In the final weeks of his presidency, President Donald Trump has returned to the signature issue that brought him to the White House — his pledge to build “a beautiful, gorgeous, big wall” on the southern border. On two separate occasions, Trump has said he is “completing the wall, like I said I would” and that it is “almost finished.”

To be sure, the Trump administration has built hundreds of miles of border fencing, more than under any other president in American history. But by the end of Trump’s term in January, the length of fencing will be well short of what Trump promised repeatedly during the campaign or what his administration initially proposed when he took office.

Border experts say construction crews won’t come close to even finishing the work that is currently funded.

Most of the wall constructed to date has been replacement for existing dilapidated or inadequate fencing, despite earlier plans to build new barriers where none existed before. In 2018, an administration official testified that his agency would build 316 miles of new pedestrian barriers “in addition to what is there now.” But to date only about 40 miles of such new fencing have been built.

Other border experts warn not to minimize the impact of the replacement fencing. In some cases, the new barriers erected replaced fencing made from Vietnam-era landing mats. U.S. Customs and Border Protection also has replaced nearly 200 miles of vehicle barriers — the type that people could walk right through — with 30-foot-high steel bollards, lighting and other technology.

That’s a dramatic change. Below are before-and-after photos of vehicle barriers replaced by fencing in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona. The first was taken in April 2019, the second in January 2020:

|

|

But whether the wall is “almost finished” is another question. Part of the difficulty of measuring that is the ambiguity around what a completed wall would look like. Trump has constantly moved the goal posts on how long the wall should be, and no master plan for the project has ever been publicly released.

Those who have tracked the construction closely say fencing mostly has been built where there was least resistance, where the federal government already owned the land — particularly in Arizona and New Mexico. Far less has been built in areas of Texas, especially, where private landowners have fought condemnation of their land in the courts.

What has resulted, border experts say, is a patchwork of fencing. Nonetheless, with no publicly shared benchmarks for “completion” of the wall, Trump has declared near-victory.

“You know, we’re completing the wall, like I said I would,” Trump said in an interview on Fox News on Nov. 29. “Everyone said, you would never be able to do it.”

At a Dec. 5 rally in Georgia, Trump said, “They even want to take down the wall. … I heard him [President-elect Joe Biden] say it the other day, ‘We will take down the wall.’ We have the strongest border we’ve ever had now. We’re almost finished with the wall.”

As we have written, Biden has not said he plans to “take down the wall,” contrary to Trump’s claim. But Biden did vow in August that, if elected, “there will not be another foot of wall construction in my administration.”

According to a CBP status report, the U.S. has constructed 438 miles of “border wall system” under Trump, as of Dec. 18. Most of that, 365 miles of it, as we said, is replacement for primary or secondary fencing that was dilapidated or of outdated design. In addition, 40 miles of new primary wall and 33 miles of secondary wall have been built in locations where there were no barriers before.

So the footprint of the wall is 40 miles longer than it was before Trump took office.

CBP says it has funding in place to construct another 241 miles of fencing where there were no barriers before. But border experts say most of that is not going to get built.

According to CBP updates, in the last three months about 31 miles of new wall have been constructed in areas where there was no barrier before. At that rate, and assuming Biden immediately puts a halt to all new wall construction as promised, the administration will complete less than a quarter of the new miles for which it has funding — and that will be well short of the new miles of wall Trump had originally promised.

What did Trump promise?

Although the 2016 Republican platform stated, “The border wall must cover the entirety of the southern border and must be sufficient to stop both vehicular and pedestrian traffic,” that’s not actually what Trump talked about during the campaign.

At the time, Trump consistently talked about needing 1,000 miles of wall. Here are just a few examples over a 10-month period during the campaign:

- “Here, we actually need 1,000 because we have natural barriers. So we need 1,000.” — Trump during the third Republican primary debate, on Oct. 28, 2015.

- “Now, it’s 2,000 miles but we need 1,000 miles of wall. Nothing. It’s nothing. I will have the most gorgeous wall you’ve ever seen. Someday, when I’m gone they’ll name it the Trump wall.” — Trump during a campaign speech in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on April 21, 2016.

