. economy had been growing more slowly than Trump once promised.

The historical picture has changed a bit since our July update, because the Bureau of Economic Analysis revised its historical gross domestic product figures on July 30 as a result of its annual update using newly available information such as data from corporate income tax returns. Changes go back five years.

BEA now estimates that real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product grew 2.2% last year (0.1% less than its previous estimate) and 3.0% the year before (0.1% higher than previously).

Both were better than the 1.7% growth in 2016 (revised upward 0.1% from before). But now growth in Trump’s best year falls short of Obama’s best year, 2015, which was revised upward to 3.1%.

Growth under Trump has fallen well short of the 4% to 6% per year that he promised repeatedly, both when he was a candidate and also as president.

Growth halted in February as the economy entered a sudden, steep recession. In the second quarter of 2020 the economy shrank at an annual rate of 31.4%, according to the BEA.

That was by far the worst quarter since 1947, when the government began quarterly tracking of real GDP. The worst previously was the January-March quarter of 1958, when real GDP went down at a yearly rate of 10%.

The economy is now recovering as states ease COVID-19 restrictions — but slowly.

The most recent forecast of the Federal Reserve Board members and Federal Reserve Bank presidents, issued Sept. 16, produced a median estimate of a 3.7% drop in real GDP for all of 2020 (measured from fourth quarter to fourth quarter, rather than from year to year).

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office is more pessimistic. It issued an updated forecast July 2 projecting a 5.9% decline in GDP this year measured quarter to quarter (or 5.8% measured year to year). CBO said it now expects growth in the last half of this year will be even slower than it expected in May.

Income and Poverty

Household Income — Household income soared during Trump’s first three years in office, reaching a record. But Census officials cautioned that much of the increase appears to be a statistical fluke.

The Census Bureau’s published measure of median household income reached $68,703 in 2019, an apparent increase of $5,805 from 2016 after adjusting for inflation. (The median figure represents the midpoint — half of all households earned more, half less.)

In percentage terms, the apparent increase during Trump’s first three years is 9.2% — including a record 6.8% increase in 2019 alone.

But that huge 2019 jump is illusory. It’s based on a survey conducted each March, asking about the previous year’s income. But this year the survey occurred during the turmoil of a pandemic-induced partial shutdown of the economy. Census said that this year a far higher percentage of households failed to respond to the income survey than previously, and higher-income households were more likely to respond than those with lower incomes. Census said that after adjusting for this bias, “our current estimate is that income in 2019 was about 4.1% higher than in 2018.”

That’s still a healthy increase. Census put the estimated actual level of median household income last year at $66,790 — which would still be the highest level since 1967, the first year for which it published the data. And it would bring down the actual increase during Trump’s first three years to 6.2% — also still a robust figure.

Poverty — As incomes rose, the rate of poverty declined. The number and percentage of Americans living with income below the official poverty line went down — though by how much is in question.

The published Census estimate — based on the same COVID-clouded March survey as the household income figures — shows a decline of 6.6 million in the number of Americans living in poverty, and a reduction in the poverty rate of 2.2 percentage points, to 10.5% of the population.

But Census itself concedes that’s probably not right. “With the nonresponse bias correction, we estimate a poverty rate of 11.1 percent in 2019, compared to the official estimate of 10.5 percent,” Census said. That would imply 5.1 million fewer people in poverty and a reduction of 1.6 percentage points in the rate.

Regulations

The growth of federal regulation has nearly stopped under Trump.

The number of restrictive words and phrases (such as “shall,” “prohibited” or “may not”) contained in the Code of Federal Regulations stayed below 1.08 million for most of last year — a little below where it was when Trump took office. As of October 1, the count had crept up to a little above 1.08 million — an increase of 5,059 (or 0.5%) since Trump’s inauguration.

That the number has barely changed is a big departure from the past, when restrictions grew at an average of 1.5% per year during both the Obama years and the George W. Bush years, according to annual figures from the QuantGov tracking project at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center.

The Mercatus count of restrictions doesn’t attempt to assess the cost or benefit of any particular rule — such assessments require a degree of guesswork and are sensitive to assumptions. But it does track the sheer volume of federal rules with more precision than we have found in other metrics.

