Para leer en español, vea esta traducción de El Tiempo Latino.

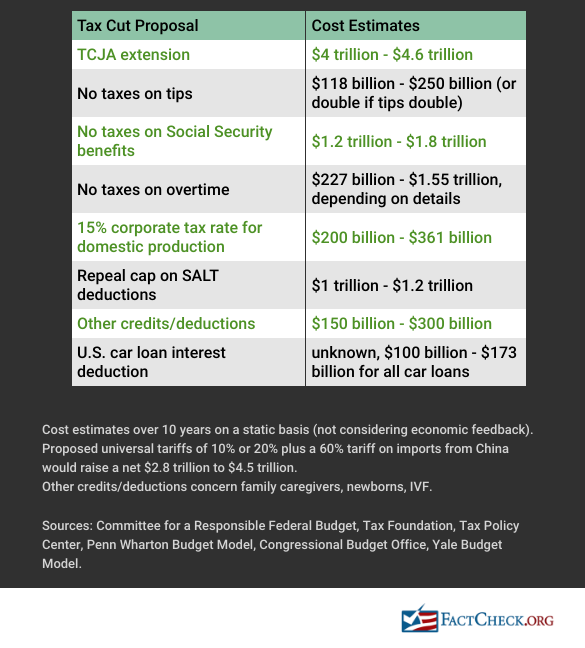

In addition to extending the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, one of his signature achievements in his first term, President-elect Donald Trump has proposed a long list of tax cuts, from eliminating taxes on Social Security benefits to lowering the corporate tax rate. Altogether, they could cost upwards of $8 trillion to $10 trillion over a decade.

The high-end estimate of $10 trillion is double the amount of all federal COVID-19 relief spending.

But implementing tax changes requires Congress to act. The TCJA’s individual income tax provisions are set to expire at the end of 2025, making an extension of those measures a legislative priority next year.

“The expiring individual provisions of the TCJA will be extended sometime in 2025,” Howard Gleckman, a senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, wrote in a Nov. 6 post predicting what would happen with Trump’s wish list on taxes. As for a “lengthy list of highly targeted tax cuts” — including a corporate tax cut to 20% or 15%; the elimination of taxes on tips, overtime and Social Security benefits; and providing tax credits for car purchases and family caregiving — “[i]t remains to be seen which of these he’ll really pursue,” Gleckman wrote.

Trump also has proposed new or higher tariffs on goods imported from other countries, and he could impose at least some tariffs without congressional action. Those would bring in government revenue, but act as a tax increase on Americans, as the cost of tariffs are typically passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices, as we’ve reported. Tax experts include the impact of higher tariffs when analyzing Trump’s tax plans.

In the days leading up to the election, Trump repeatedly cited his call for no taxes on tips, overtime and Social Security. Often, he added that he supported “a tax credit for family caregivers who take care of their parent or loved one.” In North Carolina on Nov. 2, he called for expanding the child tax credit.

“My plan will massively cut taxes for workers and small businesses,” he said the day before the election in Pennsylvania, echoing a line in many of his speeches.

We’ll look at Trump’s tax proposals, their cost and what impact they could have on taxpayers.

TCJA

Details and cost: Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act into law on Dec. 22, 2017. It wasn’t the largest tax cut in history, as Trump has repeatedly claimed, but it was sizable: a $1.5 trillion price tag over 10 years at the time. For individual income taxes, the law changed the marginal tax rates and associated income thresholds, increased the standard deduction and eliminated the personal exemption, increased the child tax credit, limited deductions for state and local taxes as well as mortgages and home equity lines of credit, and increased the threshold for estate taxes, among other measures.

But to get the bill to Trump’s desk, Republicans in Congress used reconciliation, a process that allows the Senate to pass a bill with a simple majority, rather than the 60 votes normally needed to break a filibuster and move legislation forward. With reconciliation, the tax plan had to meet a set target for spending and revenue, and it couldn’t add to the deficit after 10 years.

In order to meet that budget requirement, Republicans wrote the law so that most of the individual tax cuts expire at the end of 2025 (including all of the provisions mentioned above). That’s why Congress needs to act again in order to extend the cuts. Now, extending sunsetting provisions in the law would add about $4 trillion to the deficit over 10 years, according to estimates from the Penn Wharton Budget Model, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the Tax Foundation and the Congressional Budget Office. The CBO projected the cost at $4.6 trillion including interest payments.

