While the risks associated with COVID-19 generally have decreased over time due to prior exposure to the vaccines and the virus, some people remain at elevated risk, such as the elderly and immunocompromised. The updated COVID-19 vaccines and, in some cases, a new monoclonal antibody can provide increased protection for this group.

“At this point, many people have had multiple vaccines and we are seeing a lot less severe and life-threatening illness, especially in people who have had recent vaccination,” Dr. Camille Kotton, clinical director of Transplant and Immunocompromised Host Infectious Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital, told us. “Nonetheless, we are still seeing significant severe disease, hospitalization, even life-threatening disease, especially in people over the age of 65 or who are immunocompromised.”

We spoke with Kotton, who is also a member of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, about the current state of affairs for people at elevated risk of severe disease from COVID-19 and the tools they can use to protect themselves.

For some people who are immunocompromised, a newly authorized monoclonal antibody, Pemgarda, or pemivibart, may provide an additional layer of protection, Kotton said. These antibodies may substitute for a person’s own antibodies and help block the coronavirus from entering a person’s cells.

Even so, Kotton emphasized the importance of getting this year’s updated COVID-19 vaccines. “The majority of immunocompromised patients have not had a first dose of the 2023/2024 vaccine,” she said. They, along with people age 65 and up, are eligible for multiple doses of the updated vaccines this year.

Who Remains at Increased Risk from COVID-19?

Last month, the CDC updated guidelines for people with COVID-19, removing the previous standard five days of isolation and replacing it with symptoms-based guidance. The move was part of a transition away from the emergency response phase of the pandemic to recovery and maintenance phases, the agency explained.

Rates of COVID-19-associated hospitalization have declined across adult age groups since early pandemic waves. There is also evidence that outcomes have improved for those who are immunocompromised. However, these groups remain at elevated risk from COVID-19, Kotton said.

As of the latest census, just around 17% of the U.S. population was age 65 or over. But between October 2023 and January 2024, around two-thirds of COVID-19 hospitalizations were among those 65 and older, according to data from the CDC. Older Americans make up an increasing proportion of those hospitalized for COVID-19, as outcomes have improved more markedly for younger people.

People who are immunocompromised also are hospitalized for COVID-19 and die from the disease at a relatively high rate. Between October 2022 and November 2023, 16% of all adult COVID-19 hospitalizations were among people with immunocompromising conditions, and 28% of in-hospital deaths occurred in this group.

People can be immunocompromised for a variety of reasons, and to varying degrees. Sometimes, a health condition itself alters a person’s immune system’s ability to respond to infection. These conditions can include certain blood cancers, advanced or untreated HIV, or primary immunodeficiency, a group of rare genetic diseases in which some portion of a person’s immune system is altered and doesn’t work properly.

At other times, the treatment for a disease weakens someone’s immune system. For instance, people are considered immunocompromised if they are receiving immunosuppressive treatments associated with transplant or various treatments for conditions such as autoimmune disease or cancer.

Recent estimates indicate around 7% of U.S. adults report having immunosuppression, up from around 3% in 2013.

The growing availability of advanced therapies for various diseases has likely contributed to the increasing percentage of immunocompromised Americans, Kotton said. Previously, for “many of those people, we did not have such successful treatments,” she said. “Unfortunately, now one of the side effects of all of those treatments can be a higher risk of infection.”

How Can People Protect Themselves from COVID-19?

The Food and Drug Administration approved, and the CDC recommended, updated COVID-19 vaccines in September. (For more information, see “Q&A on the Updated COVID-19 Vaccines.”) Since then, the updated vaccines have been shown in multiple studies to reduce the risks of hospitalization and other negative outcomes — including among the elderly and immunocompromised.

As is recommended for everyone 6 months and up, people who are elderly or immunocompromised should get an updated 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine if they haven’t yet, Kotton said. People who are immunocompromised or elderly are also eligible for additional vaccine doses. Protection from the vaccines wanes as time passes, particularly among these groups, she said.

People age 65 and up should get a second dose of the updated vaccines at least four months after their previous dose, according to the CDC. People who are moderately or severely immunocompromised “may get additional updated COVID-19 vaccine doses” if it has been at least two months since their last COVID-19 vaccine, the agency says.

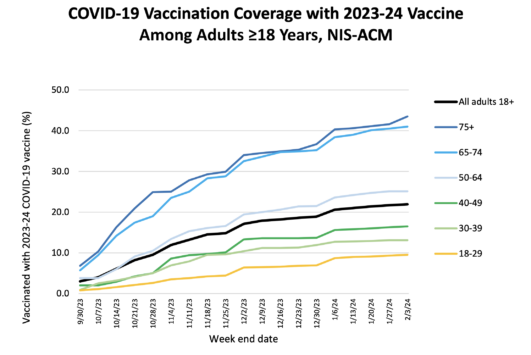

Despite these recommendations, just over 20% of American adults had gotten the updated vaccines as of February. Uptake was a bit better among adults 65 and older, with more than 40% having gotten the shots.