Some of the recent changes are just clearing deadwood. In 2018, for example, the Treasury Department scrapped an entire chapter of zombie-like regulations issued by the old Office of Thrift Supervision, which oversaw the savings and loan industry before being abolished in 2011. S&Ls have since fallen under other federal banking regulators, but the obsolete OTS rules remained on the books.

However, many of the rules Trump has eliminated are quite significant. For example, in what it called “the largest deregulatory initiative of this administration,” the Trump administration issued a final rule that nullifies Obama-era fuel economy standards for new cars and light trucks. The administration said that instead of commanding automakers to achieve average mileage of 46.7 miles per gallon by model year 2025, the Trump rule will require them to achieve only an average of 40.4 mpg.

Another example: Last year, the EPA’s Affordable Clean Energy rule took effect, repealing the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan rule. The Obama-era rule was designed to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by shifting away from coal as an energy source and would have required states to meet specific emissions reductions.

Crime

Most crime went down during Trump’s first three years in office — but murder went up last year and took a big jump in the first half of this year.

The FBI’s annual Crime in the United States report, released Sept. 28, showed the number of murders declined 5.7% during Trump’s first three years in office, despite a small 0.3% uptick in 2019. But this year the number of homicides has soared — up 14.8% during the first six months of 2020, compared with the same period in 2019, according to an FBI press release posted Sept. 15.

For comparison, the number of murders in the U.S. increased 9.6% in 2016, when Trump made it a campaign issue, and just 5.8% over the course of Obama’s entire eight years in office.

The FBI said the number of all violent crimes (murder, rape, robbery and aggravated assault) went down 3.7% during Trump’s first three years, and went down by an unspecified amount in the first six months of this year. Besides the big jump in murders in 2020, aggravated assault also increased, but the number of rapes and robberies declined.

The number of property crimes (burglary, larceny and motor vehicle theft) went down 12.6% during Trump’s first three years, and declined another 7.8% in the first half of this year, compared with the same six months a year earlier.

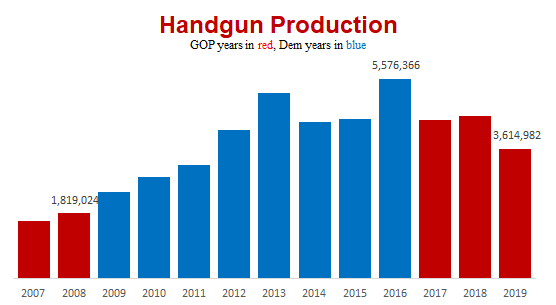

Guns

Sales and production of guns pulled back after Trump became president, but are lately surging again.

Handgun Production — In 2019, annual production of pistols and revolvers in the U.S. totaled 3.6 million, according to interim figures from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

That represented a decline of 35.2% from 2016, when production surged to a record level of nearly 5.6 million.

Handgun production more than tripled during the Obama years. So the 2019 level was still 99% higher than it had been in 2008, the last year of George W. Bush’s presidency.

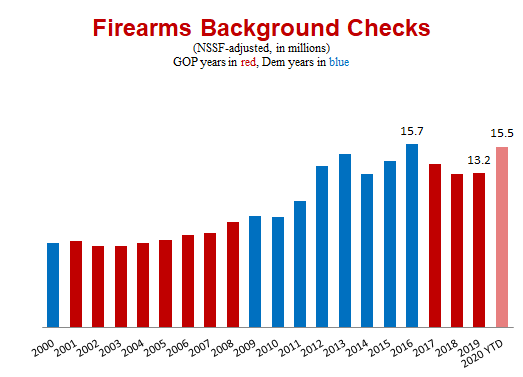

Gun Sales — Gun sales also dropped a little — until COVID-19 concerns and summer street protests set off unprecedented new waves of buying this year.

The government doesn’t collect figures on sales of guns. But the National Shooting Sports Foundation — the gun industry’s trade group — tracks approximate sales figures by adjusting FBI statistics on background checks to remove those not related to actual sales, such as checks required for concealed-carry permits.

Those NSSF-adjusted figures hit a record 15.7 million in Obama’s final year, but dropped below that during each of Trump’s first three years. This year the figure reached 15.5 million by September, so the old record seems certain to fall.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced millions of layoffs and sent many flocking to gun stores. An even bigger wave of buying took place in June, as protests over police brutality and racial injustice occurred across the country, some of them turning violent.

