SciCheck Digest

A rigorous vaccine safety monitoring system has shown that the COVID-19 vaccines are safe and only rarely have serious side effects. But an article shared on social media falsely says that CDC data show more than 18 million people “were injured so badly” by a Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccine “that they had to go to the hospital.”

Full Story

Over 632 million COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered in the United States, under what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls “the most intense safety monitoring program” in the country’s history.

After receiving a vaccine, many people experience mild to moderate symptoms, such as headache, fatigue, fever or pain at the injection site. But these side effects go away in a couple of days and are not considered a safety concern, but rather a sign that the vaccine is working.

Side effects that require medical attention can also occur, but they are the exception.

Yet an article online inaccurately reported that “according to the CDC’s own internal data” more than 18 million people “were injured so badly” from a dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines “that they had to go to the hospital.”

Yet an article online inaccurately reported that “according to the CDC’s own internal data” more than 18 million people “were injured so badly” from a dose of the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines “that they had to go to the hospital.”

“Court Orders CDC to Release Data Showing 18 Million Vaccine Injuries in America,” an Oct. 14 headline from Technocracy News & Trends, which was later shared on social media, misleadingly claimed.

The post refers to data from a CDC safety monitoring system, called v-safe, that the anti-vaccination group Informed Consent Action Network obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. According to the group’s review of the data, out of around 10.1 million v-safe users, more than 780,000, or over 7.7%, “had a health event requiring medical attention, emergency room intervention, and/or hospitalization.” This is “alarming,” it claims, and “should have caused the CDC to immediately shut down its Covid-19 vaccine program.”

A dubious website, Technocracy News & Trends, then went further and misinterpreted the analysis to falsely claim that “about 800,000” people “reported being hospitalized by their COVID vaccination.” The website also rounded the 7.7% figure to 8% and applied it to the vaccinated population of the U.S. to say that “18 million of the 230 million people who received at least one shot may have been hospitalized with an adverse reaction.”

But v-safe collects data on any health event, vaccine-related or not, and the 7.7% — even if taken at face value — was for any kind of medical attention, not just hospitalizations, up to a year after vaccination. It’s inaccurate to say the analysis identified that many hospitalizations after vaccination and misleading to suggest that every event reported was caused by a vaccine. Importantly, a published analysis of v-safe data that shows less than 1% of participants reported receiving medical care in the first week after getting a vaccine.

The CDC said it couldn’t comment on the analysis. But a spokesperson told us in an email that according to the CDC’s data, in the first week after vaccination “reports of seeking any medical care (including telehealth appointments) range from 1-3% (depending on vaccine, age group and dose). V-safe data have shown low rates of medical care after vaccination, particularly hospitalization.”

Over 10 million v-safe users have completed 146 million health surveys, the CDC told us.

“V-safe is not designed to identify causal relationships between vaccines and adverse events,” Dr. Edward Belongia, director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute and an expert in vaccine safety, told us in a phone interview.

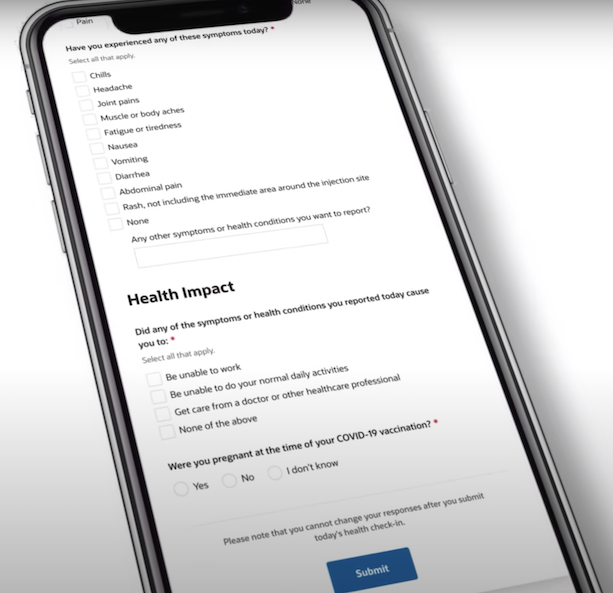

V-safe is a vaccine surveillance program that uses text messages and online surveys to monitor people’s health after getting a COVID-19 vaccine. Every day for a week after each dose of a vaccine, participants who voluntarily opt into the program get messages in which they are asked how they feel that day. They are also asked to report certain symptoms from a pre-populated list, including chills, headache and nausea, or something not listed; and about any health impacts, such as being unable to work, unable to do daily activities, or having to get medical attention. Follow-up texts are sent once a week for the following six weeks and at three, six and 12 months after vaccination. V-safe users are not directed to only report symptoms or health impacts they believe are connected to the shots.

