Q: Is the development of offshore wind energy farms in the U.S. killing whales?

A: Whales have been dying at an unusual rate along the Atlantic Coast since 2016, often from ship strikes or entanglements with fishing gear. Federal agencies and experts say there is no link to offshore wind activities, although they continue to study the potential risks.

FULL QUESTION

I’m fairly skeptical the ocean wind farms can cause whale deaths. What is the truth?

FULL ANSWER

Between December 2022 and March 31, 30 large whales have been stranded and died on or near the shores of the East Coast, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Twenty-seven have been baleen whales, a type of whale that has baleen plates instead of teeth, including 21 humpbacks that have washed ashore between New York and North Carolina.

Scientists suspect a variety of factors are behind the whale deaths, which appear to be a continuation of a years-long period of unusually high mortality for marine animals. Contrary to claims made by critics of wind energy, there is no indication that the strandings have anything to do with seafloor surveys being done in preparation for the installation of wind turbines.

The acoustic sources being used in these surveys are either completely out of the hearing range of baleen whales or only capable of slightly disturbing their behavior, an expert told us. Regulations also require operators to make sure there are no whales nearby when conducting a survey.

“There’s basically zero chance that those surveys have caused any mortality,” Douglas Nowacek, the chair of marine conservation technology at Duke University, told us in a phone interview.

Despite the lack of evidence, conservative media outlets and others have been spreading such claims on social media for months, with some appropriating the phrase “save the whales” to express their opposition to wind farms.

“Wind Surveying Is KILLING our Whales,” Fox News’ Jesse Watters wrote on Facebook on Jan. 12, sharing a segment of his show with the same name.

A day later, during a segment titled, “The Biden Whale Extinction,” Fox’s Tucker Carlson blamed wind farms for “killing a huge number of whales.” He added: “This is the DDT of our times,” referring to the infamous pesticide that has been banned in the U.S. since 1972.

The focus on whales comes as many wind projects are being planned, pumped by efforts to achieve the Biden Administration’s goal to deploy 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030, enough to power 10 million homes.

The projects have faced pushback from local communities and multiple other hurdles. Misinformation campaigns, some from fossil fuel interests, have divided environmentalists and created animosity between some commercial fishermen and those in favor of clean energy.

In March, Fox’s Laura Ingraham continued to push the unfounded narrative. “These whales that are washing up on our beaches is a direct result of the pre-construction that’s taking place here off of New Jersey,” a commercial fisherman claimed during an interview, a clip of which was shared on social media. “The argument is always oil and gas is so bad for the environment,” Ingraham replied, “how ironic that what they’re doing is almost certainly killing large swaths of the whale population.”

But as we’ll explain, there is no reason to think wind development activities are behind the whale losses.

“I don’t think there is a single scientist out there who thinks that these deaths are being caused by wind energy activities,” Andrew Read, a marine science and conservation expert also at Duke University, told the Gothamist this month. “I think the people who are making those claims have other reasons to make those claims.”

Ongoing Whale Deaths

The unusual number of dead whales is not new, nor is there evidence it’s related to the work being done in preparation for the construction of large-scale wind turbine farms, according to three federal agencies and experts.

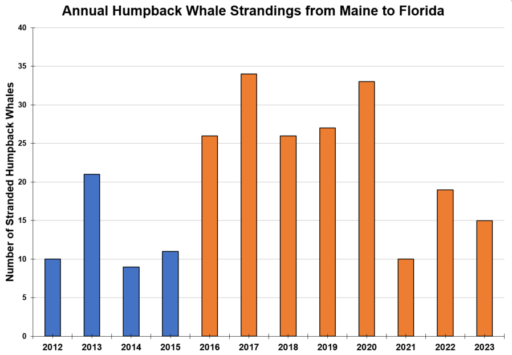

The whale mortality observed this winter, officials say, is part of a larger, unexpected and “significant die-off” of humpbacks, or what’s known as an unusual mortality event, that goes back to 2016. Since then, 190 stranded humpback whales have been registered along the Atlantic Coast from Maine to Florida.

The North Atlantic right whale, which is an endangered species, and the minke whale have also been under unusual mortality events, known as UMEs, both starting in 2017. Three minke whales and two right whales have been found dead this year; both right whales died with signs of entanglement.

