Discussing the fallout from the death of Tyre Nichols, Fox News’ Sean Hannity said two academic studies found police officers are as or less likely to shoot Black suspects, showing, “There is no systemic racism in policing. It doesn’t exist.”

But that’s not what the studies say.

Although the second study cited by Hannity did not detect any racial differences when it came to police shootings, it did find racial differences — “sometimes quite large” — in nonlethal uses of force, such as striking a suspect with a baton. The author of the study wrote in the Wall Street Journal in June 2020 that his research “has been wrongly cited as evidence that there is no racism in policing.”

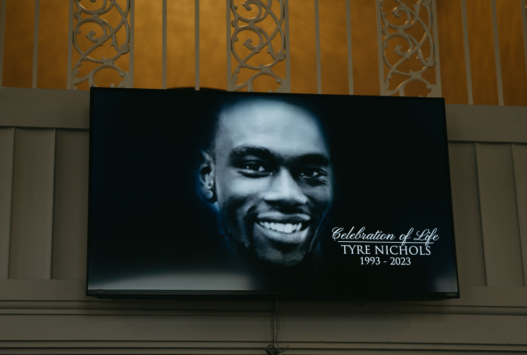

During his program on Jan. 30, Hannity railed against what he said was the media’s false narrative that the Nichols case was based in cultural racism. Nichols, who is Black, was pulled over on Jan. 7 by Memphis police who accused him of driving recklessly. Video shows that Nichols was beaten by officers after he attempted to flee on foot, and he died in the hospital three days later. Five former officers, who are all Black, have been charged with second-degree murder and other charges related to the incident.

“White people do get beaten by the police,” Hannity said. “In fact, far more white people are killed every year by cops than any other race. According to an online organization that tracks this data, 374 white Americans died during police altercations in 2022.”

Hannity appears to be referring to a database compiled by the Washington Post, which found in 2022, 374 white people were shot to death by police, compared with 220 Black and 114 Hispanic people. But the raw numbers can be misleading. Black people make up 13.6% of the American population, yet they represented just over 30% of the people shot to death by police in 2022.

Some have argued that a disproportionate percentage of Black Americans are shot by police because a disproportionate percentage of violent crimes are committed by Black people. In 2016, Wesley Lowery, then a national correspondent for the Washington Post, addressed that issue, citing academic research and the Post’s own analysis, which he said “has consistently concluded that there is no correlation between violent crime and who is killed by police officers.”

Hannity argued that the incidents of white people shot by police are “largely ignored” by the media.

Hannity then continued, “According to a study from Washington State University, listen to this, they were reported on by the Washington Post in 2016. Quote, ‘Officers are three times less likely to shoot unarmed Black suspects than unarmed white suspects.’ And look at this study from the National Bureau of Economic Research covered by the New York Times also in 2016, quote, ‘When it comes to the most lethal form of force, police shootings, the study finds no racial bias.’ So, based on both academic studies and actual data, there is no systemic racism in policing. It doesn’t exist.”

Let’s take a look at the two studies.

Washington State University Simulation Study

The first study, “The Reverse Racism Effect: Are Cops More Hesitant to Shoot Black Than White Suspects?” was published by Criminology and Public Policy on Jan. 14, 2016. The research, led by Lois James, a principal investigator and assistant professor in the College of Nursing at Washington State University, tested 80 patrol officers with the Spokane Police Department on a decision-making simulator to gauge the impact of race on officers’ decisions to shoot a suspect.

The researchers also tested the police officers’ “implicit bias” using Harvard’s Implicit Association test and found that “an overwhelming 96%” demonstrated implicit racial bias, with 78% moderately or strongly associating images of Black people with images of weapons, while no participants associated white people with weapons. In Nichols’ case, all of the police officers charged in his death are Black, but as we have written, research shows there can be implicit bias against members of the same racial group.

In general, the study found that “officers took significantly longer to shoot armed Black suspects than armed White suspects” and that “officers were significantly less likely [three times less likely] to shoot unarmed Black suspects than unarmed White suspects.”

“In other words,” the study stated, “they were more hesitant and more careful in their decisions to shoot Black suspects.”

The authors described the results as a “reverse racism” effect that was “rooted in people’s concerns about the social and legal consequences of shooting a member of a historically oppressed racial group.” (The authors later said in a correction that they had misused the term “reverse racism” in the paper, and should have instead called it, “The Counter Bias Effect.”)

The following January, Criminology and Public Policy published a rejoinder essay attacking the study, titled “Impossibility of a ‘Reverse Racism’ Effect.” In it, the authors argued that the findings are “in contrast to a literature that comprises findings documenting racist practices at every point in the continuum from initially stopping citizens to the use of force.”

In an interview with the Arizona State University School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, James, the lead author of the Washington State University study, noted that “we did find evidence of implicit racial bias, just like previous studies had found.” She said it was “a definite possibility” that her research had been misinterpreted by some, and the “nuanced result” and the study’s “many, many limitations” sometimes got lost in media discussion of the research.

In any case, the study only looked at the responses of a small group of officers in a simulation. It did not attempt to investigate more broadly whether there may be systemic racism in policing, as Hannity claimed.