During the most recent 12 months on record, the NSSF-adjusted figure for background checks was 23.9% higher than the record year of 2016.

These figures cover rifles and shotguns and previously owned weapons, as well as new handguns. They are only an approximation of actual sales, since some of these checks cover purchases of multiple weapons, and of course some sales still occur without background checks.

Coal and Environment

Coal Mining Jobs — As a candidate, Trump promised to “put our [coal] miners back to work,” but he hasn’t.

As of September, there were 6,400 fewer coal mining jobs than when Trump took office, according to BLS figures. That’s a decline of nearly 13%.

The coronavirus pandemic may have hastened some of the losses, but, in fact, nearly 600 mining jobs were lost last year — long before the virus appeared in China — when two Wyoming mines closed and the owner filed for bankruptcy protection. And Moody’s Investor Services said it had been predicting a 15% to 20% decline in U.S. coal production this year even before the virus hit.

U.S. coal production last year was the lowest in 41 years — and it’s headed much lower this year. During the 12 months ending in August (the most recent month for which figures are available), the Energy Information Administration estimated that 579 million short tons were produced, which is 21% below the figure for 2016.

In October, EIA predicted that coal production would fall 26% in 2020, citing the pandemic and also lower natural gas prices as factors.

Carbon Emissions — Carbon dioxide emissions from energy consumption declined under Trump, continuing a long downward trend that started years before he took office.

Figures from EIA show CO2 emissions were 7.0% lower in the most recent 12 months on record, ending in June, than they were in 2016. Much of the decline is due to the pandemic-induced recession. Emissions in March, April, May and June were running nearly 20% below the same four months in 2019.

In the decade before Trump took office, emissions had already fallen by a total of 14%, due mainly to electric utilities shifting away from coal-fired plants in favor of cheaper, cleaner natural gas, as well as solar and wind power.

EIA is currently estimating that CO2 emissions will fall by a record 10% for all of 2020.

Border Security

Illegal border crossings have subsided after surging last year to the highest in a dozen years. They are now running a bit lower than before Trump took office.

Last year, a monthly average of 66,640 people were apprehended attempting to illegally enter the U.S. at the border with Mexico, the highest level since 2007.

The peak month was May, which saw 132,856 apprehensions, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection statistics. That was the highest total since March 2006, when the monthly total hit nearly 161,000.

During the first eight months of 2020, the average has gone down to 30,435 per month.

Attempted border crossings tend to be highest in March, April and May and lowest in December. So to even out that seasonal factor, our measure compares the most recent 12 months on record with the year prior to a president taking office. And for the past 12 months ending in August (the most recent for which figures are available) apprehensions totaled 385,774, just 12.9% below 2016, when the total was 442,940.

Corporate Profits

After-tax corporate profits set new records during Trump’s presidency — until taking a battering during this year’s pandemic.

Newly revised figures now show profits hit a record $1.90 trillion in 2018 (see line 45), and yet another record — $1.94 trillion — last year. But in the recessionary second quarter of this year they sank to an estimated annual rate of $1.56 trillion.

That’s 11% lower than the full-year figure for 2016, the year before Trump’s inauguration.

Stock Market

The pandemic has been a disaster for the economy — but not for the stock market.

A plunge in stock prices in March ended a decade-long bull market and wiped out nearly all the gains of the Trump years. But that quickly turned out to be the shortest bear market in history.

The Standard & Poor’s 500-stock average has since set new record highs. It closed most recently on October 13 at 55.1% above where it had been the day before Trump was inaugurated.

Other indexes also reflected investor optimism. At the October 13 close, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, made up of 30 large corporations, was up 45.3% during Trump’s time in office.

And the NASDAQ composite index, made up of more than 3,000 companies including many in the technology sector, has more than doubled under Trump — up 114.1% since he took office.

Wages and Inflation

The upward trend in real wages continued under Trump, and inflation remained in check.

CPI — The Consumer Price Index rose 6.8% during Trump’s first 44 months, continuing a long period of historically low inflation.

In the most recent 12 months, ending in March, the CPI rose only 1.4% — held down by a plunge in gasoline prices and the pandemic-triggered economic recession. The CPI rose an average of 1.8% each year of the Obama presidency (measured as the 12-month change ending each January), and an average of 2.4% during each of the George W. Bush years.