“It does not have the level of detail and granularity needed to accurately assess whether those events are causally related. And you know, there’s no comparison group there, everybody in v-safe is vaccinated. And so it’s impossible to determine whether a vaccine caused a particular adverse event just based on v-safe data,” Belongia told us.

The system is part of a larger early alert reporting system that allows experts to monitor the safety of the vaccines. Belongia, and other experts, say v-safe has limitations. But he says the tool has been helpful to observe common side effects of the vaccines such as pain at the injection site, headache, muscle aches or fever.

“And what we’re seeing is largely consistent with what was seen in the clinical trials: that these symptoms are very common, they’re mild to moderate, they resolved over two to three days, and so there’s really nothing surprising there,” he said.

The data collected through v-safe is not accessible to the public in the way the data from other systems like the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System is. Instead, the information is communicated to the public through multiple studies that analyze v-safe data in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and other journals, and in presentations to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. According to the CDC, v-safe data have been presented in 11 meetings since the rollout of the vaccines — in December 2020; January, March, June, September and October 2021; and in January, April, May, June and September 2022.

Some findings of these studies are that the second dose of the primary series caused more participants to report mild and temporary symptoms or being unable to do normal activity, and that the second booster caused fewer of the expected side effects, such as pain at the site of injection, than the first one. According to the CDC, when the COVID-19 vaccines started to be administered, v-safe was critical in identifying early reports of a severe allergic reaction that occurs rarely after vaccinations.

One study, published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases in March, analyzed v-safe reports between Dec. 14, 2020, and June 14, 2021, after the administration of the Pfizer/BioNTech and the Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. According to its findings, less than 1% of v-safe users reported receiving medical care in the first week after getting a dose of the primary series of either vaccine, and a very small proportion (0.2% or fewer) reported an emergency room visit or hospitalization. Again, even those medical care visits are not necessarily caused by the vaccine and could be coincidental.

ICAN’s Misleading Analysis

Informed Consent Action Network is a Texas-based group founded by Del Bigtree, an anti-vaccination activist. The group has filed several vaccine-related lawsuits against the CDC, the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health. ICAN sued the CDC in December 2021, and again in May 2022, following FOIA requests to obtain all data submitted to v-safe since Jan. 1, 2020. The v-safe program only started after the COVID-19 vaccines were authorized in December 2020.

In August, the CDC agreed to publish on its website the data collected from more than 10 million v-safe participants by Sept. 30. The database would cover reports submitted between Dec. 14, 2020, and July 31, 2022, and would omit any personal identifiers. The agency told Reuters “technical and administrative” issues prevented it from publishing the data on time. Instead, the CDC handed the data directly to ICAN, which published its own analysis on Oct. 3.

On its website, ICAN does not explain the methods used for its analysis. But it mentions the data are limited to the 10 million v-safe users and to the pre-populated fields checked by them, not the information users can add in text boxes. According to the group’s dashboard, the data are drawn from check-ins that occurred up to a year after a vaccine dose. The group also published five downloadable files with raw v-safe data.

FactCheck.org reached out to Aaron Siri and other representatives of Siri & Glimstad, who filed the FOIA litigation for ICAN, but we didn’t hear back from them. We also tried to access the raw data presented, but we couldn’t open the biggest file containing information regarding the health check-ins.

We were able to access one of the files containing symptoms and health impacts, which included 116,294 reports. Out of these reports, 1,046, or 0.9%, were reports of receiving medical care of any kind, and this included multiple reports from the same person over time. Out of those, only seven were for hospitalizations, two of which were for the same person on two consecutive days.

Belongia, the vaccine safety expert, told us the numbers provided by ICAN, including the more than 780,000 users who reported requiring medical care of any kind, are “uninterpetable.”

“We don’t know what the background rate in the population is from v-safe. What would that number have been in a group of people who hadn’t gotten the vaccine?” he said.

