Este artículo estará disponible en español en El Tiempo Latino.

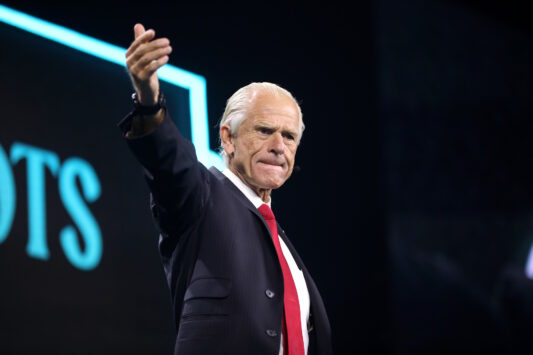

Before President Donald Trump paused some new tariffs that he unveiled on April 2, several economic groups estimated that tariffs he has announced this year could raise between roughly $2 trillion and more than $4 trillion in federal revenue over a 10-year period. But that’s well short of the $6 trillion or $7 trillion that White House trade adviser Peter Navarro claimed the tariffs would raise to help pay for tax cuts, including an extension of the 2017 tax law.

On April 6, during an interview on “Sunday Morning Futures,” Navarro talked about the revenue-generating potential of Trump’s tariffs on imports. Trump announced on April 9 that he was suspending some of his so-called “reciprocal” tariffs for 90 days. (We’ve written about how the tariffs aren’t really reciprocal.)

“These tariff revenues, by the way, Jackie, $600, $700 billion they are going to raise a year, $6 to $7 trillion over the 10-year period,” Navarro told Jackie DeAngelis, who hosted the Fox News show that day. “They’re going to help pay for the tax cuts. I’ll tell you this, Jackie. Every single dollar that comes in, in tariff revenues that we take from the foreigners who have been cheating us, are going to go right to the American public in terms of tax cuts and debt reduction.”

Navarro is wrong to suggest that the tariffs would be paid by “foreigners,” though foreign businesses could decide to “lower their prices to absorb some of the tariffs,” as the Tax Foundation explains. He also ignored the fact that tariffs, also known as customs duties, are a tax increase on the U.S. importers who pay the tariffs – not foreign countries. And because those importers often pass at least some of those costs on to U.S. consumers through price hikes, tariffs are considered to be regressive taxes that affect lower-income households more than others as a percentage of income.

“If you raise $600 billion more a year in revenue for the federal government, you are taking that amount away from individuals and businesses in the private economy,” the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board wrote in a late March piece.

Multiple economic analyses project that Trump’s tariffs will reduce the after-tax income of households by potentially thousands of dollars a year, on average.

Independent analyses also show that Navarro may be exaggerating the amount of money that the government may collect from the tariffs.

We asked the White House to explain Navarro’s revenue projection, but we did not receive a reply. We also inquired if Navarro’s estimate was the basis for the president’s April 8 claim that his tariffs are bringing in “$2 billion a day” to the U.S., which would add up to more than $7 trillion over 10 years, but the White House didn’t tell us that, either. (So far, U.S. Customs and Border Protection has said that it has collected about $200 million per day in “additional associated revenue” from 13 of the president’s tariff-related executive actions this year.)

Howard Gleckman, a senior fellow for the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, guessed that Navarro’s claim was based on “some simple math.” In an April 8 blog post, he said that the senior trade official may have taken the $3.3 trillion in U.S. imports of goods in 2024 and multiplied it by a tariff rate of 20%, “a rough estimate of all the Trump tariffs,” producing a revenue total of over $600 billion annually, or more than $6 trillion over 10 years.

“Simple. But wrong,” wrote Gleckman. He said that “Trump’s tariffs are likely to fall far short of Navarro’s prediction,” making it highly doubtful that there would be enough revenue to cover the cost of parts of Trump’s economic agenda, specifically an extension of Trump’s 2017 tax cuts, as well as other tax-cutting proposals, such as the elimination of taxes on tips, overtime pay and Social Security benefits.

Indefinitely extending tax cuts for individuals in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act alone would cost $4 trillion over 10 years, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

In fact, the Tax Policy Center has estimated that all tariffs Trump announced through April 2, including a tariff of at least 10% on all U.S. imports of foreign goods and higher tariff rates on specific countries, would raise about $3.5 trillion – $189.5 billion in 2025 and then $3.3 trillion from 2026 to 2035. That estimate, Gleckman said, doesn’t include the economic impact of any retaliatory tariffs on U.S. goods, which some countries have already announced, nor does it account for an anticipated decline in corporate profits and wages because U.S. firms have to pay the tariffs.

“If it did, tariff revenues would be even lower,” Gleckman noted.

And the TPC isn’t the only organization with tariff revenue estimates lower than Navarro’s.

- In an analysis updated on April 9, the Tax Foundation estimated that Trump’s 2025 tariffs, altogether, “will raise $2.2 trillion in revenue over the next decade on a conventional basis ($1.6 trillion on a dynamic basis) and reduce US GDP by 0.8 percent, all before foreign retaliation.” Projected revenue is lower on a dynamic basis, the Tax Foundation said, because that estimate reflects “the negative effect tariffs have on US economic output, reducing incomes and resulting tax revenues.”

- Meanwhile, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget has said on April 7 that all of Trump’s announced tariffs, if made permanent, could raise $3 trillion from 2025 to 2034. Because the tariffs could reduce real gross domestic product by 0.6%, CRFB said its revenue estimate would decline to $2.7 trillion once those macro-dynamic economic effects are factored in.

- Likewise, the Budget Lab at Yale University said on April 2, “All tariffs to date in 2025,” if they remain in place, “raise $3.1 trillion [from 2026 to 2035], including the effect of retaliation to date.” That estimate falls to about $2.5 trillion when factoring in “$582 billion in negative dynamic revenue effects,” the Budget Lab said.

- And the Penn Wharton Budget Model, based on all tariffs announced prior to Trump’s April 9 pause, said it “estimates that the Combined Trump Tariffs will generate $4.6 trillion in revenue over 10 years, using recent time-varying demand elasticity estimates.” That’s based on imports declining by 29%. On the other hand, “If baseline import demand in the United States across all goods and services further stagnates over the next decade due to lower economic growth, total new tariff revenue will decrease to $4.13 trillion.” Those estimates include “partially dynamic” economic effects, Kent Smetters, a University of Pennsylvania economics and public policy professor, and the university’s PWBM faculty director, told us in an interview.

None of those analyses predicts as much as $6 trillion to $7 trillion in federal revenue, as Navarro claimed.

We don’t know exactly what tariffs will be put into place by the Trump administration after the 90-day pause on the April 2 tariffs. For now, goods imported from China will face a 125% tariff, and there’s a universal 10% tariff on all imported goods from other countries.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.