Wages — Paychecks continued to grow faster than prices.

The average weekly earnings of all private-sector workers, in “real” (inflation-adjusted) terms, rose 7.1% during Trump’s first 44 months (ending in September).

Those figures include managers and supervisors. Rank-and-file production and nonsupervisory workers — at least, those who still have jobs — are doing even better than their bosses. Real earnings for those workers (81% of all workers) have gone up 8% so far under Trump.

The gains extend a long trend. Real wages took a dive during the Great Recession of 2007-2009, hitting a low point in July 2008. During the Obama years, real weekly earnings rose 4.1% for all workers, and 4.2% for rank-and-file.

Consumer Sentiment

Consumer confidence in the economy, which at first rose under Trump, took its worst plunge on record when the COVID-19 emergency hit.

The University of Michigan’s Surveys of Consumers monthly index first soared to a peak of 101.4 in March 2018, which was the highest in 14 years. It was still at 101.0 as recently as February.

But in March and April, it took the steepest decline ever recorded, to 71.8. That was the lowest since December 2011, when the nation was struggling to recover from the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

By September — the most recent month on record — the index had crept up to 80.4. But that was still 6.8 points lower than in October 2016, just before Trump was elected after promising to boost economic growth.

Home Prices and Ownership

Home Prices — Home prices soared to record levels during Trump’s tenure.

The national median price of an existing, single-family home set a record high of $315,000 in August, according to sales figures from the National Association of Realtors.

That is $86,300 higher than the median price of $228,700 for homes sold during the month Trump took office — a gain in value of 37.7%. That far outpaced inflation; the Consumer Price Index rose only 6.6% during the same period.

Much of the rise has taken place since the pandemic hit. Single-family home prices jumped 15.5% since February.

The Realtors’ figures reflect raw sales prices without attempting to adjust for such factors as variations in the size, location, age or condition of the homes sold in a given month or year. Even so, a similar pattern emerges from the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index, which compares sales prices of similar homes and seeks to measure changes in the total value of all existing single-family housing stock.

The Case-Shiller index for July sales (the most recent available) was at a record high — and 20% above where it stood in the month Trump took office.

Whichever way you measure it, homeowners have seen the value of their houses rise to record levels since Trump became president.

Homeownership — The percentage of Americans who own their homes has continued to recover under Trump.

The homeownership rate hit a record 69.2% of households for two quarters in 2004 before going into a yearslong slide and hitting bottom in the second quarter of 2016 at 62.9%. That was the lowest point in more than half a century, and tied for the lowest on record.

The rate recovered 0.8 points in the six months before Trump took office, and has gone up another 4.2 points since then, to 67.9% in the second quarter of 2020, the most recent Census Bureau figure available.

However, much of that gain is another statistical distortion caused by the pandemic. The reported figure took an unlikely 2.6 percentage point leap in the second quarter alone, nearly triple the largest previous quarter-to-quarter increase (0.9 point in the third quarter of 1979). Realtor’s association economists expressed “serious questions” about the most recent figure’s accuracy, and Census urged “caution” in comparing it to past quarters. Because of the pandemic, Census used telephone interviews rather than in-person interviews during the survey, resulting in a very low response rate.

Trade

The trade deficit that Trump promised to reduce grew larger instead. It fell a bit last year but is rising again this year.

The most recent government figures show that the total U.S. trade deficit in goods and services during the most recent 12 months on record (ending in July) was over $583 billion, an increase of 21.2% over the deficit for 2016.

The deficit seemed to stabilize in 2019, falling 0.5% compared with the previous year, after rising 11.4% in 2018 and 6.3% in 2017, Trump’s first year in office.

But the deficit resumed its rise in 2020, going up 1.8% during the first seven months of the year, compared with the same period a year earlier.

China — The goods-and-services trade deficit with China has finally grown smaller under Trump.

Trump began a full-scale trade conflict with China in early 2018. At first the trade gap with China continued to go up, but that turned around in 2019, when the US-China trade gap went down 19% compared with the previous year. During the most recent 12 months on record (ending in July), the gap was 11.9% lower than the year before Trump took office, according to BEA’s figures.

The trade war continues. Trump signed a “phase one” trade deal with China on Jan. 15, under which the U.S. held off on new tariffs while China promised to buy more U.S. agricultural goods. But China is far behind the pace it promised. As of July, it had increased purchases of U.S. goods at less than half the pace needed to meet the agreed targets, according to tracking published by the Peterson Institute. Furthermore, China has yet to agree to reduce subsidies to exporting businesses or to limit its demands that U.S. businesses share their intellectual property.

Mexico — Meanwhile the trade deficit in goods and services with Mexico has grown much faster than the global trade gap. It totaled $96 billion during the most recent 12 months, an increase of 50% compared with 2016.

Canada — The trade surplus that the U.S. runs with Canada has turned into a deficit. In 2016, the U.S. sold nearly $10.9 billion more to Canada in goods and services than Canada bought from the U.S. That flipped last year, when the U.S. imported $2.7 billion more from Canada than the other way around. For the most recent 12 months on record the gap widened to $4.4 billion.

On March 13, Canada gave final legislative approval of a new trade agreement with the U.S. and Mexico, to replace the 26-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement, which Trump had promised to scrap during his campaign. The agreement finally took full effect July 1.

Health Insurance Coverage

Millions of Americans lost health insurance under Trump.

The latest figures from the National Health Interview Survey, posted on Sept. 9, put the number of people who lacked coverage in the last six months of 2019 at 35.7 million — an increase of 7.1 million since 2016, the year before Trump took office.

Most of the increase — 5 million — occurred between the first six months of last year and the last half. The NHIS interviews people throughout the year.

Trump failed to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act as he promised to do, but did slash advertising and outreach aimed at enrolling people in Obamacare plans. In December 2017, he signed a tax bill that ended the ACA’s tax penalty for people who fail to obtain coverage, effective last year. In March 2019, the Trump administration joined an effort by GOP state attorneys general seeking a court decision to overturn the entire act. And on June 25 the administration formally asked the Supreme Court to strike down Obamacare. The high court is expected to hear the case in November.

Food Stamps

The number of food stamp recipients dropped to the lowest levels in a decade — but is rising again since the COVID-19 recession hit.

But just how high, the government isn’t yet saying.

As we reported in our last update, the number of recipients rose by nearly 480,000 in March, to 37.3 million or 12.6% below where it stood when Trump took office.

The number almost certainly shot up from there as the unemployment rate surged and Congress loosened eligibility standards as part of an emergency relief bill. Benefit levels have also increased 40%, making the program more attractive.

Normally figures for April, May and June would be posted by now, but so far none have appeared. When we inquired, the administrator of the Food and Nutrition Service, Pam Miller, issued a statement saying the agency “has identified significant issues with the accuracy of state-reported data in recent months due to COVID-19-related complexities. Therefore, reliable program data are not available at this time.” She didn’t say when data would be made public.

Judiciary Appointments

Trump is putting his mark on the federal appeals courts more quickly than Obama was able to do in his time in office.

Supreme Court — So far, Trump has won Senate confirmation for two Supreme Court nominees, Justice Neil M. Gorsuch and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh. But if his nominee Amy Coney Barrett is confirmed by the Republican-led Senate as expected, he will have filled one-third of all seats on the high court during his term.

Obama was able to fill only two high court vacancies during his first term (and as it turned out, during his entire eight years in office) — with Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Justice Elena Kagan.

Court of Appeals — Trump also won confirmation of 53 U.S. Court of Appeals judges (30 during his first two years and another 23 in 2019 and so far in 2020). That’s far more than the total for Obama, who won confirmation for 30 as of the same point in his first term (16 during his first two years and 14 more in 2011 and through this date in 2012).

Trump has now installed nearly 30% of all the 179 appellate court judges authorized by federal law.

District Court — Trump also outpaced Obama on filling lower courts, though by a smaller margin. So far, Trump has won confirmation for 162 of his nominees to be federal District Court judges. That’s nearly 24% of the 677 authorized district judges. Obama had won confirmation for 130 at the same point in his presidency.

Trump also has filled six seats on the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which has nationwide jurisdiction over lawsuits seeking money from the government. And he has filled two seats on the U.S. Court for International Trade. Obama filled none to either court during his first term.

