Bernie Sanders claims that “Democrats win when the voter turnout is high” and “Republicans win when the voter turnout is low.” But past voter turnout numbers and research on what could happen with higher turnout don’t support such a definitive statement.

Sanders recently made the claim on CBS’ “Face the Nation,” while making the argument that his campaign, not Hillary Clinton’s, could generate the turnout needed for a Democrat to win the presidential election (at the 6:40 mark).

Sanders, May 29: We have the energy and the enthusiasm in our campaign that Clinton’s campaign, frankly, in my view, does not have, that can generate a large voter turnout in November. Democrats win when the voter turnout is high. We can generate that.

Republicans win when the voter turnout is low. Frankly, I don’t know that Secretary Clinton’s campaign can create a high voter turnout.

This is a talking point for Sanders, who also made the claim in February, during one of the debates, and tweeted it.

But as we wrote after that debate, the data on voter turnout in presidential elections don’t show a clear trend. Now, we’ve taken a closer look at the research about what could happen with higher turnout, or even full turnout, and that too doesn’t show that more voters would always lead to Democratic wins.

Let’s start with the data on past presidential elections.

In February, we looked at voter turnout for the voting age population, numbers available from the American Presidency Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara. But one of the directors of that site, John T. Woolley, a political science professor at UC Santa Barbara, told us data on the voting eligible population (which would exclude those not able to vote, such as felons in many states and noncitizens) would be better for this topic.

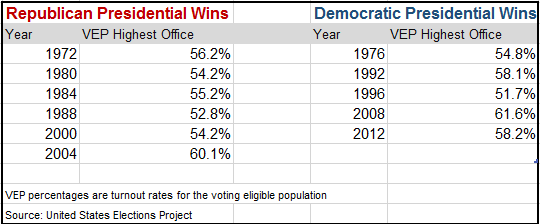

The voting eligible population turnout rates don’t show a clear pattern either in past presidential elections. Here are the lists of Democratic and Republican presidential wins and the voting eligible turnout rates back to 1972. (The data go back to 1789 on the United States Elections Project website, run by Michael P. McDonald, a political science professor at the University of Florida.)

Since 1972 the highest turnout was 61.6 percent in 2008, when Democrat Barack Obama won. The lowest turnout, however, was also for a Democratic president, Bill Clinton’s reelection in 1996. And the second-highest turnout was 60.1 percent in 2004, when President George W. Bush won reelection. The average turnout for Republican winners during this time was 55.45 percent, and the average for Democratic winners was 56.88 percent, a slight edge for the Democrats.

Experts told us the overall voter turnout rate by itself wasn’t that meaningful. Which party benefits from higher turnout depends on who and where the additional voters show up at the polls.

“Most often, higher turnout favors Democrats,” McDonald told us in an email. “Generally, it is true that low propensity voters tend to prefer Democratic candidates. However, this is just a tendency: there are also people who prefer Republicans among these low propensity voters. Thus, depending on who shows up to vote, it is possible to have higher turnout and for Republican candidates to do better.”

Woolley said that “[g]ross turnout is not as important as turnout in ‘battleground’ states.” With an electoral college, drumming up higher turnout in a state that reliably votes Democratic, or Republican, anyway, wouldn’t make a difference. “[M]obilizing the base in California or, say, Kansas will affect aggregate turnout but have no particular consequences for the overall election result.”

Even in battleground states, higher turnout can favor one party over the other, depending on who exactly turns out to vote and how they choose to vote in that particular election. For instance, in Ohio, in 2008, Democrat Obama won the state with 66.9 percent of the voting eligible population voting for the highest office. That’s the highest turnout in the presidential elections in the state since at least 2000 (as far back as the state data go on McDonald’s Elections Project site). But, Republican Bush’s win in 2004 nearly matched that high turnout, with 66.8 percent of the voting eligible population in Ohio casting votes for president. That’s a mere snapshot of two elections in one state, but it shows that Sanders’ claim of a Democratic win with high turnout is far from a given.

Here’s another example: In the presidential elections from 2000 through 2012, the lowest statewide turnout rate for the highest office for eligible voters in Florida was 55.9 percent in 2000, when Republican Bush won in what was a very close and contested vote. But in 2004, Florida’s turnout rate jumped to 64.4 percent, and Bush still won. Obama won the state in 2008 with an even higher 66.1 percent, but again won in 2012 with a lower 62.8 percent.

The Sanders camp has pointed to surveys from the Pew Research Center that show that nonvoters tend to have more liberal views on some policy issues than voters (but not so much on social issues). Pew has also found that nonvoters have weaker partisan ties, but are still more likely to identify as Democrats than Republicans. In terms of demographics, the Pew research finds: “Nonvoters are younger, less educated and less affluent than are likely voters.”

But that doesn’t mean that if all of those nonvoters — or even more of them — voted, Democrats would necessarily win.

The Research and Conventional Wisdom

In 2003, three researchers from the University of California, Berkeley wrote in the American Journal of Political Science that it was “conventional wisdom among journalists and politicians” that “higher turnout would benefit Democrats.” The thinking goes that “since nonvoters in America are drawn disproportionately from the poor, the working class, and ethnic minorities — groups that tend to support Democrats — higher turnout would produce more Democratic votes.” But, they said, “Much empirical research, however, suggests that increased turnout would not necessarily benefit the Democrats.”

One complicating factor is that nonvoters tend to have weaker party loyalty than voters, and, therefore, stronger inclinations to favor a candidate from a party other than the one with which they traditionally identify. That 2003 paper noted that back in 1980 James DeNardo, at the time an assistant professor of politics at Princeton University, had found that higher turnout would “tend to benefit” the political party that is in the minority in that “particular jurisdiction.”

The Berkeley researchers — Jack Citrin, Eric Schickler and John Sides — calculated what the impact would have been on U.S. Senate races between 1994 and 1998 if there had been full voter turnout — that’s if everyone voted — using Census Bureau and exit poll data. They found that “in the majority of cases, nonvoters tend to be more Democratic, sometimes substantially so.” But nonvoters’ partisan leanings “fluctuate significantly across states and over time, and there are instances in which nonvoters are actually more Republican than voters.”

Would full turnout have changed who won these Senate races? In tight races, yes, the increased turnout could have flipped the result. But the researchers found few of those — many races simply aren’t that close — and it wasn’t always the Democrat who came out the winner under these simulations.

They did find that with full turnout “Democrats typically do better,” but the margins are small. “The Democratic candidate’s percent of the vote increases by an average of 1.5 percentage points in 1994, 1.3 points in 1996, and .15 points in 1998,” they wrote. That’s why the close races could have a different outcome if everyone voted, but full turnout wouldn’t make a difference if the election wasn’t tight. Among the four Senate races between 1994 and 1998 for which the researchers found a change in outcome, three benefited the Democrat and one benefited the Republican.

More recently, in 2008, Citrin, Schickler and Sides modeled what full turnout would have meant for the 1992 through 2004 presidential elections in a paper titled “If Everyone Had Voted, Would Bubba and Dubya Have Won?” published in the journal Presidential Studies Quarterly. The bottom line: Again, full turnout could have tipped the balance in very close elections, but wouldn’t have made a difference in others.

“Our estimates suggest that there is a reasonably high probability that Al Gore and John Kerry would have won under universal turnout, but both elections still would have been extremely close,” they wrote. “This suggests that although universal turnout might well tip very close elections in the Democrats’ favor, the electoral landscape would not be transformed. And, of course, the impact of higher but less than universal turnout would depend on which voters were mobilized in a particular contest.”

That paper described the nonvoters as “slightly more Democratic than voters,” explaining that the difference in partisan leanings of voters versus nonvoters in some states was large, but in others, not so much.

More recently, in a March 2015 piece for the Washington Post, John Sides, now an associate political science professor at George Washington University, gave a rundown of the available literature on this topic. President Obama had suggested mandatory voting would make a difference, saying, “That would counteract [campaign] money more than anything. If everybody voted, then it would completely change the political map in this country.” But Sides said, “If everyone voted, a lot would be the same.”

Sides also noted that the differences between voters’ and nonvoters’ political leanings were typically small, and larger differences, such as those found in the 2012 Pew survey — the one cited by the Sanders camp — “are the exception, not the rule.” In a subsequent piece for the Washington Post, Sides explained that calculations by Anthony Fowler at the University of Chicago, as well as Sides and his Berkeley colleagues, suggest that this gap between voters’ and nonvoters’ party identification “may be larger in 2010 and 2012 than in at least some earlier elections,” though that gap may vary from state to state.

McDonald, of the Elections Project site, cited a growing “age gap” in the political preferences of the youth and the elderly in a 2011 piece for Huffington Post, with the youth being more liberal. A much smaller percentage of the youth vote in midterm elections than vote in presidential elections, McDonald wrote, so if they did turnout for the midterms in the same numbers, that could make a difference for Democrats. But only in razor-thin races: McDonald found Democratic candidates would have garnered an additional 1 percentage point of the vote in the 2010 midterms if the electorate had been like that of the 2008 presidential election.

Sides and his colleagues aren’t the only researchers to have reached the conclusion that full turnout would alter very few election outcomes. For instance, Sides cites the work of Thomas L. Brunell of the University of Texas at Dallas and John Dinardo of the University of Michigan. Their November 2004 paper on the simulated outcome of full turnout in the 1952 through 2000 presidential elections concluded: “Higher turnout in the form of compulsory voting would not radically change the partisan distribution of the vote.”

Brunell and Dinardo, whose paper was published in the journal Political Analysis, found that of the 13 elections analyzed, full turnout would produce “no change in the eventual outcome of the election with two possible exceptions: 1980 and 2000.”

The researchers found a “generally small” bias against Democrats in the range of 2 to 3 percentage points, “which is usually insufficient to overturn a presidential election, in large part because most presidential elections are won by more than a percentage point or two.”

A couple of caveats: Higher turnout is different from full turnout. As we noted above, with higher turnout, which party would benefit would depend on which voters cast ballots — that is, where the higher turnout comes from. And as Sides notes in his Washington Post piece, compulsory voting could lead to changes in the behavior of candidates and parties, unknown factors that these universal vote simulations can’t model.

Overall, Sanders’ blanket statement isn’t supported by data or research on past presidential elections. Higher turnout could potentially tip an election to the Democratic candidate, but, the research shows, that would be the case in very close elections. And it depends on where and how the increased turnout votes.

https://www.sharethefacts.co/share/05758abc-43c2-4474-8d5a-89ce3160ec3c