SciCheck Digest

There is no evidence that vaccines could cause harm to people who already have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or have become ill with the disease COVID-19. On the contrary, recent studies show the vaccine gives an important immunity boost to those previously infected and suggest that one dose might be enough.

Full Story

Update, Aug. 23, 2021: The Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, which was previously authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use, received full approval from the agency on Aug. 23 for people 16 years of age and older.

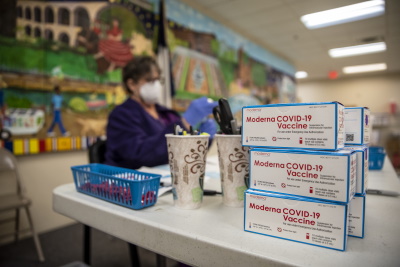

Update, Feb. 10, 2022: The Moderna COVID-19 vaccine received full approval from the FDA on Jan. 31 for individuals 18 years of age and older.

The authorized COVID-19 vaccines have been found to be safe and effective in clinical trials and in real-world conditions. Out of more than 220 million doses administered so far and clinical trials with thousands of participants, there is no evidence showing that vaccinating those with previous SARS-CoV-2 infections could be unsafe.

On the contrary, increasingly growing evidence shows one dose of the vaccine benefits individuals who’ve recovered from the infection, boosting their immune response and providing them with full protection for a period of time.

On the contrary, increasingly growing evidence shows one dose of the vaccine benefits individuals who’ve recovered from the infection, boosting their immune response and providing them with full protection for a period of time.

“Our study and several other studies show that there is a benefit, immunologically … in people who were previously infected,” E. John Wherry, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Immunology, told FactCheck.org in a phone interview.

Yet a number of viral posts question the need of vaccinating those who’ve already recovered from COVID-19, and one of them, published by Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s anti-vaccination organization, falsely claims it “could potentially cause harm, or even death.”

Researchers told FactCheck.org that is not what the evidence is showing.

“There’s no indication that vaccinating people who had previously had COVID is resulting in an increased risk of adverse events,” Wherry said.

Wherry, who is one of the lead authors of a study looking at the immune responses to the mRNA vaccines in individuals with and without previous infections, said people who recover from the disease show different levels of antibodies created by the immune system to identify and neutralize the virus. The vaccines, he said, improved the immune response in individuals by raising the levels of neutralizing antibodies in those who’ve been infected.

“Some people actually have fairly low antibody responses that are not sufficient to neutralize the virus, especially variant viruses. When you vaccinate them uniformly, you get high antibody titers [measurements] and high neutralization titers, so there’s an improvement in at least one of the key metrics of immunity following vaccination,” he said.

According to guidance by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people who’ve already had COVID-19 should be vaccinated anyway because “experts do not yet know how long” they are protected from getting sick again. Those who’ve gotten the disease get some protection by building what’s called natural immunity. And although available evidence shows that reinfection is uncommon in the months following the first infection, the CDC says that may vary over time.

“Available data suggest that previously infected individuals can be at risk of COVID-19 (i.e., reinfection) and could benefit from vaccination. Furthermore, data suggest that the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines in previously infected individuals is just as favorable as in previously uninfected individuals,” a spokesperson for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration told us in an email.

Up until now, the passive and active surveillance systems set up to monitor the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines have only found rare adverse events associated with the vaccines.

A small number of people (2 to 5 people per million vaccinated) have reported a severe allergic reaction called anaphylaxis. And the CDC and the FDA are studying a small number of cases of people who experienced a rare and severe type of blood clot with low platelets after getting the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. As a result, the agencies recommended a pause in the use of this product. On April 23, a CDC panel of advisers recommended the pause be lifted.

No Evidence of Risk for Previously Infected Individuals

In a blog post on The Defender, a website owned by R.F.K. Jr.’s organization, Children’s Health Defense, a freelance reporter writes that there’s no science supporting the need of vaccinating people who have recovered from COVID-19. “There’s a potential risk of harm, including death, in vaccinating those who’ve already had the disease or were recently infected,” the post claimed.

Researchers don’t agree, including one quoted by The Defender.

Dr. Colleen Kelley, an associate professor of medicine and epidemiology at Emory University School of Medicine and the principal investigator for Moderna’s and Novavax’s phase 3 vaccine trials at Emory, is quoted by The Defender as saying people with previous infection get “harsher side effects” after vaccination. Her remarks came from a HuffPost article in March.