When including economic effects of the tax cuts, PWBM estimated the cost at $3.83 trillion, while the Tax Foundation put it at $3.5 trillion.

Trump also has called for allowing the TCJA’s cap on deducting state and local taxes to expire. Not extending that limit on the so-called SALT deduction would add another $1 trillion to $1.2 trillion to deficits over a decade, according to the Tax Foundation and CRFB.

Republicans will hold 53 seats in the Senate in 2025, so they may need to use reconciliation again to pass a tax bill. The Tax Policy Center’s Gleckman wrote in a Dec. 4 post that “if lawmakers are not able to agree on deep, longer-term spending cuts or tax increases, GOP lawmakers may be forced to extend all the individual provisions of the TCJA only temporarily, instead of making those 2017 tax cuts permanent.”

Gleckman noted that Sen. Mike Crapo, the chair of the Senate Finance Committee come January, has said that extending the 2017 provisions wouldn’t need to be paid for under Senate rules, because it would be a continuation of current policy. “It would hardly be the first time Congress treats a tax cut extension as costing nothing, but it violates the spirit, if not the letter, of congressional budget rules,” Gleckman wrote. “Besides, whatever gimmick Congress may invent to make it look like extending the TCJA is costless, Treasury still will have to borrow at least $4 trillion more over 10 years than if it does not extend the TCJA.”

Other Republican senators have voiced support for Crapo’s “current policy” method, which would bypass the need for reconciliation. At a Dec. 18 GOP press conference, Sen. Rick Scott called it a “logical way” of avoiding “massive tax increases,” and Sen. Ron Johnson called it “common sense.” But Scott also embraced spending cuts, saying that lawmakers “expect significant reductions in the cost of government. We don’t have a choice. … We have got to get to a balanced budget now.”

There’s also the possibility of Congress increasing tariffs, as Trump has proposed, to pay for the TCJA extension though reconciliation. “But Trump doesn’t appear to want to wait for congressional action,” Gleckman wrote. “And if he imposes the tariffs unilaterally, using them as an offset may not be so easy since congressional scorekeepers normally don’t count administrative actions in their budget estimates.”

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a budget watchdog group, has an online tool that shows how Congress could pay for at least some of the TCJA extension by modifying the tax law’s provisions. “Putting the federal budget on a sustainable path already requires tough choices against current law, choices that would become much more challenging with an extension of the TCJA because it would worsen the fiscal outlook significantly,” CRFB said in a Dec. 3 post. “Delaying action will result in taxpayers bearing the consequences of interest on a growing government debt load and slower economic growth.”

CRFB also has noted that while some politicians will claim that tax cuts pay for themselves by spurring economic growth, “analyses from across the political spectrum have found that the economic effects of extending the expiring parts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) would offset 1 to 14 percent of the revenue loss – falling well short of the 100 percent needed to pay for itself.”

Impact on taxpayers: The Tax Policy Center estimated that about 75% of households get a tax cut with a TCJA extension, and 10% pay more in taxes. Nearly half of the benefits — 45% — are reaped by households earning $450,000 and above in 2027.

That year, on average, middle-income earners would get a tax cut of about $1,000, or about 1.3% of after-tax income because of the extension, compared with the current law, under which the cuts expire at the end of 2025. In other words, taxpayers may not experience this as a new tax cut, but rather a continuation of the current tax structure. Those earning $1 million or more (the top 1%) would get an average tax cut of about $70,000, or 3.2%. Those earning $5 million and above (the top 0.1%) save about $280,000 in taxes, or 3%.

According to the Tax Foundation’s estimates of making the TCJA permanent, the bottom quintile of earners would get an average 2.2% boost in after-tax income, while the middle quintile gets 1.9% and the top quintile gets 3.4% in 2026. The top 1% would get a 4.8% boost.

Tips

Details and cost: At a June 9 rally in Nevada, home to many service industry workers, Trump proposed eliminating federal taxes on tips.