In a recent study of electronic health records through February, just 18% of immunocompromised people had gotten an updated shot. The same study showed that the vaccines reduced the risk of hospitalization in this group by 38% between seven and 59 days after getting the shot and 34% in the 60 days following that, compared with immunocompromised people who hadn’t received an updated vaccine.

“I actually believe that we should focus many of our efforts on really encouraging uptake of the 2023/2024 COVID-19 vaccine, and that everybody has a first dose and at least two or more months later get a second dose so that they remain well vaccinated,” Kotton said, referring to the population of people who are immunocompromised.

What Is Pemgarda and Who Might Benefit?

On March 22, a new potential tool for mitigating COVID-19 risk was authorized by the FDA. Pemgarda, the monoclonal antibody, received an emergency use authorization for people who are moderately to severely immunocompromised and who are unlikely to have a sufficient immune response to COVID-19 vaccination. It became available for purchase by wholesalers on April 4.

It is the first preventive antibody treatment to be authorized since a prior monoclonal antibody combination, called Evusheld, was taken off the market in January 2023, based on data indicating that it was unlikely to help protect against the latest viral variants that were circulating.

Pemgarda is given to people who do not have COVID-19 or a known exposure. It consists of an antibody shown to recognize a section of the spike protein, which is part of the virus that causes COVID-19. The product was authorized based on calculations indicating that receiving it should lead to sufficient antibodies in a person’s blood to protect against JN.1, the current dominant variant in the U.S.

Pemgarda may benefit a subset of immunocompromised people, Kotton said, but it is not a substitute for vaccination. People who are vaccinated “tend to develop multiple forms of immunity that seem more protective than just administration of a monoclonal antibody alone,” she said.

Vaccination should lead to both the production of antibodies and a cellular immune response, she explained. A drug like Pemgarda may help people who are not producing sufficient antibodies on their own in response to vaccination.

It is not cut and dried how well someone who is immunocompromised will respond to vaccination, however. “When we give immunocompromised people vaccines, some respond by developing an antibody, others develop a cellular immune response, and it’s not always predictable that if they develop one that they will develop the other,” Kotton said. “And so it’s been challenging to know who is actually well protected.”

It is clear that the people who are at risk of severe COVID-19 include those with recent bone marrow transplant, people with certain cancers such as multiple myeloma, or those taking certain drugs given for various cancers and autoimmune diseases. “We do think that those populations could potentially benefit” from Pemgarda, Kotton said.

These patients are not only at risk of severe disease, Kotton said, but of chronic infections. Distinct from long COVID, these long-term infections occur when a person is unable to clear an active infection.

“Otherwise, it seems that it’s not clear that there will be widespread benefit to all immunocompromised populations, in the era of widespread, numerous vaccination doses,” Kotton said.

What Are the Obstacles to Getting Pemgarda?

Kotton emphasized the importance of practical considerations, such as cost and logistics, when considering COVID-19 prevention measures.

Evusheld, the previously available preventive treatment, was provided for free by the U.S. government, she said. The same is not true for Pemgarda. Its maker, Invivyd, announced a wholesale acquisition cost of nearly $6,000 per dose. This is the list price a manufacturer charges wholesalers, although it may not represent the price they actually pay after discounts. Costs to patients will vary depending on insurance coverage.

Preventive monoclonal antibodies are available without cost-sharing for people covered by Medicare, who make up a portion of those eligible for Pemgarda, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. However, the amount individuals with private insurance pay will depend on their insurance plans and whether the monoclonal antibody is covered.

While Evusheld was given as two injections, Pemgarda is an infused drug, Kotton added, increasing the logistical challenges for both patients and health care providers. Patients must sit for an hour-long infusion, followed by a two-hour observation period, for a drug that may be given every three months. “Already Evusheld was a very challenging rollout,” Kotton said. “We did not have staff or capacity.”

In contrast, the private sector cost of the COVID-19 vaccines for those 12 and older is between $115 and $130 per dose. And people in the U.S., including those without insurance, should be able to get COVID-19 vaccines for free.

As Pemgarda is rolled out, Kotton said, it will be important to push for equity in who receives it. “I think it’s important to think hard about how we would make the monoclonal antibody available to all severely immunocompromised people who would really benefit and not just people that might be able to pay for it,” she said.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s articles providing accurate health information and correcting health misinformation are made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation.