SciCheck Digest

A businessman’s post on Instagram and Facebook wrongly claims that the U.S. government “changed the definition of pandemic” in 2004, suggesting that COVID-19 would not have qualified under the old definition. There’s no evidence for those claims — and COVID-19 is by all means a pandemic.

Full Story

More than a year and a half into the COVID-19 pandemic, the disease has caused a reported 4 million deaths around the world, including more than 600,000 in the United States. But false and misleading claims casting doubt on the seriousness of the disease remain unrelenting.

A businessman with nearly 500,000 followers on Instagram recently took to social media to erroneously claim that the U.S. government previously changed the definition of “pandemic” — and suggest that, under the supposed old definition, COVID-19 would not have been considered a pandemic.

A businessman with nearly 500,000 followers on Instagram recently took to social media to erroneously claim that the U.S. government previously changed the definition of “pandemic” — and suggest that, under the supposed old definition, COVID-19 would not have been considered a pandemic.

But that’s wrong for several reasons.

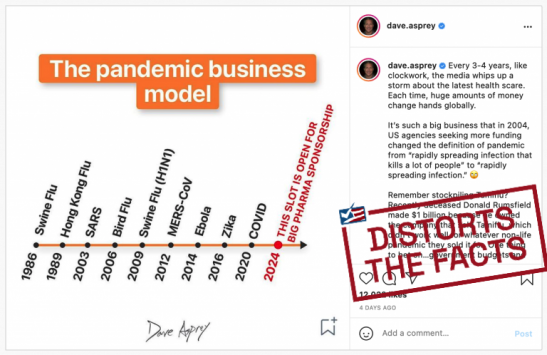

Dave Asprey, who founded the coffee and nutrition company Bulletproof, begins the caption of the post by accusing “the media” of creating a “storm about the latest health scare” every “3-4 years,” arguing that diseases are hyped up for financial reasons, including pharmaceutical company profits.

The image with the post includes a timeline of various disease outbreaks since 1986, and is labeled “The pandemic business model” — even though most of the outbreaks included were not declared pandemics. Of the nine infectious disease events referenced, only two were deemed pandemics: COVID-19 and the 2009 H1N1 “swine flu.”

“It’s such a big business that in 2004, US agencies seeking more funding changed the definition of pandemic from ‘rapidly spreading infection that kills a lot of people’ to ‘rapidly spreading infection,'” the caption of the post continues.

The post, which received more than 12,000 likes and was also repeated on Asprey’s Facebook page, goes on to claim, among other things, that “[y]es, the death rate is higher than normal, but nowhere near what would have made the cut before they changed the definition.”

But there’s no evidence to support the claim that “US agencies seeking more funding changed the definition of pandemic.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes a pandemic as an “epidemic that has spread over several countries or continents, usually affecting a large number of people.” (The same page describes an epidemic as “an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area.”)

Similarly, A Dictionary of Epidemiology, as Vox pointed out last year, defines a pandemic as “an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people.”

COVID-19 — with more than 191 million cases reported to date in countries around the world — no doubt meets that general definition of global spread of a disease.

In 2004, the year referenced by Asprey, Congress did pass the Project BioShield Act. The law — intended to help the U.S. prepare against biological, chemical, radiological, and nuclear threats — allowed the government to guarantee the purchase of countermeasures (such as vaccines) in order to help facilitate their development. It also permitted the Food and Drug Administration to issue emergency use authorizations, or EUAs, for drugs and medical products during public health emergencies; the COVID-19 vaccines being used in the U.S. have been given EUAs.

But the law did not proffer — or revise — a definition for “pandemic.” Nor was any definition laid out in the 2006 Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act.

While there has been some grappling over the years about the precise definition of pandemic — and how severity of a disease should be considered in declaring one — multiple experts told us they had not heard of the U.S. government changing some official definition of the word for the sake of funding, as Asprey alleges.

Frank Snowden, a professor of history and the history of medicine at Yale University, instead noted to us that there was some debate over a change that the World Health Organization made — in 2009, not 2004 — to a webpage offering a definition for “influenza pandemic.”

That page described an influenza pandemic as occurring “when a new influenza virus appears against which the human population has no immunity, resulting in epidemics worldwide with enormous numbers of deaths and illness.”

In early May 2009, not long before the H1N1 pandemic was declared, the WHO revised that page — removing the reference to a pandemic causing “enormous numbers of deaths and illness.” By May 9, 2009, for example, the same page had been changed to say: “A pandemic is a worldwide epidemic of a disease. An influenza pandemic may occur when a new influenza virus appears against which the human population has no immunity.”

That change spoke to the fact that there was not a universally accepted definition of “pandemic,” as a New York Times column documented.

Some criticized the change on the website and argued that H1N1 should not have been labeled a pandemic. But WHO maintained that the change on the website did not affect the H1N1 pandemic declaration, since there were then established phases in place for declaring a pandemic. WHO no longer uses that system.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, co-authored a piece published in October 2009 in the Journal of Infectious Diseases highlighting how there was not a single accepted definition of pandemic.

The authors wrote that there were common traits in previously described pandemics — such as wide geographic extension; disease movement (or “spread via transmission that can be traced from place to place”); and high attack rates and explosiveness (multiple cases occurring in short periods of time).

“There seems to be only 1 invariable common denominator: widespread geographic extension,” they concluded.

In terms of COVID-19, WHO officials were reportedly slow to adopt the word “pandemic.” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in late February 2020 that the decision on whether to declare the disease a pandemic would be based on “an ongoing assessment of the geographical spread of the virus, the severity of disease it causes and the impact it has on the whole of society.”

On March 11, 2020 — citing the rapid increase in cases of COVID-19, its spread across more than 100 countries, and by then thousands dead — Ghebreyesus said WHO “made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic.” Two days later, then-President Donald Trump declared COVID-19 a national emergency.

We sent questions about Asprey’s claims to his company, but we didn’t hear back.

His suggestion that the COVID-19 death rate is “nowhere near what would have made the cut before they changed the definition” is equally dubious. Even the old description of “influenza pandemic” on the WHO website was vague in including the qualification of “enormous numbers of deaths and illness.”

It’s hard to know exactly how lethal COVID-19 is, as we’ve explained. As the WHO has written, studies estimate that the infection fatality ratio, or percentage of deaths out of all infections, is between 0.5% and 1%. But the pandemic is ongoing and not all infections have been diagnosed. The case fatality rate, or percentage of deaths out of confirmed cases, was 1.8% in the U.S., as of July 9.

And as we noted earlier, the disease — because it has spread so widely — has caused more than 4 million deaths worldwide.

“No matter what definition you want to use, COVID-19 is a pandemic,” Rebecca Katz, director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University, told us in an email.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s COVID-19/Vaccination Project is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over our editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation. The goal of the project is to increase exposure to accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines, while decreasing the impact of misinformation.

Sources

“2009 H1N1 Pandemic (H1N1pdm09 virus).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed 15 Jul 2021.

Altman, Lawrence K. “Is This a Pandemic? Define ‘Pandemic.’” New York Times. 8 Jun 2009.

Barnett, Daniel. “Pandemic influenza and its definitional implications.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011.

Bryson Taylor, Derrick. “Is the Coronavirus an Epidemic or a Pandemic? It Depends on Who’s Talking.” New York Times. Updated 11 Mar 2020.

Cohen, Elizabeth. “When a pandemic isn’t a pandemic.” CNN. 4 May 2009.

“COVID-19 Dashboard.” Centers for Systems Science and Engineering, Johns Hopkins University. Accessed 16 Jul 2021.

Doshi, Peter. “The elusive definition of pandemic influenza.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011.

Goldman, Lynn R. Dean, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University. Email to FactCheck.org. 13 Jul 2021.

Gottron, Frank. “The Project BioShield Act: Issues for the 113th Congress.” Congressional Research Service. 18 Jun 2014.

Katz, Rebecca. Director, Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University. Email to FactCheck.org. 14 Jul 2021.

“Lesson 1: Introduction to Epidemiology.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed 18 May 2012.

McNeil Jr., Donald G. “Coronavirus Has Become a Pandemic, W.H.O. Says.” New York Times. 11 Mar 2020.

Morens, David M., et al. “What Is a Pandemic?” Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1 Oct 2009.

Nightingale, Stuart L., et al. “Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to Enable Use of Needed Products in Civilian and Military Emergencies, United States.” Emerging Infectious Diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. July 2007.

“Pandemic preparedness.” World Health Organization. Archived 3 May 2009.

“Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response: A WHO Guidance Document.” World Health Organization. 2009.

“Project BioShield Fact Sheet.” Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. 2011.

“Project Bioshield Overview.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed 19 Jul 2021.

Snowden, Frank. Professor of history and the history of medicine, Yale University. Email to FactCheck.org. 13 Jul 2021.

“WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19.” World Health Organization. 24 Feb 2020.

“WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19.” World Health Organization. 11 Mar 2020.