Trump must share responsibility for this record with the Republican majority in the Senate. Republicans not only refused to consider Obama’s appointment of Merrick Garland to fill the Supreme Court vacancy eventually filled by Gorsuch, but they also blocked confirmation of dozens of Obama’s nominees to lower courts. Trump inherited 17 Court of Appeals vacancies, for example, including seven that had Obama nominees pending but never confirmed.

Federal Debt and Deficits

The federal debt has increased by over $6.6 trillion under Trump. And the rise is continuing as the government borrows frantically to fund emergency COVID-19 spending.

The federal debt held by the public stood at over $21 trillion at the last count on Oct. 8 — 46% higher than on the day he took office.

The figure is certain to rise even more as tax revenues fall due to the partial shutdown of the economy, and spending ramps up to aid jobless workers and shuttered businesses.

But even before the COVID-19 emergency, Trump’s cuts in corporate and individual income tax rates — as well as bipartisan spending deals he signed in 2018 and 2019 — caused the red ink to gush faster than it did before.

The federal government’s annual deficit soared to about $3.1 trillion during the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, the CBO estimates. (The final, official tally by the U.S. Treasury Department is still being processed.) That’s double the previous record yearly deficit of $1.55 trillion, set in fiscal year 2009.

CBO estimates that the debt in the fiscal year that just ended equaled 98% of the nation’s entire gross domestic product, highest since 1948. And it’s on track to grow to over 104% of GDP in the current fiscal year, CBO estimates. The record is 106% of GDP in 1946, at the end of World War II.

Oil Production and Imports

U.S. crude oil production resumed its upward trend under Trump, hitting record levels. Production topped 4 billion barrels in 2018 for the first time on record, and kept on rising. In the 12 months ending in July (the most recent data available), it reached over 4.4 billion barrels, a 36.4% increase compared with all of 2016.

A lot of wells stopped pumping when oil prices crashed briefly due to the pandemic shutting down much travel and business activity. U.S. production plunged 21% during April and May but then bounced back nearly 10% in June and July, and is expected to stabilize.

With production at such a high level, the nation’s dependence on imported petroleum at last disappeared.

Dependence on foreign oil peaked in 2005, when the U.S. imported 60.3% of its petroleum. But the U.S. became a net exporter last September, and in nearly every month since, according to Energy Information Administration figures. During the first eight months of 2020, the U.S. produced enough oil to supply all its domestic needs and exported another 2.2% in surplus oil and petroleum products, EIA estimated.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Sources

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National); Total Nonfarm Employment, Seasonally Adjusted.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; Unemployment Rate, Seasonally Adjusted.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey: Job Openings, Seasonally Adjusted.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; Labor Force Participation Rate.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; Unemployment Level, Seasonally Adjusted.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; All employees, thousands, manufacturing, seasonally adjusted.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

National Bureau of Economic Research. “Determination of the February 2020 Peak in US Economic Activity.” 8 Jun 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “The 2020 Annual Update of the National Income and Product Accounts.” Survey of Current Business. Aug 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Table 1.1.1. Percent Change From Preceding Period in Real Gross Domestic Product.” Interactive data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Current Population Survey, 1966 to 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplements.” 10 Sep 2019.

McLaughlin, Patrick A., and Oliver Sherouse. RegData U.S. Regulation Tracker. QuantGov, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA. Downloaded 13 Oct 2020.

McLaughlin, Patrick A. and Oliver Sherouse. RegData US 3.1 Annual (dataset). QuantGov, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA. “RegData 3.1 Annual Summary.” Downloaded 13 Oct 2020.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. “Crime in the United States 2019,” Table 1. 28 Sep 2020.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. “Overview of Preliminary Uniform Crime Report, January–June, 2020.” 15 Sep 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “Annual Firearms Manufacturing and Export Report, Year 2019 Interim.” 7 Jul 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “Annual Firearms Manufacturing and Export Report, Year 2016 Final.” 4 Jan 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “Annual Firearms Manufacturing and Export Report, Year 2008 Final.” 8 Mar 2011.

National Shooting Sports Foundation. “National Shooting Sports Foundation® Report: NSSF-Adjusted NICS – Historical Monthly Chart.” Proprietary data supplied on request and posted with NSSF permission. 5 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey; All employees, thousands, coal mining, seasonally adjusted.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Table 6.1 Coal Overview.” Online data from Monthly Energy Review. 24 Sep 2020.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. Short Term Energy Outlook. 6 Oct 2020.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Monthly Energy Review: Table 11.1 Carbon Dioxide Emissions From Energy Consumption by Source.” 24 Sep 2020.

U.S. Border Patrol. “U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions FY 2020.” 7 Oct 2020.

U.S. Border Patrol. “Total Illegal Alien Apprehensions By Month Fiscal Years 2000-2018.” Undated. Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Corporate Profits After Tax (without IVA and CCAdj) (CP), retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Line 45. “National Income and Products Accounts, Table 1.12. National Income by Type of Income, Annual.” 25 Jun 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “National Income and Products Accounts, Table 1.12. National Income by Type of Income, Quarterly.” 30 Sep 2020.

Egan, Matt. “The bull market turns 10 years old.” CNN Business. 11 Mar 2019.

Menton, Jessica and Nathan Bomey. “Dow endures worst day since ‘Black Monday’; S&P 500 enters bear market as coronavirus spreads economic gloom.” 12 Mar 2020.

Yahoo! Finance. “Dow Jones Industrial Average.” Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Yahoo! Finance. “S&P 500.” Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Yahoo! Finance. “NASDAQ Composite.” Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Consumer Price Index – All Urban Consumers.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National); Average Weekly Earnings of All Employees, 1982-1984 Dollars.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment, Hours, and Earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey (National); Average Weekly Earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, 1982-1984 Dollars.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers. “The Index of Consumer Sentiment.” 2 Oct 2020.

National Association of Realtors. “Sales Price of Existing Single-Family Homes.” 22 Sep 2020.

S&P Dow Jones Indices. “S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price NSA Index.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Time Series: Not Seasonally Adjusted Home Ownership Rate.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services, August 2020.” 6 Oct 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Table 1, U.S. Trade in Goods and Services, 1992-present.” 6 Oct 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Table 3. U.S. International Trade by Selected Countries and Areas: Balance on Goods and Services.” 6 Oct 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Health Interview Survey. “Health Insurance Coverage: Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, 2019.“ 9 Sep 2020.

Kliff, Sarah. “Trump is slashing Obamacare’s advertising budget by 90%.” Vox.com. 31 Aug 2017.

Lee, MJ et al. “GOP Obamacare repeal bill fails in dramatic late-night vote.” CNN.com. 28 Jul 2017.

Mukherjee, Sy. “The GOP Tax Bill Repeals Obamacare’s Individual Mandate. Here’s What That Means for You.” Fortune. 20 Dec 2017.

Haberman, Maggie and Robert Pear. “Trump Sided With Mulvaney in Push to Nullify Health Law.” The New York Times. 27 Mar 2019.

Texas v U.S. (5th Cir. 2020)

Luthi, Susannah. “Trump administration asks Supreme Court to overturn Obamacare.” Politico.com. 25 Jun 2020.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (Data as of June 12 2020).” 16 Jul 2020.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) data, FY 69 through FY18 National View Summary. ZIP Excel files. Accessed 16 Jul 2020.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. “FNS Response to COVID-19” Website, accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “Judicial Confirmations for January 2019,” archived web listing of confirmations in 115th Congress. Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “Confirmation Listing” web listing of confirmations in 116th Congress. Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “Judicial Confirmations for January 2011,” archived web listing of confirmations in 110th Congress. Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “Judicial Confirmations for January 2013,” archived web listing of confirmations in 111th Congress. Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Treasury. “Debt to the Penny.” Data extracted 13 Oct 2020

Congressional Budget Office. Monthly Budget Review for September 2020. 8 Oct 2020.

Office of Management and Budget. Historical Tables: “Table 1.1 – SUMMARY OF RECEIPTS, OUTLAYS, AND SURPLUSES OR DEFICITS ( – ): 1789 – 2025” Undated.

Congressional Budget Office. “An Update to the Budget Outlook: 2020 to 2030.” 2 Sep 2020.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “U.S. Field Production of Crude Oil.” Accessed 13 Oct 2020.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Table 3.3a Petroleum Trade: Overview.” Monthly Energy Review. Accessed 13 Oct 2020.