SciCheck Digest

Polio, a paralytic disease caused by a virus, has been eliminated in the U.S. — and nearly wiped out globally — thanks to vaccines. But social media posts are reviving old, false claims that polio is instead caused by pesticides and outbreaks of the disease ended when people stopped using DDT.

Full Story

In the 1940s and 1950s, Americans were terrorized by the threat of polio. Every summer, the highly contagious viral disease caused outbreaks that killed or paralyzed people, most of them children. At polio’s peak in 1952, there were nearly 58,000 cases in the U.S., including more than 3,000 deaths and 21,000 instances of mild or disabling paralysis.

Relief came with the development of polio vaccines: first, with Jonas Salk’s vaccine, made from inactivated, or killed, polioviruses, in 1955, followed by Albert Sabin’s oral vaccine, made from weakened polioviruses, in the early 1960s.

With widespread vaccination, polio cases quickly plummeted. In 1960, 2,525 paralytic cases were reported in the U.S. — a decline of nearly 90% from 1952 — and there were just 61 cases in 1965, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wild poliovirus was eliminated in the U.S. in 1979, meaning there is no ongoing transmission of the virus. Vaccination efforts across the globe have since come close to eradicating the virus. As of last year, wild poliovirus was circulating in just two countries — Pakistan and Afghanistan — according to the World Health Organization.

Despite this well-documented history, posts on social media are circulating false claims that polio is caused by pesticides such as DDT — and that outbreaks subsided not because of vaccination, but because people stopped spraying the chemicals.

“Polio stopped when they stopped dousing the population [with] DDT not some injection,” a popular Instagram post falsely reads.

“Polio wasnt some single strain virus eradicated by a miracle vaxx,” the post’s caption continues. “It was pesticides like Lead Arsenate and its more lethal replacement DDT that lead to lower spine lesions through the gut.”

The Instagram post, which includes three images of DDT being applied on or near people, garnered more than 15,000 likes in its first day. It was subsequently shared on Facebook.

A YouTube video making the same claim — but going further to incorrectly suggest that viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, don’t cause disease and don’t even exist — was also recently shared online.

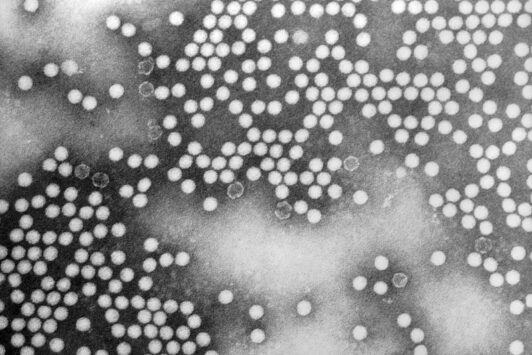

These claims are false. There is no doubt that polio is caused by a virus. This discovery was made in 1908, when scientists injected two monkeys with filtered spinal cord fluid from a boy who had died of polio. The monkeys developed polio and died. Because of the filtration steps, the scientists concluded polio was caused by something smaller than bacteria, likely a virus. Subsequent studies confirmed this. In the 1950s, the virus was observed under an electron microscope.

The polio vaccines themselves are also a testament to the viral nature of polio, since they are made of weakened or killed polioviruses. The scientists who figured out how to isolate and grow poliovirus in a variety of cell types, thereby enabling vaccines, won the 1954 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

There is no evidence that pesticides such as DDT cause polio, or that discontinuing certain pesticides “ended” polio.

For one, polio existed well before DDT. DDT, or dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, wasn’t synthesized until 1874, but polio likely goes back at least several millennia to ancient Egypt.

Nor does the removal of DDT line up with polio’s descent, as our colleagues at Health Feedback noted when addressing similar claims in 2020.

“The peak year for use in the United States was 1959 when nearly 80 million pounds were applied,” the Environmental Protection Agency wrote of DDT in a 1972 press release announcing a ban on agricultural use of the chemical. “From that high point, usage declined steadily to about 13 million pounds in 1971, most of it applied to cotton.”

In 1959, polio had already begun its massive decline with the rollout of Salk’s vaccine. Even ignoring issues of biological plausibility, the timelines don’t match up.

Polio cases, as we said and have explained before, dropped only with the advent of vaccination.

The only connection we could find between DDT and polio is that in the 1940s and 1950s, some U.S. communities sprayed DDT in a misguided effort to avert polio outbreaks, as University of California Berkeley historian Elena Conis has documented.

At the time, it wasn’t known how polio spread — through contact with feces, and to a lesser extent sneezes or coughs — and some suspected flies could be the culprit. DDT had proven to be immensely successful during World War II in fighting insect-borne diseases such as typhus, malaria, dengue and yellow fever. But of course, it would take vaccines to finally quell polio outbreaks.

It’s important to note that while polio is no longer the scourge it once was, the disease remains a risk to Americans who are unvaccinated because cases can be imported. In the U.S., children receive four doses of the inactivated polio vaccine, which are more than 99% effective in preventing severe polio.

Because other countries still use the oral vaccine, which contains weakened but live virus, it’s possible in rare cases for unvaccinated people in the U.S. to develop polio from vaccine-derived strains of poliovirus that originate from people vaccinated abroad and circulate in the community. This appears to be what happened this past summer in an unvaccinated man in New York, as we’ve written.

Fortunately, vaccination protects against polio from wild and vaccine-derived strains, which is why health officials have encouraged anyone who has skipped their polio vaccines to get caught up.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s articles providing accurate health information and correcting health misinformation are made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation.

Sources

“What is Polio?” CDC. Updated 9 Jan 2023.

“History of Polio in Iowa.” The Iowa Heritage Digital Collections, State Library of Iowa. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

Drexler, Madeline. “Infectious diseases & pandemics.” Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health magazine. Fall 2013.

“Polio.” History of Vaccines.org. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

“Vaccine Timeline.” Immunize.org. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

“One Sabin Vaccine For Polio Approved.” Associated Press. 18 Aug 1961.

Estivariz, Concepcion F. et al. “Poliomyelitis.” CDC Pink Book. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

“Polio Elimination in the United States.” CDC. Updated 3 Aug 2022.

“Poliomyelitis.” WHO. 4 Jul 2022.

“Poliomyelitis (polio).” WHO. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

Skern, Tim. “100 years poliovirus: from discovery to eradication. A meeting report.” Archives of Virology. 4 Aug 2010.

Racaniello, Vincent. “100th anniversary of the isolation of poliovirus.” Virology blog. 19 Dec 2008.

“The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1954.” NobelPrize.org. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

“Award ceremony speech, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1954.” NobelPrize.org. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

“Molecule of the Week Archive, Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.” ACS. 13 Dec 2021.

“Polio through history.” Britannica.com. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

“Polio vaccine plays a critical role in eradicating polio; polio is caused by a virus, not by DDT.” Health Feedback. 06 Dec 2020.

“DDT Ban Takes Effect.” EPA. Press release. 31 Dec 1972.

McDonald, Jessica and Jaramillo, Catalina. “Viral Video Makes False and Unsupported Claims About Vaccines.” FactCheck.org. 22 Jan 2021.

Conis, Elena. “A misfire in fighting polio provides clues as to how we’ll beat covid.” Washington Post. 14 Apr 2022.

Conis, Elena. “Polio, DDT, and Disease Risk in the United States after World War II.” Environmental History. 01 Aug 2017.

“Polio Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know.” CDC. Accessed 26 Jan 2023.

Link-Gelles, Ruth et al. “Public Health Response to a Case of Paralytic Poliomyelitis in an Unvaccinated Person and Detection of Poliovirus in Wastewater — New York, June–August 2022.” MMWR. 16 Aug 2022.

McDonald, Jessica. “Poliovirus Found in New York City Wastewater, Not Tap Water.” FactCheck.org. 18 Aug 2022.