On the campaign trail, former Vice President Joe Biden and President Donald Trump have both claimed that a cure to cancer would soon become a reality — if they were elected in 2020. Experts, however, don’t share that degree of optimism.

Despite considerable progress, especially in recent years, cancer isn’t one disease to cure, and advances in all the many types of cancer are likely to take multiple decades.

Biden was the first to make the outsized promise. In a speech in Iowa on June 11, he briefly alluded to his son’s death to brain cancer in 2015, and then offered his pledge.

“I promise you if I’m elected president, you’re going to see the single most important thing that changes America,” he said. “We’re gonna cure cancer.”

A week later, on June 18, Trump made a similarly prophetic statement during his 2020 kickoff rally in Orlando, Florida, as he listed several agenda items for a second term.

A week later, on June 18, Trump made a similarly prophetic statement during his 2020 kickoff rally in Orlando, Florida, as he listed several agenda items for a second term.

“We will come up with the cures to many, many problems, to many, many diseases, including cancer and others,” he said. “And we’re getting closer all the time.”

It’s difficult to fact-check promises — after all, we can’t predict the future. And while both politicians suggested these cures would come while they were still in office, neither explicitly said when exactly this would happen. But oncologists say curing cancer is unlikely to happen within the next decade.

Still, experts do expect to be able to cure more patients in the coming years, and some types of cancer are already curable today.

We’ll run through some important considerations when thinking about cancer and its cures, give an overview of some recent successes, and spotlight some challenges that remain.

Cancer Isn’t One Disease

The first problem with both politicians’ statements, several experts told us, is that cancer isn’t a single disease.

“Cancer is not just one entity. It’s not just tuberculosis or HIV/AIDS,” said Timothy Chan, a physician-scientist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. “It’s really a catch-all name for hundreds and maybe even thousands of types of diseases.”

What unites all cancers is the theme of uncontrolled cell growth. As we’ve explained before, cancer happens when DNA mutations allow a cell to replicate with abandon, forming a tumor that eventually can metastasize, or spread throughout the body.

In most cases, many mutations are needed to form a tumor; these can be inherited or come about during cell division or through environmental exposures.

The specific reasons for the unchecked growth, however, vary, both between and even within cancer types, which are usually categorized by the cell or tissue type of the originating tumor.

Kevin Kelly, an oncologist and clinical researcher at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University, said that when he started in medicine 25 years ago, lung cancer was only considered to have two types. “Now, they can actually subtype into 10 or 12 different types of lung cancer, based on the genomic profile,” he said. “That’s what makes it so complicated.”

And, as Chan said, no two people’s cancers are the same. Even within a single tumor, there can be genetic differences among cells as they collect new mutations, some of which can mean the difference between a portion of a tumor being treatable or not.

All of this means that curing cancer is unlikely to be a singular achievement. “There are going to be a thousand different cures,” said David Weiner, a cancer researcher and executive vice president of the Wistar Institute.

Given that “curing cancer” would mean finding many cures, Chan said doing so would be “impossible” in the next 10 years. “Maybe the next 50 years to cover everything,” he said.

Other experts were similarly skeptical about such an ambitious time frame.

“It’s going to take over a decade for us to see real impact on cancers,” said Kelly.

There Are Already Cures

Even if all cancers can’t be cured soon, multiple experts were quick to point out that some cancers can already be cured, no advances needed.

“We cure cancer every day,” said David Porter, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, in an email.

In his specialty of blood cancer, he said, many leukemia and lymphoma patients can be cured with conventional chemotherapy or with bone marrow or stem cell transplants.

Many pediatric cancers, too, are considered curable, Kelly said, as are many cases of testicular cancer, which is treated with chemo, surgery and sometimes radiation.

As long as a cancer hasn’t spread very far, surgical removal of a variety of tumors, including of the breast, prostate, lung and colon, can also prove curative, Kelly added.