Since health problems, including hospitalizations, occur in the population every day, it’s not uncommon for them to happen after vaccination for reasons unrelated to the vaccine. That’s why it’s important to see if a particular event is happening more frequently after vaccination, which could indicate an issue.

The analysis doesn’t mention how long after vaccination a user required medical attention, but included responses up to a year after vaccination, which could explain the difference between ICAN’s numbers and the CDC’s published data. Siri told Reuters that ICAN thought it was important to look beyond one week, since some potential vaccine-related side effects could appear weeks after vaccination. But most side effects occur soon after vaccination, so including longer intervals would include more events that are unrelated to the vaccine.

A user may have gone to a doctor for a completely different reason six months after a vaccine, and, if following v-safe instructions properly, would report it to the system. That user would get a follow-up call from v-safe, for the agency to get more information. But as we said, v-safe doesn’t have the ability to know if any particular event, including a hospitalization, was caused by the vaccine or not.

“And so in order to answer questions like that, in terms of relative risk, you need something like the Vaccine Safety DataLink or VSD, which uses medical records from millions of people around the country, and immunization records to implement scientifically valid studies to determine if there’s an elevated risk after vaccination for particular adverse events,” Belongia said, referring to a network of nine integrated health care organizations, including his, that conducts active vaccine safety surveillance.

“What we’re actually seeing in the data is the exact opposite of what is being suggested by groups like ICAN — these vaccines are very safe. With, you know, a few very rare known exceptions,” Belongia said. “But overall, it’s very clear that the benefits of the vaccines greatly outweigh the risks.”

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s COVID-19/Vaccination Project is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation. The goal of the project is to increase exposure to accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines, while decreasing the impact of misinformation.

Sources

COVID Data Tracker. CDC. Accessed 27 Oct 2022.

Selected Adverse Events Reported after COVID-19 Vaccination. CDC. Updated 24 Oct 2022. Accessed 27 Oct 2022.

V-safe After Vaccination Health Checker. CDC. Updated 18 Jul 2022. Accessed 27 Oct 2022.

Sparber, Sami. “Texas-based anti-vaccine group received federal bailout funds in May as pandemic raged.” The Texas Tribune. 18 Jan 2021.

“BREAKING NEWS: ICAN OBTAINS CDC V-SAFE DATA.” ICAN. 3 Oct 2022.

Rosenblum, Hannah G., et al. “Safety of mRNA vaccines administered during the initial 6 months of the US COVID-19 vaccination programme: an observational study of reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System and v-safe.” Lancet Infectious Diseases. 22 Jun 2022.

Belongia, Edward. Director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 27 Oct 2022

“Share your COVID-19 vaccination experience with v-safe.” CDC. You Tube. 21 Mar 2021.

COVID-19 Vaccine Reporting Systems. CDC. Accessed 27 Oct 2022.

Michelle Gomez, Amanda. “V-Safe: How Everyday People Help the CDC Track Covid Vaccine Safety With Their Phones.” KHN. 7 Sep 2021.

Hause, Anne M., et al. “Safety Monitoring of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Doses Among Children Aged 5–11 Years — United States, May 17–July 31, 2022.” MMWR. 19 Aug 2022.

Hause, Anne M., et al. “Safety Monitoring of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Second Booster Doses Among Adults Aged ≥50 Years — United States, March 29, 2022–July 10, 2022.” MMWR. 29 Jul 2022.

Hause, Anne M., et al. “Safety Monitoring of COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Doses Among Adults — United States, September 22, 2021–February 6, 2022.” MMWR. 18 Feb 2022.

Hause, Anne M., et al. “Reactogenicity of Simultaneous COVID-19 mRNA Booster and Influenza Vaccination in the US.” JAMA Network Open. 18 Feb 2022. 1 Jul 2022.

ACIP Meeting Information. CDC. Accessed 27 Oct 2022.

CDC COVID-19 Response Team; Food and Drug Administration. “Allergic Reactions Including Anaphylaxis After Receipt of the First Dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine — United States, December 14–23, 2020.” MMWR. 15 Jan 2021.

Greene, Jenna. “New data is out on COVID vaccine injury claims. What’s to make of it?” Reuters. 12 Oct 2022.

Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). CDC. Accessed 27 Oct 2022.

Sharan, Martha. CDC Media Relations. Email to FactCheck.org. 25 Oct 2022.