The NBER Study

The second study cited by Hannity was one authored by Harvard economics professor Roland Fryer for the National Bureau of Economic Research, titled “An Empirical Analysis of Racial Differences in Police Use of Force.” In the study, first released in July 2016, Fryer analyzed data from New York City’s stop-and-frisk program and the city’s Police-Public Contact Survey, as well as summaries of officer-involved shootings in 10 locations around the country and data on police-civilian interactions in Houston.

As Hannity said, the study did conclude: “On the most extreme use of force — officer-involved shootings — we find no racial differences in either the raw data or when contextual factors are taken into account.”

However, it also found, “On non-lethal uses of force, blacks and Hispanics are more than fifty percent more likely to experience some form of force in interactions with police. Adding controls that account for important context and civilian behavior reduces, but cannot fully explain, these disparities.”

In an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal, Fryer wrote that his research “has been widely misrepresented and misused by people on both sides of the ideological aisle.”

“It has been wrongly cited as evidence that there is no racism in policing, that football players have no right to kneel during the national anthem, and that the police should shoot black people more often,” Fryer wrote.

Fryer noted in the op-ed that his research found there are “large racial differences in police use of nonlethal force.”

“My research team analyzed nearly five million police encounters from New York City,” Fryer wrote. “We found that when police reported the incidents, they were 53% more likely to use physical force on a black civilian than a white one. In a separate, nationally representative dataset asking civilians about their experiences with police, we found the use of physical force on blacks to be 350% as likely. This is true of every level of nonlethal force, from officers putting their hands on civilians to striking them with batons. We controlled for every variable available in myriad ways. That reduced the racial disparities by 66%, but blacks were still significantly more likely to endure police force.”

We should note here that Nichols was not shot by police. But video shows he was punched, kicked and struck with a baton.

Fryer noted that his research also found that even when compliant, Black suspects “were 21% more likely to suffer police aggression than compliant whites.”

“People who invoke our work to argue that systemic police racism is a myth conveniently ignore these statistics,” Fryer wrote.

But again, his analysis also found “no racial differences in shootings overall.”

“Our analysis tells us what happens on average,” Fryer wrote. “It isn’t average when a police officer casually kneels on someone’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. Are there racial differences in the most extreme forms of police violence? The Southern boy in me says yes; the economist says we don’t know.”

Seven months after Fryer’s study was released, the American Journal of Public Health published a study by James Buehler, a professor at Drexel University’s School of Public Health, that came at the issue of racial disparities in the use of lethal force by U.S. police from a different angle.

Buehler analyzed five years’ worth of national vital statistics and census data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on deaths resulting from “injuries inflicted by the police or other law-enforcing agents, including military on duty, in the course of arresting or attempting to arrest lawbreakers, suppressing disturbances, maintaining order, and other legal action.”

Buehler described his analysis as a “population-level perspective” alternative to Fryer’s research, and he found that “the mortality rate among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic individuals was 2.8 and 1.7 times higher, respectively, than that among White individuals.” Based on those results, Buehler concluded, “Substantial racial/ethnic disparities in legal intervention deaths remain an ongoing problem in the United States.”

Other Research

Of course, the two studies cited by Hannity are not the only ones on racial disparities in policing.

“There are several studies that have shown that Black Americans are roughly three times as likely as White Americans to be killed by police, and some showing they are more than five times as likely as White Americans to be killed unarmed,” Dylan Jackson, an assistant professor in the Population, Family and Reproductive Health Department at Johns Hopkins University who studies policing, told us via email.

Jackson cited the research from Buehler, as well as the Mapping Police Violence database, which uses media reports about police violence and claims to be the “most comprehensive accounting of people killed by police since 2013.”

While disparity “doesn’t in and of itself mean that structural or systemic racism is the cause,” Jackson said, “recent research has begun to provide some evidence that this is the case.”

For example, a study titled “The Relationship Between Structural Racism and Black-White Disparities in Fatal Police Shootings at the State Level,” published in the Journal of the National Medical Association in 2018, created a “state racism index,” based on residential segregation, and gaps in incarceration rates, educational attainment, economic indicators and employment status. It found: “For every 10-point increase in the state racism index, the Black-White disparity ratio of police shooting rates of people not known to be armed increased by 24%.”

Jackson noted that residential segregation by race also is a factor. Jackson cited a study published in the same journal in 2019 that found, “The level of racial residential segregation was significantly associated with the racial disparity in fatal police shooting rates.” The study’s authors concluded, “Efforts to ameliorate the problem of fatal police violence must move beyond the individual level and consider the interaction between law enforcement officers and the neighborhoods that they police.”

There is academic debate about the root cause of racial disparities in policing, and whether or how much it is due to systemic racism or other factors.

As Fryer wrote about his study, “Racism may explain the findings, but the statistical evidence doesn’t prove it. As economists, we don’t get to label unexplained racial disparities ‘racism.’” But, conversely, the studies certainly don’t conclude that “systemic racism in policing … doesn’t exist,” as Hannity claimed.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.