Education Secretary Betsy DeVos used an outdated figure in claiming only 10% of school districts had “provided any kind of real curriculum and instruction program” after the coronavirus pandemic caused schools to shut down this spring. That was the case for 82 districts in late March, but by late April, 56% were doing so. In late May, the figure was 67%.

Those figures, from the Center on Reinventing Public Education, reflect the percentage of the 82 districts that provided formal curriculum and instruction.

Those districts, however, weren’t a nationally representative sample. Another analysis, conducted by the same organization and published in June, did include a statistically representative sample of U.S. school districts. It found, using publicly available information, that 33.5% expected all teachers to provide remote instruction, and another 13.2% expected some teachers to do so.

The Center on Reinventing Public Education, housed at the University of Washington Bothell, says it is “a nonpartisan research center open to all possible solutions to measurably improve outcomes for all students.” It says “parent choice is essential but not magic.”

DeVos made the claim during a July 8 coronavirus task force briefing in which she spoke about reopening schools this fall.

DeVos, July 8: There were a number of schools and districts across the country that did an awesome job of transitioning this spring. And there were a lot in which I and state school leaders were disappointed in that they didn’t figure out how to continue to serve their students. Too many of them just gave up. The Center for Reinventing Public Education said that only 10% across the board provided any kind of real curriculum and instruction program.

Robin Lake, the director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, did say that, as quoted in a March 31 article in U.S. News & World Report. That was shortly after 18 states, plus Washington, D.C., had ordered schools to close and another four recommended it on March 16, according to Education Week. In the days that followed, most other states ordered or recommended closures as well.

U.S. News & World Report, March 31: “Not many yet are providing what you’d consider a real coherent educational program,” says Robin Lake, the director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, where researchers compiled a database of how teachers and district leaders in 82 school districts that serve more than 9 million children are trying to salvage the school year.

“Only 10% across the board are providing any kind of real curriculum and instruction program, which is a little alarming given most of the experts are projecting we’re going to be in this mess for quite some time,” she says. “I don’t mean to pass judgement here. This is a hard, hard problem, but clearly we’re seeing a lot of variation.”

While not a representative sample of the entire country, the database does include dozens of the biggest school districts in the U.S., including New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Miami-Dade and more.

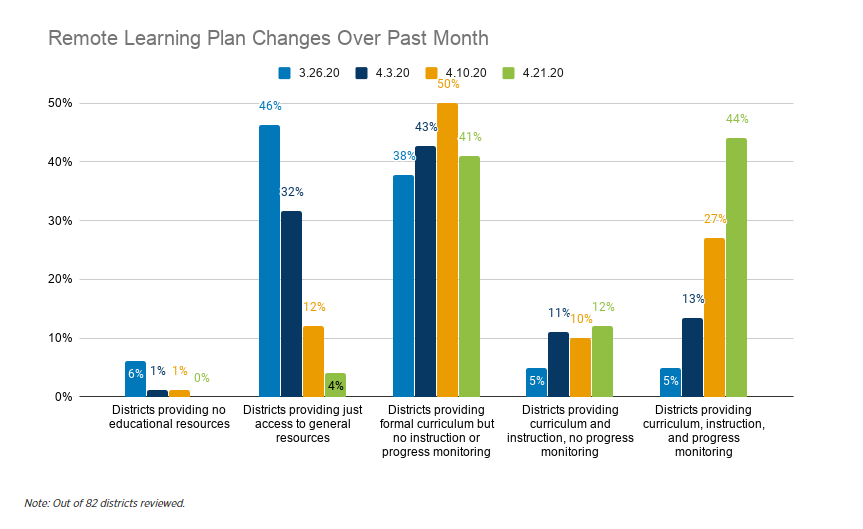

Lake based that comment on the results of an analysis of 82 mostly large school districts in urban areas. For the week of March 26, the center found 5% of those districts provided curriculum and instruction and another 5% provided curriculum, instruction and progress monitoring. That’s the source of Lake’s 10% figure, CRPE told FactCheck.org.

But as the chart below from CRPE shows, the number “rapidly improved since late March,” Travis Pillow, the editorial director and a spokesman for CRPE, said in an email to us. “By the end of the spring, the majority of the districts in our analysis were delivering curriculum, instruction and progress monitoring.”

The center’s chart shows that in the week of April 21, 12% of the districts were providing curriculum, instruction and no progress monitoring and 44% were providing all three. That means Lake’s 10% figure at the end of March rose to 56% by late April.

In an April 27 blog post on the center’s analysis, Lake and Bree Dusseault, practitioner-in-residence at the center, wrote: “Districts have come a long way” since the school closures began.

They noted, and the chart shows, that all districts were providing educational resources and nearly all were at least providing formal curriculum (even though 41% of the districts CRPE reviewed didn’t also provide instruction).

Pillow explained that some districts created packets of materials or online lessons for students but they didn’t expect teachers to provide instruction, either through the phone, live video or recorded lectures. “We were trying to determine whether districts were communicating an expectation that all three pieces of what education wonks call the ‘instructional core’ (students, teachers, content) would remain connected—that teachers were expected to help students make sense of the material,” he said. Teachers “might have been checking in with students or hosting social assemblies via Zoom, but when it came to teaching and learning, students and families were expected to be largely on their own with paper packets or online activities.”

By May 22, the percentage of the districts providing curriculum, instruction and progress monitoring had increased further — to 61%. Another 6% provided only curriculum and instruction, and 32% of those districts were at least providing formal curriculum.

However, since the 82-district analysis wasn’t a representative sample, CRPE conducted another analysis – of 477 districts, using statistical weighting to produce a nationally representative sample. That analysis, which relied on publicly available information, such as school districts’ websites and social media postings, “reveals a more sobering story,” CRPE said in a June report. It found 33.5% of districts expected all teachers to provide remote instruction this spring. Another 13.2% of districts expected some teachers to do so, such as only high school teachers.

The data was collected over a month — from April 6 to May 1, with some updates for missing information made during the week of May 4. The report notes that “these accounts should be considered a conservative take on districts’ responses,” since a small number — 14 districts — didn’t have any information about school closures on their websites or social media accounts and “some” offered limited information but clearly directly communicated with parents via other means.

In the sample, 85% of districts provided something – either curriculum packets, assignments posted in an online platform or guidance on using online learning software — and 57.9% expected teachers to monitor students’ progress or provide feedback for all or some of their students.

Pillow noted that setting an expectation isn’t the same as what actually happened with instruction: “We know there were schools and teachers in districts like Newark, NJ, that delivered instruction this spring even though their districts did not set that expectation,” he said. “On the other hand, we know there were places where instruction may have been expected, but large numbers of students were disconnected from school or not receiving instruction due to a lack of broadband or other challenges.”

So, while DeVos’ 10% figure later rose to 56% and then 67%, the better sample conservatively shows about one-third of school districts in the country expected all of their teachers to teach remotely. And another 13.2% expected some of their teachers to do so. We asked the Department of Education’s press office for comment on DeVos’ use of an outdated statistic, but we haven’t received a response.

Update, July 17: We received a response from the Education Department. Press Secretary Angela Morabito said in a statement: “The Secretary was recounting a study she had seen, which you have verified was accurate. It’s certainly a good thing that CRPE’s newest data shows more districts started to provide curriculum and instruction, but the fact remains that even at the end of April too many students still didn’t have access to education.”

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.