Under current law, tips are taxed just as hourly or salaried wages are: Workers must pay income tax on their tips; in addition, both employers and workers pay payroll taxes, which fund Social Security and Medicare. Trump hasn’t released details on his no-taxes-on-tips policy, but in another Nevada rally, on Aug. 23, he suggested he wanted to eliminate both income and payroll taxes on tips, saying workers would be able to keep 100% of their tip income. (That would mirror a House Republican bill introduced in June.)

The cost of eliminating all taxes on tips would be about $150 billion to $250 billion over 10 years, according to CRFB’s estimate, and significantly more if workers and employers shifted more income to tips. “The magnitude of that behavioral effect is uncertain and would depend significantly on the regulatory guardrails that accompany the policy,” CRFB said in June. “As an illustrative example, if tips were increased by 10 percent, the policy would reduce revenue by $165 to $275 billion, and if they doubled it would increase deficits by $300 to $500 billion.” (If the TCJA provisions are extended, the base price of the tips proposal drops by 10% to 15%.)

While some politicians are in favor of this idea — including Vice President Kamala Harris, who also proposed it, limited to income taxes up to a certain threshold — economists and tax experts have roundly criticized it as inequitable for low-wage workers who don’t earn tips, potentially harmful to tipped workers and an incentive for other workers — from lawyers to plumbers — to adopt tipping.

Impact on taxpayers: About 4 million people were tipped workers in 2023, according to an analysis by the Budget Lab at Yale. That’s about 2.5% of all workers, and 5% of workers in the bottom quarter of earners, which are those earning less than $18 an hour.

A good portion of those tipped workers already don’t pay federal income taxes because they earn so little: about 37% in 2022 were below the federal tax threshold, the Budget Lab estimated.

For tipped workers who do pay federal income taxes, the impact would vary, depending on total income and the percentage of income coming from tips. But a hypothetical example from the Tax Foundation shows that the savings could be substantial, particularly when compared with those who earn the same amount of money but only in the form of wages.

Senior policy analyst Alex Muresianu at the Tax Foundation wrote in a July post: “Consider two individuals: a cashier named Tracy and a waitress named Susan. Tracy and Susan each earn $34,000 in income. Tracy receives all of her income in wages, while Susan receives $19,000 in wage income and $15,000 in tips. Under the status quo, they each take the standard deduction and end up paying around $2,100 in taxes.”

But if Susan didn’t pay taxes on her tips, she would owe $440, a savings of more than $1,600.

Muresianu wrote that “if the goal is to deliver tax relief to lower- and middle-income taxpayers, raising the standard deduction (which effectively serves as a 0 percent federal income tax bracket) would achieve that regardless of occupation.”

Eliminating payroll taxes on tips would also reduce tipped workers’ future Social Security benefits, which are calculated based on average earnings.

Dean Baker, senior economist at the Center for Economic & Policy Research, also explained in a thread on X that some tipped workers with children could see lower earned income tax credits if they have lower taxable income, which could leave some workers worse off — despite not paying income taxes on tips. The tax credit is a fixed percentage of income, so the amount increases as income rises for eligible low- and moderate-income working families. (See this chart from the Tax Policy Center for more information.)

Social Security

Details and cost: Trump wants to eliminate taxes on Social Security benefits for seniors, a proposal he announced in late July and repeated many times on the campaign trail.

About 40% of Social Security beneficiaries pay federal income taxes on up to 50% or up to 85% of their benefits, depending on their income. “This usually happens if you have other substantial income in addition to your benefits,” the Social Security Administration explains. “Substantial income includes wages, earnings from self-employment, interest, dividends, and other taxable income that must be reported on your tax return.”

In order to owe taxes on benefits, an individual would need to make $25,000 (or $32,000 for joint filers) in what’s called “combined income.” Combined income is adjusted gross income, nontaxable interest and half of Social Security benefits.

The tax revenue goes to the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. According to a September report by the Congressional Research Service, $50.7 billion of that tax revenue in 2023 went to the Social Security trust funds, making up 3.8% of the funds’ income, while $35 billion went to the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund, an amount that was 8.4% of the funds’ income.

The Penn Wharton Budget Model estimated that ending taxes on benefits would cost $1.2 trillion over 10 years. The cost would be lower if the TCJA is extended, due to lower tax rates compared with current law. The CRFB put the cost higher, at $1.6 trillion to $1.8 trillion over 10 years.

Impact on taxpayers: Those earning $32,000 or less wouldn’t benefit from the tax cut, according to a Tax Policy Center analysis of the impact in 2025. Those earning between $33,000 and $63,000 would get an average tax cut of $90. Middle-income earners, making between about $63,000 and $113,000, would get a $630 tax cut on average, while those earning $113,000 to $205,800 would get a cut of $1,190 on average.

The top 0.1% of taxpayers, earning $4.7 million and up, would get a tax cut of $2,470 on average.

Note that the analysis couldn’t break out only seniors, so it includes Social Security disability and survivor benefits.

Seniors could get fewer Social Security benefits in the future under this tax proposal. Without another source of income to replace the lost tax revenues, the Social Security and Medicare trust funds would become insolvent sooner: more than one year sooner, in 2032, for Social Security, and six years sooner, in 2030, for Medicare, according to CRFB’s estimates.

At the point of insolvency, spending on benefits would be limited to the revenue each year, and benefits would be cut by 25%, compared with 21% under current law. “After-tax benefits would not meaningfully change – though reductions would be larger for lower income seniors and smaller for higher income seniors,” CRFB said.

An October report from CRFB estimated that Trump’s larger agenda, including eliminating taxes on tips, Social Security and overtime, restricting immigration, and increasing tariffs, would speed up Social Security’s trust fund insolvency by three years.

Overtime

Details and cost: In Arizona on Sept. 12, Trump added another tax cut proposal: ending “all taxes on overtime.”

“That gives people more of an incentive to work. It gives the companies a lot — it’s a lot easier to get the people,” he said.

It would encourage people to work more overtime, but it would also “significantly distort labor market decisions,” according to the Tax Foundation. “Employees would be encouraged to take more overtime work, and hourly or salaried non-exempt jobs may become more attractive if the benefit is not extended to salaried employees who are exempt from Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) overtime rules,” Tax Foundation researchers wrote in a Sept. 13 report.

Federal law requires that employers pay certain employees 1.5 times the hourly rate for time worked beyond 40 hours a week.

As employees get more overtime work, employer’s costs increase. “For some employers, the increased attractiveness of overtime work may fit well with their existing operations. For other employers, they may need to be more aggressive to contain overtime requests as total labor costs rise,” the Tax Foundation said.

It estimated the cost of exempting all overtime pay from income taxes at $680.4 billion over 10 years. But if taxes were only eliminated for the 50% bonus paid for overtime, the cost would be $227 billion. If all income taxes plus employees’ payroll taxes were nixed, that would cost $1.1 trillion over a decade, with the cost rising to $1.55 trillion if employers’ payroll taxes also go away.

CRFB looked at several scenarios and found that “no taxes on overtime would reduce revenue by $250 billion to $1.4 trillion on a static basis and by $1 to $5 trillion in the extreme case that all workers eligible for the tax cut switched to hourly.” That’s also over 10 years.

Impact on taxpayers: About 8% of hourly workers and 4% of workers earning salaries regularly work overtime that qualifies for boosted pay under the Fair Labor Standards Act, the Budget Lab at Yale estimated. Occasionally, another 4% of hourly workers and 1% of salaried workers clock in overtime. That means working more than 40 hours a week and getting paid 1.5 times the regular pay for the extra hours.

Most salaried workers and some hourly workers aren’t eligible for such overtime pay under the FLSA. Employees in “executive, administrative, professional and outside sales” jobs, as well as certain computer jobs, are exempt from overtime if they are paid a salary that amounts to at least $684 per week, the Department of Labor explains. Teachers are also exempt. The Budget Lab estimated 70% of salary workers and 7% of hourly workers are ineligible or exempt.

The impact of this kind of tax cut on overtime-eligible workers would depend, of course, on the details of the tax cut, how much overtime someone worked and the pay rate. The Budget Lab provided a couple of scenarios. In one, a medical records technician earning $23 an hour and working 50 hours a week wouldn’t pay taxes on more than $17,700, while a retail store supervisor working the same hours and earning the same at an annual rate wouldn’t qualify for overtime or the tax cut.

“Tax proposals that favor one form of income over others create opportunities for tax avoidance,” the Budget Lab wrote in the September analysis, explaining that employers and employees in overtime exempt jobs could find ways to change their compensation to either save on labor costs or taxes.

Tariffs

Details and revenue: On the campaign trail, Trump proposed a broad 10% or 20% tariff on all imports and a 60% tariff on imports from China.

As we explained in an article on Trump’s tariff proposals from the campaign, several economic analyses say raising tariffs would bring in federal revenue and would increase costs for Americans, acting like a tax.

U.S. importers pay tariffs to U.S. Customs and Border Protection in the form of customs duties at ports of entry. Importers mostly pass on the cost of the tariffs to consumers in the form of higher prices for the goods, economists say.

Trump’s proposal for a universal 10% tariff and 60% tariff on Chinese goods would raise federal revenue by a net $2.8 trillion over 10 years, according to a Tax Policy Center analysis. Increasing the baseline tariff to 20% would bring in a net $4.5 trillion over 10 years.

The Tax Foundation estimated that a 20% universal tariff plus a 50% tariff on Chinese goods would raise $3.8 trillion over a decade.

In its analysis, the Tax Foundation said that using tariffs to pay for tax cuts “comes with major downsides,” calling tariffs “a particularly distortive way to raise revenue” because they can spark retaliation from other countries.

After the election, on Nov. 25, Trump proposed more tariffs, saying in a social media post that he would put a 25% tariff on imports from Mexico and Canada “until such time as Drugs, in particular Fentanyl, and all Illegal Aliens stop this Invasion of our Country.”

Impact on taxpayers: The Tax Policy Center found that a 10% universal tariff plus 60% on Chinese goods would reduce after-tax income in 2025 by about $1,800 per household on average. Upping the universal tariff to 20% would lower average after-tax income by about $3,000.

For the 10%/60% scenario, TPC said: “All income groups would see similar percentage declines in after-tax income as a result of Trump’s tariffs, ranging from 1.7 percent to 1.9 percent. … The biggest exception: Those with the highest incomes, whose after-tax incomes would fall by about 1.4 percent.”

Similarly, the Peterson Institute for International Economics estimated, conservatively it says, that the 20%/60% scenario would increase a typical middle-income household’s costs by more than $2,600 a year.

Erica York, a senior economist and research director at the Tax Foundation, told the fact-checking website Verify in September that the 20%/60% proposal could raise costs by more than $6,000 on average for all households.

Other Tax Proposals

And Trump has mentioned several other tax changes.

He has proposed lowering the corporate tax rate to 15% for companies that make their products in the U.S. (The rate for all companies is 21% under the TCJA.) That would reduce federal revenues by $200 billion or $361 billion over 10 years, according to CRFB and the Tax Foundation, respectively.

In Michigan in October, Trump called for a tax deduction for interest on car loans, later specifying this would be “only for cars made in America.”

For taxpayers with qualifying car loans, the bottom 90% of income earners would save an average $200 to $300 on their taxes, if taxpayers wouldn’t have to itemize deductions in order to get the tax benefit (only 10% of taxpayers itemize), according to the Budget Lab at Yale’s analysis. “But the savings would be largest for those at the top, since deductions create larger savings for those with higher tax rates and the income tax is progressive,” the Budget Lab said. “The average benefit for those in the top 1% would be closer to $1,500.”

Trump said he would repeal clean energy tax incentives signed into law by Biden, which include credits for electric vehicles, solar and wind energy, as well as home energy improvements, a move that would raise $921 billion over 10 years, the Tax Foundation said. The TPC, which didn’t include the EV incentives in its analysis, said this would “modestly increase taxes at all income levels.”

He called for ending “double taxation” of some Americans living abroad, who must file U.S. tax returns. Alan Cole, a senior economist at the Tax Foundation, wrote in October that only a few million Americans would be affected. “For most, the burden is not the payment of tax: it is the filing of tax. Most Americans abroad likely owe nothing, or relatively little,” he said. Cole explained that even those with low incomes are required to file their taxes, which can be complex, but there’s a large exemption for income earned abroad: $120,000 in 2023.

Trump also has floated a tax credit for family caregivers, a deduction for newborns and mandated coverage for in vitro fertilization treatment, which altogether could cost about $150 billion to $300 billion over 10 years, depending on the details, CRFB said.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.