- “We have 2,000 miles [of border] of which we really need 1,000 miles [of wall] because you have a lot of natural barriers — lot of natural barriers. So you need 1,000. — Trump at a rally in Abingdon, Virginia, on Aug. 10, 2016.

Given that Trump inherited about 650 miles of barriers, that would mean building another 350 miles (in addition to any replacement fencing).

But once Trump was elected, he began to move the goal posts — from 1,000 miles to 900 to 800 to 700 and even less.

- “And remember this, it’s a 2,000 mile border, but you don’t need 2,000 miles of wall because you have a lot of natural barriers. You have mountains. You have some rivers that are violent and vicious. You have some areas that are so far away that you don’t really have people crossing. So you don’t need that. But you’ll need anywhere from 700 to 900 miles.” — Trump in a July 12, 2017, interview.

- “But we need to have a wall that’s about 800 miles — 700 to 800 miles of the 2,000-mile stretch. We have a lot of natural boundaries.” — Trump in remarks at the White House on April 3, 2018.

- “We need about 700 miles of wall. It’s 2,000 miles. We need about 700 miles of wall. We’re getting it.” — Trump at a rally in Nashville, Tennessee, on May 29, 2018.

- “We are going to do about 537 miles altogether. And it will give a complete, beautiful wall on our southern border that’s really helped.” — Trump in a July 23, 2020, interview.

“We do not need 2,000 miles of concrete wall from sea to shining sea — we never did; we never proposed that; we never wanted that — because we have barriers at the border where natural structures are as good as anything that we can build,” Trump said in remarks from the White House on Jan. 25, 2019. “They’re already there. They’ve been there for millions of years. Our proposed structures will be in predetermined high-risk locations that have been specifically identified by the Border Patrol to stop illicit flows of people and drugs.”

But is the wall being built in “predetermined high-risk locations”?

What was the Trump administration’s plan?

In his executive order on border security issued on Jan. 25, 2017, just days after he was inaugurated, Trump called on the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security to “produce a comprehensive study of the security of the southern border, to be completed within 180 days of this order, that shall include the current state of southern border security, all geophysical and topographical aspects of the southern border, the availability of Federal and State resources necessary to achieve complete operational control of the southern border, and a strategy to obtain and maintain complete operational control of the southern border.”

A July 2020 report from the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Homeland Security said the report ultimately submitted by CBP — the Comprehensive Southern Border Study and Strategy — was four months late (after the 180 deadline imposed by the executive order). The IG said the plan was inadequate because CBP didn’t demonstrate it could acquire the land necessary to carry out its plan and the agency didn’t justify the priorities it set out in the plan.

Specifically, it states that CBP “did not conduct an Analysis of Alternatives to assess and select the most effective, appropriate, and affordable solutions to obtain operational control of the southern border as directed, but instead relied on prior outdated border solutions to identify materiel alternatives for meeting its mission requirement; and … did not use a sound, well-documented methodology to identify and prioritize investments in areas along the border that would best benefit from physical barriers.”

The CBP report was never released publicly.

During a congressional hearing on March 15, 2018, Rep. Martha McSally said that in late 2017, Congress asked CBP leadership “to provide Congress with a list of what they needed to adequately secure the border.”

In response, in early January 2018, CBP produced a document called “Critical CBP Requirements to Improve Border Security,” which was also never publicly released. According to CNN, which obtained the documents, CBP laid out a long-term vision for “about 864 miles of new wall and about 1,163 miles of replacement or secondary wall” and asked for $18 billion over 10 years to build 722 miles of border wall, including “about 316 new miles of primary structure and about 407 miles of replacement and secondary wall.”

At the March 15, 2018, committee hearing, Ronald D. Vitiello, acting deputy commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, confirmed that the CBP document called for constructing 316 miles of new pedestrian fencing, “in addition to what is there now.” In other words, that was in addition to the 654 miles of existing border barriers.

Again, to date, 40 miles of new fencing have been constructed where there were no barriers before.

Where did construction take place?

There also have been questions raised about CBP’s methods for determining where new barriers should be located.

A Government Accountability Office report published in July 2019 found that CBP’s 2018 Border Security Improvement Plan “doesn’t explain how projects will address the highest priority security needs.”