In a phone interview, Kelley told us that tolerable side effects are expected, and not always present. In the Moderna trials, “there did not appear to be an increased rate of side effects among people who were antibody positive when they were vaccinated,” she said.

“There is absolutely no evidence that there is any harm for people to be vaccinated, who have previously had COVID disease,” Kelley said.

The Defender’s claims are mostly based on statements by Dr. Hooman Noorchashm, a former assistant professor of surgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, who has been warning health officials, vaccine manufacturers and more recently university leaders of the potential danger of vaccinating people who have recently been infected with the novel coronavirus.

Noorchashm has been voicing his arguments widely, including on Fox News’ “Tucker Carlson Today“ and The Defender podcast. But he admits they are based on “a ‘prognostication’ in that I have put it forth in the absence of clear ‘evidence’ of it being a material risk.”

Based on previous studies not related to the COVID-19 pandemic, Noorchashm argues that antigens of SARS-CoV-2 remain in the tissues of someone who’s been infected for some time after they’ve recovered. The vaccine, he says, reactivates the immune response, targeting the tissues where these antigens remain, causing further inflammation and damage, including to the vascular endothelium, the thin tissue that lines the heart and blood vessels.

“Most pertinently, when viral antigens are present in the vascular endothelium or other layers of the blood vessel, and especially in elderly and frail with cardiovascular disease, the antigen specific immune response incited by the vaccine is almost certain to do damage to the vascular endothelium,” he said in a Jan. 26 letter sent to FDA officials and Pfizer executives. “Such vaccine directed endothelial damage is certain to cause blood clot formation with the potential for major thromboembolic complications, at least in a subset of such patients.”

In a phone interview with FactCheck.org, Noorchashm explained that all medical treatments, including vaccines, have some complications. And if those complications happen when a treatment is avoidable — in this case, he says, vaccinating those who’ve recently been infected — then that’s potentially harmful.

His recommendation is to test people’s antibodies before vaccination and to delay vaccination for approximately eight months after infection. He and his wife, a physician who died in 2017, fought for years to ban a tool used to remove uterine fibroids, after the procedure spread cancer into his wife’s abdomen.

Dr. Steven Varga, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Iowa whose lab studies immunopathology in respiratory virus infections, told us he’s not aware of any scientific data that demonstrates that viral antigens persist long after the SARS-CoV-2 infection has gone away. And if there were, he says, there would likely be insufficient levels to drive such a robust immune response to cause the damage Noorchashm suggests.

“Generally, once the virus is cleared, there can be some viral antigen that persists in various locations, so it is possible there could be some in the endothelium,” Varga said. “Again, I’m not aware of any studies that have shown that to be the case. But even if there were small amounts of viral antigen, generally that shouldn’t be enough viral antigen to induce the type of damage that would need to occur to have the kind of more severe outcome.”

Dr. Donna Farber, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University focused on immunological memory, told us Noorchashm’s prognostication is not consistent with the data.

“The data are that the virus is cleared from the lungs, the virus is cleared from the upper respiratory tract. And so if there’s no virus, there’s no antigen,” Farber, who recently published a study on the immune response to COVID-19 in the lungs, said in a phone interview.

Farber added that the protective immunity provided by the vaccine, neutralizing antibodies, do not cause the sort of harm Noorchashm is talking about. That could happen, she says as an example, if there was a virus hidden in cells and then a patient is given cytotoxic T cells, a type of immune cell that can kill infected cells or cancer cells.

“But the chance of that happening in a vaccine — and for a vaccine that’s really targeting neutralizing antibodies and not, you know, the sort of a killer T cell response — it’s just inconsistent with the science,” she said.

Farber also said for most pathogens, our immune system requires repeated exposure to get protection over time. That’s why people get a vaccine for influenza every year, she said, regardless if they’ve been exposed to the virus or not.

“Seeing an antigen again and again, isn’t bad for you. It’s what we do all the time. And it’s what our immune system has evolved to do. And that’s how it generates its best memory,” she said.

Benefits of Vaccine on Previously Infected Individuals

According to The Defender’s post, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices issued a report “that falsely claimed a Pfizer study proved the vaccine was highly effective” for people with previous infections.

Rep. Thomas Massie, a Kentucky Republican, “found that vaccine studies showed no benefit to people who had coronavirus and that getting vaccinated didn’t change their odds of getting reinfected” and asked the CDC to fix the mistake in the report, The Defender said.

The CDC added an erratum to the report on Jan. 29, but it merely mentions that consistent high efficacy was found “in a secondary analysis including participants both with or without evidence of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

The report shows that in the Pfizer/BioNTech clinical trials the vaccine was 94% effective and “when you look at both groups together, the data suggest the vaccine works well in both groups,” CDC spokesperson Kristen Nordlung told us. It also showed, Nordlung added, that those who had COVID-19 can still be at risk of reinfection and could benefit from the vaccine, not be harmed by it.

As we’ve explained, scientific studies do show benefits for those who’ve recovered from the infections.

A recent study published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine journal found that a prior infection with SARS-CoV-2 does not completely protect young people against reinfection. The study observed over 3,000 healthy U.S. Marine Corps recruits, 18 to 20 years old, from May to November 2020. The study found that around 10% of the participants who were previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 became reinfected. In comparison, 48% of those without previous infection became infected.

A different observational study was done in Denmark using data from approximately 10 million polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, tests during two surges last year, from March to May 2020 and from September to December. According to their analysis a previous infection provided about 80-83% protection against a second infection in people younger than 65 years old and 47% for those aged 65 years and older.

According to a CDC study, both Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines reduced the risk of infection, in real-world conditions, by 90% two weeks after the second dose.

In addition, it has been reported that the vaccine may actually be helping people with previous infections and long-lasting symptoms, what’s been called “long COVID.”

When asked about other studies supporting Rep. Massie’s statements, his office sent us an FDA presentation and an FDA memo reviewing the efficacy and safety of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Both show high general efficacy and the second specifically mentions that since the clinical trial didn’t include many people with prior infection “available data are insufficient to make conclusions about benefit in individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

John Kennedy, Massie’s communications director, told us the congressman didn’t say whether the vaccine can be dangerous for those with previous infections. In fact, Kennedy said, “Congressman Massie believes that the Pfizer and Moderna trials he commented on didn’t really demonstrate higher rates of adverse reaction for those with prior infection.”

Update, Aug. 10: A CDC retrospective study in Kentucky found unvaccinated residents who were infected with the coronavirus in 2020 had a 2.34 times higher risk of being reinfected in May and June 2021, compared with those who were fully vaccinated. In the Aug. 6 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC concluded: “To reduce their likelihood for future infection, all eligible persons should be offered COVID-19 vaccine, even those with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

The case-control study looked at adult Kentucky residents who had confirmed positive COVID-19 test results from March through December 2020, according to a state database. It then identified case-patients who had a subsequent positive COVID-19 test from May 1 through June 30, 2021. A control group included residents who had been infected in 2020 and weren’t reinfected in the May through June time frame. The study matched 246 case-patients to 492 control individuals on a 1:2 ratio based on age, sex and date of the first positive test. Vaccination data from the Kentucky Immunization Registry showed 20.3% of case-patients and 34.3% of controls were fully vaccinated.

“The findings from this study suggest that among previously infected persons, full vaccination is associated with reduced likelihood of reinfection, and, conversely, being unvaccinated is associated with higher likelihood of being reinfected,” the CDC said.

The agency cautioned that the study was based on one state and a short reinfection time period, meaning the “findings cannot be used to infer causation,” and that larger studies are needed.

Vaccination After Infection: How Long to Wait?

Although the CDC once recommended that those recovering from COVID-19 wait 90 days before receiving a vaccine, that advice now only applies to those who were treated with monoclonal antibodies or convalescent plasma.

“While there is no recommended minimum interval between infection and vaccination, current evidence suggests that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection is low in the months after initial infection but may increase with time due to waning immunity,” CDC’s interim clinical considerations for use of the vaccines say. “Thus, while vaccine supply remains limited, people with recent documented acute SARS-CoV-2 infection may choose to temporarily delay vaccination, if desired, recognizing that the risk of reinfection and, therefore, the need for vaccination, might increase with time following initial infection.”

Experts interviewed for this story agreed that those recovering from COVID-19 or an infection should wait somewhere between three weeks and 90 days to get vaccinated. But that’s because that would ensure a better immune response, not because it could be dangerous.

“Usually you want to wait a month for the immune response to die down a little bit and for you to get back to baseline, because if you’re back to baseline, you’ll respond better to vaccines,” Farber said.

Varga added it is best to give the immune system some time to build memory cells, which would improve its response the next time the body sees the antigen.

“You would get a lower antibody response and T cell response if you got vaccinated, you know, just a very short time frame after recovering, versus if it was, you know, three or four weeks ago,” he said.

Vaccination After Infection: One or Two Doses?

The FDA issued its emergency use authorization to the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines based on the safety and efficacy evidence provided by clinical trials using two doses of the vaccine.

“Individuals who have received one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine should receive a second dose on schedule to complete the vaccination series,” said an FDA spokesperson.

But a number of recent studies, including some which have not yet been peer-reviewed, show that only one dose could be enough for those previously infected to be fully protected against SARS-CoV-2 and some of its variants.

One of them, published by a team from the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine in Science Immunology, found that in individuals who recovered from the infection, the first vaccine dose “significantly boosted” antibody and memory B cell responses, but a second dose did not increase “circulating antibodies, neutralizing titers or antigen-specific memory B cells.”

The study was relatively small — 44 healthy individuals, including 11 who had a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection — but it was the first study to look at memory B cells, which provide long-term immunity, in addition to antibodies, which provide immediate response.

Another study published as a preprint on medRxiv by a research team led by Florian Krammer and Viviana Simon from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, recruited 109 participants, including 41 with previous infections. The study showed that the immune response to the first dose of the vaccine for those previously infected was equal, and sometimes stronger, than the response to the second for those who had never had SARS-CoV-2.

None of these eight studies described harmful effects of vaccination, either with one or two doses, on participants who had suffered a previous infection. The Mount Sinai study found that those already primed with the infection showed a stronger immune response (sore arm, fever, chills, fatigue) to the first dose of the vaccine. But Wherry, one of the lead authors of the Penn study, said their study observed no increase in circulating antibodies after the second dose.

“We did not see any harm from the second dose, we just didn’t see any benefit,” Wherry said.

Is one vaccine dose enough then?

Maybe, according to the National Institutes of Health Director Dr. Francis Collins, if other studies support these results and FDA and CDC expert advisors agree. In a blog, Collins wrote that such a policy is under consideration in France and, if implemented, it could extend global vaccine supply and speed up the vaccination process.

“While much more research is needed—and I am definitely not suggesting a change in the current recommendations right now—the results raise the possibility that one dose might be enough for someone who’s been infected with SARS-CoV-2 and already generated antibodies against the virus,” he wrote.

An FDA spokesperson said studies “are currently being conducted to evaluate whether one dose is sufficient” for those with previous infections.

Wherry said larger studies are needed, specifically some looking at protection. So far, all of the studies are looking at immunological events, but none of them have studied how well one dose could protect someone in the real world.

“I’m reluctant to change policy based on immunological data alone. I’d want to see actual efficacy of one dose versus two doses. And that’s gonna be very hard to do in the real world,” Wherry said.

Clarification, April 27: Although nothing in the article indicates that Dr. Noorchashm is a member of an anti-vaccination group, Dr. Noorchashm requested that we add that he is not anti-vaccine. He said he has been vaccinated against COVID-19.

Correction, June 30: We corrected the name of the journal Science Immunology. We originally called it Science Immunologist.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s COVID-19/Vaccination Project is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over our editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation. The goal of the project is to increase exposure to accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines, while decreasing the impact of misinformation.

Sources

“COVID Data Tracker.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Last updated 22 Apr 2021, accessed 22 Apr 2021.

Krammer, Florian, et al. “Antibody Responses in Seropositive Persons after a Single Dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine.” New England Journal of Medicine. 10 Mar 2021.

Stamatatos, Leonidas, et al. “mRNA vaccination boosts cross-variant neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection.” Science. 25 Mar 2021.

Goel, Richi R., et al. “Distinct antibody and memory B cell responses in SARS-CoV-2 naïve and recovered individuals following mRNA vaccination.” Science Immunology. Vol. 6. Issue 58. 15 Apr 2021.

Samanovic, Marie I., et al. “Poor antigen-specific responses to the second BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine dose in SARS-CoV-2-experienced individuals.” medRxiv. Feb 9 2021.

Krammer, Florian, et al. “Robust spike antibody responses and increased reactogenicity in seropositive individuals after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine.” medRxiv. Feb 1 2021.

Hall, V., et al. “Do antibody positive healthcare workers have lower SARS-CoV-2 infection rates than antibody negative healthcare workers? Large multi-centre prospective cohort study (the SIREN study), England: June to November 2020.” medRxiv. Jan 15 2021.