Vessel strikes and entanglement with fishing gear are two of the biggest hazards for whales. According to data from NOAA and the Marine Mammal Stranding Center, a nonprofit that rescues and rehabilitates marine mammals in New Jersey, some recently stranded whales showed signs of strikes and entanglements, although those events could have occurred after death. The final necropsy results may be able to clarify the timing.

About 40% of the necropsies performed in humpbacks in the ongoing UME that started in 2016 show evidence of a ship strike or rope entanglement, according to NOAA. The causes for the other 60% have been inconclusive, in part, officials say, because the carcasses decompose quickly, making it difficult to determine a cause of death.

Partial or full necropsies were possible in only half of those humpback cases. Examinations are often not possible because the corpses are inaccessible, have decomposed, or require lots of people and equipment.

Vessel strikes and entanglement are also the leading causes of mortality and serious injuries in the right whale UME.

Several factors, experts and officials have said, could be increasing the risk of these hazards. For one, climate change is warming oceans and changing the distribution of prey that marine species depend on. As a result, whales are altering their migration routes and moving out of protected areas and closer to the shores, where they are more vulnerable to ship strikes and entanglement with fishing gear.

Humpback populations are also growing, so there are more of them everywhere. Shipping activity has also increased, particularly recently. According to the Port Authority, in 2022, the ports of New York and New Jersey moved a “record-high annual cargo total, with 27 percent growth over pre-pandemic 2019.”

“As the humpback whale population has grown, their occurrence in the mid-Atlantic has increased,” a NOAA Fisheries representative explained in a media briefing on Jan. 18. “These whales may be following their prey, which we’re hearing from our partners in the region are reportedly close to shore this winter. More whales in the water and traveled areas by boats of all sizes increases the risk of vessel strikes.”

NOAA has said that to date, no whale death has been attributed to offshore wind activities.

“I have not heard of any injuries or damage caused by offshore wind energy development,” Michael J. Moore, senior scientist and director of the marine mammal center at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, told us in an email.

The Marine Mammal Commission, an independent governmental agency whose mission is to protect marine mammals, confirmed what other agencies have said in a Feb. 21 statement: “Despite several reports in the media, there is no evidence to link these strandings to offshore wind energy development.”

Why Wind Surveys Unlikely To Pose Serious Risks to Whales

Currently, in the U.S., there are two operating offshore wind projects, in Rhode Island and Virginia Beach, and two projects under construction, in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

No construction activities have occurred offshore New Jersey, where many of the whales have washed up. Nor has the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which manages offshore renewable energy developments, approved any construction and operations plans for offshore wind in that state yet, according to an email sent to FactCheck.org by the agency and a statement by the state’s Department of Environmental Protection.

Instead, most of the offshore wind activity taking place on the Atlantic Coast right now, including in New Jersey, is related to data collection. According to BOEM, that includes surveys to understand the geology of the locations where wind turbines may be installed and surveys to identify marine-protected species, shipwrecks, archeological sites and habitats.

To map the seafloor, wind farm developers typically use high-resolution geophysical, or HRG, surveys, which use different kinds of sound systems, or acoustic sources. Some of these could affect whale behavior, but they are not known to lead to deaths.

“I just want to be unambiguous,” Benjamin Laws, deputy chief for the permits and conservation division at NOAA Fisheries, said in the Jan. 18 media briefing. “There is no information that would support any suggestion that any of the equipment that’s being used in support of wind development for these site characterization surveys could directly lead to the death of a whale.”

Much of the surveying uses very high frequency sources, which allow for high-resolution mapping and are used to detect corridors for electricity cables, Nowacek said. The sound gets absorbed quickly by the water, he said, and is “way out of the range of hearing of baleen whales” — and even beyond the hearing of some dolphins and porpoises.

Other HRG sources, such as sparkers and boomers, use lower frequencies that are in the hearing range of whales. But as BOEM bioacoustician Erica Staaterman explained during the media briefing, these sources are very different from the seismic air guns used by the oil and gas industry, which are designed to penetrate deep into the seafloor and are therefore very high-energy and very loud.

The lower frequency sources used for wind farms don’t need to penetrate as deep, since they’re just used to locate an area to build the turbines, Nowacek said. As a result, they use less energy, for shorter periods of time and in smaller areas, using more narrow sound beams.

Nowacek said a whale “would have to be literally right underneath” to be impacted. And that’s very unlikely, since operators must abide by a series of stringent mitigation protocols set by NOAA, as we will explain later. And even then, the impact wouldn’t be lethal, he said.

“They may move, they may be displaced, they may, you know, change their swimming patterns, they may change their vocal behavior,” he said of the whales. “But it’s not going to kill them.”

“BOEM and NOAA Fisheries rigorously assessed the potential effects of HRG surveys associated with offshore wind development in the Atlantic, and the agencies concluded that these types of surveys are not likely to injure whales or other endangered species,” BOEM told us in an email.

Laws also noted that the acoustic systems used for surveying are “commonly used around the world,” and “there are no historical stranding events that have been associated with use of systems like these.”

Also arguing against any connection between the surveys and the whale deaths is the fact that these surveys have been occurring for decades. Federal, state and academic institutions began doing offshore wind energy-related surveys before 2010, BOEM told us in an email. Surveys by developers started in 2011 in Delaware and in 2015 in New Jersey. And before any offshore wind development, similar surveys took place for scientific research.

Risks and Mitigation

As we said, there is no evidence whale and other marine mammal mortality has been caused by offshore wind development. However, experts and officials acknowledge these projects have potential risks to whales, including those associated with increased noise, vessel traffic and entanglement, and are working to mitigate them.

“The exploration, construction, and operation” of offshore wind energy “is not risk neutral for marine mammals,” Moore, Woods Hole’s marine mammal center director, told us in an email.

Whales and other species are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act. To do acoustic surveys or to do any other activity other than fishing that could potentially disturb or harm marine mammals, wind operators and others need to get what is called an incidental take authorization.

Projects that have the potential for serious injuries or deaths of marine mammals, such as some military exercises and oil and gas activities, require a Letter of Authorization. None of those have been issued for wind energy.

“NOAA Fisheries has not authorized (or proposed to authorize) mortality or serious injury of whales for any wind-related action,” the agency told us in an email.

Instead, the concern with wind farms is what the Marine Mammal Protection Act calls harassment, which is defined on two levels: Level A, which means the activities have the potential to produce a non-serious injury to marine mammals; and level B, which means the work has the potential to produce a behavioral disturbance.

Currently, there are several active incidental take authorizations for offshore wind, but only two include both level A and B harassment. Laws said during the briefing that for the site characterizations surveys, only behavioral disturbance, or level B harassment, has been authorized.

A series of other protective measures are in place to minimize the risks of offshore wind activities, such as slow zones for vessels to avoid collisions (less than 10 knots, or 11.5 miles per hour) and exclusion areas, places where surveys are not allowed to occur for certain periods of time.

Operators must also have at least one independent protected species observer on duty at all times during the day, and at least two at night, to detect protected species and avoid any contact.

Surveys can’t be conducted if an endangered marine mammal, such as a right whale, is closer than 1,640 feet from the vessel, or if any other marine mammal is closer than 328 feet. If a whale is found to be approaching what is known as the “shutdown zone,” the surveying must stop until the animal moves out of the area.

Mitigations for level A harassment, which is anticipated with pile driving activities when turbines are installed, are more stringent. Each project has its own set of mitigations, but these include sound attenuating systems, seasonal restrictions when pile driving is not allowed, and larger clearance zones (3,280 feet for right whales and 1,640 feet for other baleen whales).

A less understood potential issue posed by offshore wind development is the potential impact of the turbine towers on the dynamics and ecology of surface waters, which are rich in food sources for fish and whales.

According to a study published in 2022, offshore wind infrastructure in the deeper ocean could disturb the seasonal cycles of ocean stratification, which could impact zooplankton, the tiny animals that are a crucial food source for baleen whales. The study says this could have both negative and positive effects, and that more studies are needed to identify them and mitigate or maximize them accordingly.

Some of those issues are addressed in a draft strategy proposed by NOAA and BOEM “to protect and promote the recovery of North Atlantic right whales while responsibly developing offshore wind energy,” NOAA told us in an email.

“One of the biggest challenges for whale conservation is to keep protection measures current,” Moore said.

Because of climate change, he said, it is becoming more difficult to predict where whales will be at a certain time of the year, since their food sources are moving due to changes in the seawater temperature. As a result, whales end up in places with no protections.

“Obviously, we need to mitigate and reverse climate disruption,” he wrote. And offshore wind energy is one of the solutions. “Thus, we need to develop offshore wind while minimizing the impact on marine mammals.”