The Center for Biological Diversity’s Laiken Jordahl, who opposes fencing construction, told us in a phone interview that the project always has been shrouded in secrecy, and CBP has not shared with the public any analysis of where it thinks a wall should be built for maximum impact.

“There’s never been any sort of strategic planning,” Jordahl said. “There certainly hasn’t been anything presented to the general public” about where CBP intends to build the wall and why. “From Day 1, it has never been about tactics. It has been a theatrical campaign from the beginning.”

Rather than building fencing in areas identified as being of the greatest need, he said, the Trump administration has done most of the construction in areas of least resistance.

“They are building where they can,” Jordahl said.

Much of the construction has been to replace dilapidated or inadequate fencing in New Mexico, Arizona and California, where the government owns the Roosevelt Easement, a 60-foot wide strip of land along the U.S.-Mexico border in those three states.

“He has completely changed the landscape of the Arizona and New Mexico border,” Jordahl said. “It has had absolutely disastrous environmental impacts.”

It has destroyed the habitat for animals like ocelots, pronghorns and javelinas, all of which need room to roam, Jordahl said. It has cut off the genetic interchange of gray wolves on either side of the border, threatening their survival. And it has hampered the ability of jaguars to recolonize in the U.S.

Scott Nicol, co-chairman of the Sierra Club’s Borderlands team, told us via email: “More miles have been completed there since there is no need to condemn private property, but the miles under construction are in the most rugged, technically challenging, and environmentally destructive locations.”

But Trump’s claim that the wall is “almost finished” is “absolutely not true, particularly in South Texas,” where large swaths of the borderlands are privately owned, Nicol said. In South Texas, Nicol said, “the need to acquire property on which to build the border wall has stymied construction” as landowners have tied up the government in the courts.

According to a GAO analysis issued in November, as of July 2020 the federal government had acquired 135 tracts of privately owned land, but was still working to acquire 991 additional tracts, almost all of them in the Rio Grande Valley and Laredo sectors in South Texas.

“So nothing has been built on any of those [unacquired] properties,” Nicol said.

“The construction that has occurred in the RGV sector (nothing has gone up in the Laredo sector yet) first targeted U.S. Fish and Wildlife refuge properties that are part of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge system,” Nicol said. “That is tremendously environmentally destructive, but it does not translate into more than a mile or so of wall in multiple disconnected segments. There have also been some landowners whose property has been taken where walls have been built.”

“Contractors … have built on land as soon as the government acquires it, but due to the time it takes to condemn that means that only a fraction of these walls have been built,” Nicol said. “So, for example, the Southwest Valley Constructors contract is for 11.45 miles of wall, but they have only been able to build 2 or maybe 3 miles in 6 or 7 disconnected, relatively short spans. The same applies for the other contracts in Hidalgo County [Texas], which is in the middle of the RGV sector. Cameron County [Texas] has seen no construction, and Starr [County, Texas] has seen 3 or 4 miles total.”

According to the GAO report, 107 miles of new border wall are slated to be built in the Rio Grande Valley, but Nicol said, “Right now a total of 6 or 7 miles are up, and those are scattered rather than completed contracts.” The Laredo sector is supposed to get 123 miles of new fencing, but Nicol said it has not yet gotten any.

“So not even close to being finished,” Nicol said.

Gil Kerlikowske, who served as CBP commissioner under then-President Barack Obama, said that the issues with acquiring property from private landowners in Texas means the fence is not going up in areas where there are the most illegal border crossings.

“The areas where a large number of people cross into the U.S. is the RGV (McAllen, TX area),” Kerlikowske told us via email. “It is much more difficult to erect a barrier there because of private land ownership, a changing Rio Grande river, and agriculture. So the area where you could justify the need is the one neglected.”

Activists like Jordahl and Nicol are counting on Biden to immediately put a stop to fence construction long before the current contracts are completed.

The Center for Biological Diversity and the Sierra Club were among the 100 groups that sent a letter last month to the Biden transition team asking the president-elect to “take immediate action to order the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, and Department of Justice to halt all construction and land acquisition efforts for Trump’s border wall on your first day in office.”

How much did it cost and who paid?

Trump, of course, repeatedly promised that Mexico would pay for the wall. And that hasn’t happened, despite Trump’s false claims that Mexico is paying somehow through the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement or with a border toll.

According to CBP data provided to FactCheck.org, the Trump administration secured a total of $15 billion during his presidency for wall construction. Some of it was appropriated in annual budgets by Congress, and some was diverted by Trump from counternarcotics and military construction funding. But it has all been borne by American taxpayers.

The figure committed to date for wall construction — $15 billion — suggests the wall Trump got is well short of what he wanted.

And it is unlikely the Trump administration will be able to spend even that much. According to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ estimates reviewed by the Washington Post, there will be about $3.3 billion in unused border barrier funding when Biden takes office. If Biden immediately stops construction as promised, it would cost the U.S. about $700 million to terminate those contracts, saving the U.S. government about $2.6 billion.

“The administration has also said that with the $15 billion in funding it allotted for the wall, it could build 738 miles,” Sarah Pierce, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, told us via email. “So, no, the total amount of wall that the administration had planned to construct is not close to being completed and will not be completed.”

The WALL Act of 2019, introduced by Republican Sen. James Inhofe in January 2019 and co-sponsored by five other Republicans, sought $25 billion for wall construction, an attempt to fully fund the wall. The bill never went anywhere, but it is another indication of how far short the president has come to building the wall he promised.

The recently agreed upon pandemic relief bill includes $1.375 billion for “the construction of barrier system,” the same amount Congress has appropriated the last three years. A House Democratic aide told us the funding has five years of availability, so that none of the funding would need to be obligated until fiscal year 2025. In addition, Democrats were able to strike language used in prior years that required funding to be used for new border wall construction, which would have significantly tied Biden’s hands, the aide said.

Even if the Trump administration were able to obligate all of this funding for new border wall prior to Biden’s inauguration on Jan. 20, Biden would be able to cancel those contracts with little loss of funding. The wording of the bill would also give Biden the discretion to use any remaining funds for “barrier system,” including technology, roads and lighting for already constructed border barriers, the aide said.

What kind of ‘wall’ was built?

The type of wall Trump promised to build also has evolved over time.

During the 2016 campaign, Trump once talked about a wall made of precast concrete slabs. After he became president, Trump commissioned wall prototypes, many of them of solid concrete construction. But the new fencing being built doesn’t resemble any of the prototypes. Rather, Congress only authorized Trump to build the same see-through steel bollard fencing previously used for the wall.

Gone, too, are the arguments over the vocabulary used — fencing or wall. It once made a difference to Trump. During the 2016 campaign, for example, Trump lambasted Republican primary opponent Jeb Bush for calling his proposal a fence. “It’s not a fence, Jeb,” he wrote. “It’s a WALL, and there’s a BIG difference!”

But during his presidency, Trump has dropped that distinction. Not coincidentally, it was dropped around the time Congress forced him to accept “operationally effective designs deployed as of the date of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, [May 5, 2017] such as currently deployed steel bollard designs, that prioritize agent safety.”

“The walls we are building are not medieval walls,” Trump said in remarks from the White House on Jan. 25, 2019. “They are smart walls designed to meet the needs of frontline border agents, and are operationally effective. These barriers are made of steel, have see-through visibility, which is very important, and are equipped with sensors, monitors, and cutting-edge technology, including state-of-the-art drones.”

But words used to describe the fence are still important to the administration.

Last January, Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Chad Wolf took issue with characterizing much of the fence construction as “replacement wall.”

“One thing I want to emphasize is that every inch of the 100 miles that we have constructed is new border wall system,” Wolf said. “It’s not so-called replacement wall, as some of our critics claimed. It is new wall.”

According to a Washington Post story in January, “Nearly all of the 100 miles of new fencing completed thus far is labeled ‘replacement barrier’ by CBP, but the White House has asked the agency to stop using that term because it sounds like less of an accomplishment.”

A January Congressional Research Service report on border barrier funding said the debate over nomenclature misses the point.

“Is the Administration ‘building the wall,’ or is it ‘just replacing existing fences?’ Framing the debate on barrier or wall building at the border using these extremes often does not capture the complexity of the situation, in terms of what CBP states the barriers can be expected to do and the realities of the terrain and geography of the border,” the authors stated. “Much of the current wave of construction — whether new or replacement barriers — is 18- to 30-foot high reinforced bollard fencing. It poses a formidable barrier, but it is not the high, thick masonry structure that most dictionaries term a ‘wall.’”

Whatever one wants to call it, CBP has accelerated the pace of construction to get as much finished as possible before Biden takes office. U.S. attorneys have also stepped up their efforts to condemn property in Texas for the wall. Some who live near the border oppose that construction, and others say it has made their communities safer.

But, as we have said, even if Trump reached his goal of building 450 miles of wall before his term is over, it wouldn’t be “finished,” at least not to the point CBP has indicated in previous reports is necessary to “achieve complete operational control of the southern border,” the goal outlined in Trump’s post-inaugural executive order. Nor will it be anywhere close to what Trump promised during his 2016 campaign.

Has it been effective?

Back in August, when Trump was accepting the Republican nomination, he boasted: “The wall will soon be complete, and it is working beyond our wildest expectations.”

But it may be years before we are able to tell how effective the wall has been at stopping illegal immigration. Many factors that have nothing to do with the wall — COVID-19, the economy, civil unrest — all play a role in attempted illegal border crossings.

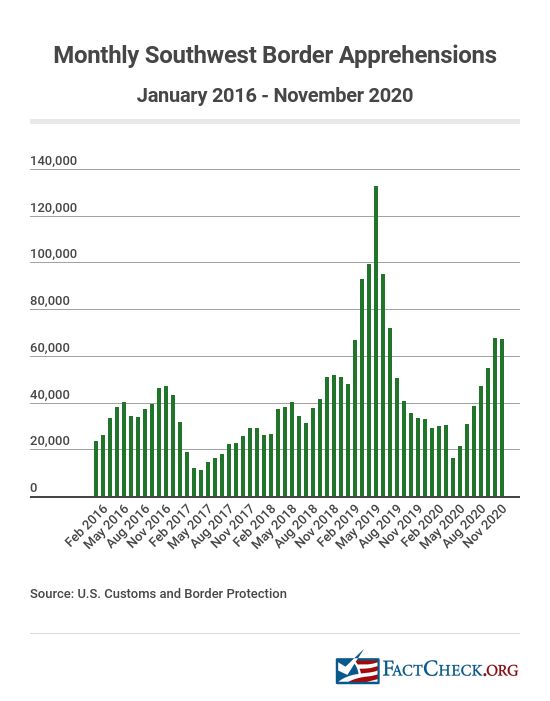

Experts use figures on border apprehensions to gauge the level of illegal border crossings. The data from CBP present a mixed bag when it comes to making Trump’s case.

Border apprehensions spiked in fiscal year 2019, and then fell by about half in fiscal 2020, which ended on Sept. 30. It is impossible to tease out how much of that drop may be as a result of the new barriers constructed under Trump, but a Pew Research Center report documenting the decline attributed it mostly to a worldwide decrease in the movement of migrants due to the COVID-19 outbreak, and governments fully or partially closing their borders as a result.

Most immigrants who cross into the U.S. illegally come from Mexico and Central American countries that have passed measures restricting the movements of their residents due to COVID-19.

Meanwhile, southwest border apprehensions for October and November, the first two months of fiscal year 2021, have crept back up, topping just over 67,000 each month. That’s higher than October and November 2016 (when there were about 46,000 and 47,000 apprehensions, respectively), before Trump took office.

Update, Feb. 16: According to a CBP status report dated Jan. 22, two days after Trump left office, the U.S. constructed 458 miles of “border wall system” under Trump. That included 373 miles of replacement barriers for primary or secondary fencing, and 52 miles of primary wall and 33 miles of secondary wall in locations where there were no barriers before.

Biden did halt construction of new border barriers immediately upon taking office. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said it “suspended all bollard barrier and gate construction January 21, 2021, and suspended all work on border infrastructure January 23, 2021.”

Editor’s Note: Please consider a donation to FactCheck.org. We do not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.