Saadat, Saman, et al. “Single Dose Vaccination in Healthcare Workers Previously Infected with SARS-CoV-2.” medRxiv. Feb 1 2021.

Stamataton, Leonidas, et al. “Antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection and boosted by vaccination neutralize an emerging variant and SARS-CoV-1.” medRxiv. Feb 8 2021.

Wherry, E. John. Director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Immunology. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. Apr 19 2021.

“Frequently Asked Questions about COVID-19 Vaccination.” CDC. Last updated Apr 19 2021, accessed Apr 22 2021.

“Benefits of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine.” CDC. Last updated Apr 12 2021, accessed Apr 22 2021.

Pfaeffle, Veronika. Spokesman, FDA. Email sent to FactCheck.org. 19 Apr 2021.

“COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Surveillance.” FDA. Last updated Feb 9 2021, accessed Apr 22 2021.

“Selected Adverse Events Reported after COVID-19 Vaccination.” CDC. Last updated Apr 20 2021, accessed Apr 22 2021.

“Recommendation to Pause Use of Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine.” CDC. Last updated Apr 20 2021, accessed Apr 22 2021.

LaFraniere, Sharon. “U.S. health officials are examining ‘a handful’ of new, unconfirmed reports after J.& J. vaccine pause, the C.D.C. director says.” New York Times. Apr 19 2021.

Kiely, Eugene, and Catalina Jaramillo. “The Facts on the Recommended J&J Vaccine ‘Pause’.” FactCheck.org. Apr 13 2021.

Kelley, Colleen. Associate professor of medicine and epidemiology at Emory University School of Medicine. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. Apr 14 2021.

Seow, Seraphina. “Do Your Vaccine Side Effects Predict How You’d React To COVID-19?” HuffPost. Mar 24 2021, updated Mar 29 2021.

Physician. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. Apr 16 2021.

“Hooman Noorchashm.” Medium. Accessed Apr 21 2021.

Noorchashm, Hooman. “A Letter of Warning To FDA And Pfizer: On The Immunological Danger Of COVID-19 Vaccination In The Naturally Infected.” Medium. Jan 26 2021.

Grady, Denise. “Amy Reed, Doctor Who Fought a Risky Medical Procedure, Dies at 44.” Mar 24 2017.

Hingston, Sandy. “What Are the Chances? A Tale of Love vs. Big Medicine.” Mar 20 2016.

Varga, Steven. Professor of microbiology and immunology, and pathology, at the University of Iowa. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. Apr 19 2021.

Farber, Donna. Professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. Apr 13 2021.

CDC. “The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for Use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine — United States, December 2020.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69(50);1922-1924. Dec 18 2020.

Nordlung, Kristen. Spokesperson, CDC. Email sent to FactCheck.org. Apr 22 2021.

Letizia, Andrew G., et al. “SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity and subsequent infection risk in healthy young adults: a prospective cohort study.” The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Apr 15 2021.

Holm Hansen, Christian, et al. “Assessment of protection against reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 among 4 million PCR-tested individuals in Denmark in 2020: a population-level observational study.” The Lancet. Vol. 397. Issue 10280. Mar 27 2021.

“CDC Real-World Study Confirms Protective Benefits of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines.” Press release. CDC. Mar 29 2021.

Katella, Kathy. “Why Vaccines May Be Helping Some With Long COVID.” Yale Medicine. Apr 12 2021.

Stone, Will. “Mysterious Ailment, Mysterious Relief: Vaccines Help Some COVID Long-Haulers.” NPR. Mar 31 2021.

“Some long-haul COVID patients report vaccines are easing their lingering symptoms.” CBS News. Apr 19 2021.

Wollersheim, Susan. “FDA Review of Efficacy and Safety of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Emergency Use Authorization Request.” FDA presentation. Dec 10 2020.

“Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Emergency Use Authorization Review Memorandum.” FDA.

“Interim Guidance on Duration of Isolation and Precautions for Adults with COVID-19.” CDC. Last updated Feb 13 2021, accessed Apr 21 2021.

“Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Authorized in the United States.” CDC. Last updated Apr 16 2021, accessed Apr 21 2021.

Collins, Francis. “Is One Vaccine Dose Enough After COVID-19 Infection?” NIH. Feb 23 2021.

“France recommends 1-shot vaccine for people who had virus.” Associated Press. Feb 12 2021.