Still, he acknowledged, for cancers that have already metastasized, most are not currently curable.

It’s worth noting that in oncology, the word “cure” operates a bit differently than in most other medical specialties. As the National Cancer Institute explains, a cure means a person’s cancer has disappeared and will never come back.

While that happens for some people, doctors cannot guarantee a person who has been successfully treated won’t ever see their cancer return. Cancer is wily, and if even one leftover cancer cell escapes a treatment, it could come roaring back.

As a result, many physicians refer to remission instead, with complete remission referring to no symptoms or signs of cancer. The longer this remission lasts, the more likely it will continue. If there is no recurrence after five years, the chance of the cancer returning is low enough that some doctors will use the word “cure.”

Recent Successes & Realistic Expectations

Even if Biden’s and Trump’s pronouncements seem overly optimistic, researchers are nevertheless encouraged about many newly developed treatments and those in the pipeline.

“Treatments for cancer are being developed at an incredibly rapid pace. They are becoming more selective and targeted, and more potent,” said Porter, adding that he fully expects to be able to cure more patients with more types of cancer in the near future.

Some of the hottest new additions to the cancer arsenal are immunotherapies that take advantage of the body’s immune system to attack cancer.

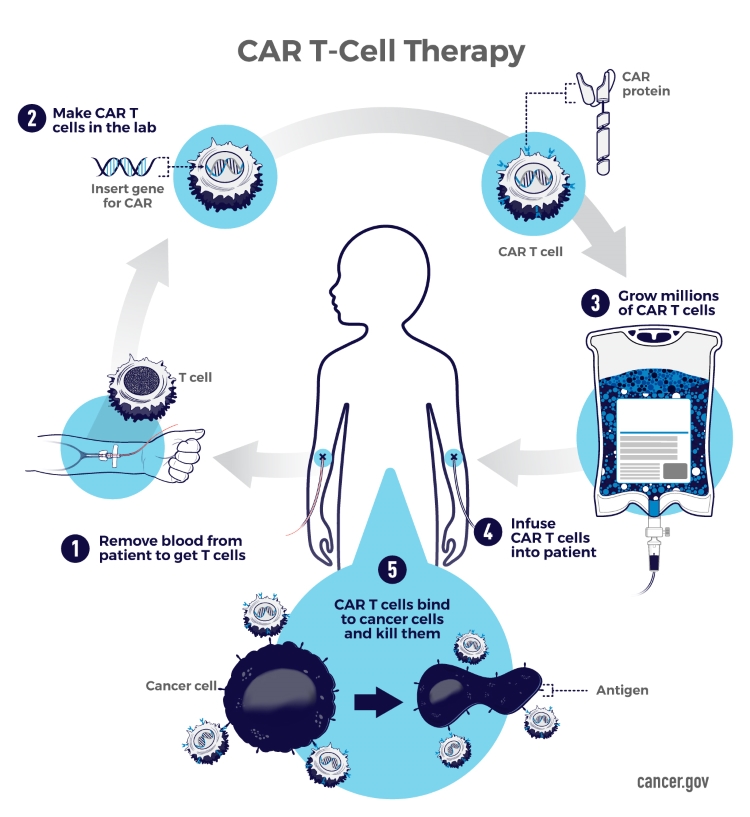

One form of immunotherapy that Porter has helped develop is CAR T-cell therapy, which involves removing white blood cells known as T cells from patients, reengineering the cells in the lab to recognize a person’s cancer, and then infusing the cells back into the patient.

While the treatment can trigger a sometimes life-threatening reaction as the immune system kicks into gear and eliminates its targets, physicians have learned more about how to reduce those side effects, and a subset of patients go into remission.

“It may be too early to know if CAR T-cells are curing patients permanently,” Porter said, “though I believe we have enough follow-up to suggest that many of these patients are likely cured.”

Currently, the Food and Drug Administration has approved two such treatments for blood cancers, one for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia up to the age of 25, and another for adults with certain aggressive B-cell lymphomas.

Both approvals have been within the last two years, and are reserved for patients whose cancers have not responded to other treatments. Within the next year, Porter expects the FDA to review new CAR T-cell therapies for other blood cancers, including multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Another set of game-changing immunotherapies are checkpoint inhibitors, one of which successfully treated former President Jimmy Carter’s advanced melanoma.

Because cancer cells aren’t quite normal, T cells can often recognize them and take them out — but usually, only with some help. By blocking special molecules on the surface of cells that tumors use to stay hidden, these drugs spark T cells into action, turning them into cancer-killing machines.

Checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for a variety of tumors, including skin, lung, kidney, bladder, and head and neck cancers.

But not all treatments cure, and not all patients benefit — and herein lies the main problem. By one estimate, only about 12% of patients respond to checkpoint inhibitors, and even when patients do, tumors can become resistant to the drugs.

This is in part why Chan suggests a more plausible goal for the next decade is a “big improvement” in cancer treatment, perhaps being able to significantly extend the survival of patients in over half of the cancers. “That doesn’t sound as sexy” as a cure, he said, “but it’s more realistic.”

The challenge now is figuring out how to make these therapies and others work for more patients. One idea researchers are pursuing is mixing and matching different drugs and other therapies together, including with cancer vaccines, to find successful combinations.

In the end, though, Chan remains wholly optimistic. “I view cancer as a very complicated process, but a very dissectable and understandable process,” he said. “It’s a matter of just really figuring it out.”

What It’ll Take

Regardless of who wins the White House in 2020, experts told us the way to speed up progress on cancer is to bankroll more research. Without funding, breakthroughs can’t happen.

More specifically, experts said they want to see more high-risk, high-reward work being funded. These projects are the kind that are more likely to fail, but they’re also more likely to lead to a genuinely new idea that could be revolutionary for the field.

“You want to try new things and be novel,” said Wistar’s Weiner. “Investment in high-risk, high-reward research is absolutely critical.”

Jefferson’s Kelly also suggested making it easier for researchers to share large sets of data and for more patients to seek out clinical trials.

“Only around 8% of patients actually get into a clinical trial,” he said. “And if we could double or triple it, we could increase how quickly we can test new drugs.”

Both candidates, to varying degrees, have proposed elements of these ideas in the past. But if budget proposals are expressions of a president’s priorities, Trump hasn’t yet made cancer a prime concern.

In fiscal year 2020, the Trump administration proposed shrinking the National Cancer Institute’s overall budget by almost $900 million, or 15%. NCI is the cancer wing of the National Institutes of Health, and is the primary federal agency doing cancer research and training.

Trump also suggested cuts to the NCI in both of his previous budgets, but Congress balked and provided funding increases. Since fiscal year 2003, the NCI budget has generally increased by a small amount every year, but those additions have not kept pace with inflation.

Trump has, however, supported childhood cancer research. In his 2019 State of the Union speech, he highlighted an initiative and promised that sector an extra $50 million each year for the next 10 years — the equivalent of a 10% annual boost. According to Science magazine, the initiative includes a large push for increased data sharing.

For his part, Biden was put in charge of former President Obama’s Cancer Moonshot project in 2016, and was instrumental in passing the 21st Century Cures Act, which funded the effort with $1.8 billion over seven years.

In 2017, Biden and his wife started a nonprofit, the Biden Cancer Initiative, to encourage collaboration in the fight against cancer. When Biden announced his 2020 run in April, both he and his wife stepped down from their roles in the organization. This month, the group suspended its operations.

Biden has not formally addressed how he would approach NCI funding if elected president, but said in an appearance at the AARP/Des Moines Register Presidential Forum on July 15 in Iowa that he would double NIH funding and create an ARPA-H, a health version of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

FactCheck.org Rating:

FactCheck.org Rating: