After the Senate passed its version of the American Rescue Plan Act, Republican Rep. Liz Cheney claimed “the result of that package is going to be middle-class tax increases.” The legislation cuts middle-income taxes.

Cheney assumes Congress will one day pay for the law with middle-class tax hikes. But that’s a questionable assumption, and one reminiscent of the way each party reacts when the other spends money.

Congress faces a mountain of debt it one day should start paying for, and there’s little indication it has the political desire to do so, let alone with “middle-class tax increases.”

Howard Gleckman, a senior fellow in the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, told us it seemed there was “no political will to do what Rep. Cheney is talking about” — raising middle-income taxes — and no real interest in Congress in paying for anything. “We have been spending money and cutting taxes now for a decade and no one has shown any interest in paying for it.”

American Rescue Plan Tax Cuts

Cheney made her claim in a March 9 Republican House press conference. She said the American Rescue Plan Act “is a real tragedy. When you look at that package, we know that the result of that package is going to be middle-class tax increases.”

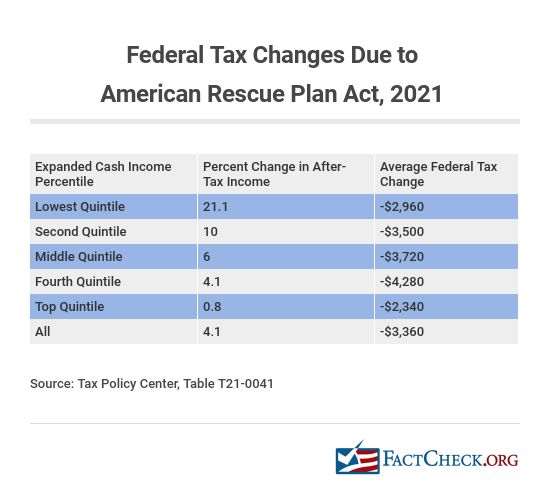

The legislation, which Biden signed into law on March 11, provides an average tax cut to middle-income earners of $3,720 this year, according to an analysis by the Tax Policy Center. That’s for tax filers earning between $51,000 and $91,100 a year.

The legislation, which, among other measures, includes direct stimulus payments and increased earned income and child tax credits, provides larger average tax cuts to the bottom 80% of income earners than to the top quintile. The only effective tax increase falls on the top 1%, and in particular the top 0.1%, whose after-tax income, on average, rises by an estimated $970 due to the allocation of corporate tax increases to shareholders. Those in the top 0.1% earn more than $3.5 million.

The corporate tax increase involves interest costs for multinational companies and would raise $22.3 billion over 10 years, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates.

Will Congress Pay for the New Spending, and How?

A spokesperson for Cheney told us she meant that middle-class tax increases would be required in order to pay for the Democrats’ COVID-19 relief package. The legislation carries a cost of $1.9 trillion over 10 years, with the bulk of the spending in 2021, the Congressional Budget Office estimates.

The spokesperson also pointed to Sen. Joe Manchin’s late February comment that “everything’s open for discussion,” in speaking of a repeal of the 2017 GOP tax cuts.

But as a Feb. 25 article in The Hill made clear, Democrats aren’t united on whether a repeal of those tax cuts should be done in the near future, nor on whether an anticipated infrastructure spending bill should include some kind of tax increases to cover the cost. Manchin told a business group that “nobody likes taxes,” but “sooner or later, we’ve got to pay.”

But Democrats have talked about tax increases on the wealthy, not those in the middle of the pack.

Sen. Ron Wyden, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, has been working on tax legislation, mentioning measures such as capital gains rates and taxes on inherited estates.

Biden has said he wants to repeal the GOP tax law, signed by then-President Donald Trump at the end of 2017, but he pledged not to raise taxes on anyone making under $400,000.

Democrats, meanwhile, have continued to misleadingly describe the Trump tax measure as a $1.9 trillion bill that gave “83% of the benefits to the top 1%,” as House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said before the final passage of the American Rescue Plan Act.

As we’ve written, that’s true for 2027, only because most of the individual income tax changes in the law expire by then. Two years earlier, in 2025, 25% of the tax cuts go to the top 1%. The tax law cost an estimated $1.9 trillion over 10 years, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

But just as Congress didn’t pay for that law, it’s not clear if or how it will pay for the American Rescue Plan Act either — or earlier COVID-19 relief measures that totaled $4 trillion in spending. And if Congress does raise taxes, Gleckman told us, who’s to say which part of the deficit-spending that revenue is meant to cover?

Gleckman said it was an “open question” as to whether Congress really has to pay for the latest COVID-19 relief act. “Nobody shows interest in paying for anything these days,” he said.

And “if we do pay for it, who pays for it?” he added. Mathematically, he said, there are ways to do it besides raising taxes on those in the middle of income earners. Gleckman argued in an April 2020 post that, politically speaking, Congress would have to look at other means besides federal income taxes to pay for coronavirus relief.

But with so much public debt — $21.8 trillion — there would be no way of knowing which causes of the debt Congress would be addressing if it does raise revenue in the future.

Maya MacGuineas, president of the budget watchdog group Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, told CNN on Jan. 13 that deficit spending during this time is necessary to boost the economy. But eventually, Congress should do something about the rising debt.

“And yes, I worry about the debt and the debt is too high, but the first thing we have to do is deficit spend till we can get the economy strong enough to then pivot and worry about some of those other longer-term issues,” said MacGuineas, who recently criticized the American Rescue Plan Act for including “hundreds of billions of dollars where it isn’t needed.”

In the CNN interview, she said, “I don’t think we should start raising taxes right now while the economy is weak,” but something could be done once “the economy is strong enough.”

On the campaign trail, Biden had proposed tax increases on upper-income earners that would raise $4 trillion over 10 years, as estimated by the Tax Policy Center. But Biden said the money could fund infrastructure, higher education and more.

“The Biden campaign and the president-elect have been very clear that they want to target those revenue raisers to people, corporations and people on the higher end of the income spectrum,” MacGuineas said. “That said, they aren’t enough to cover the entire cost of the very large policy plan that he has laid out, from green infrastructure to education to health care. So as the economy stabilizes and we have to get much more serious about dealing with the mountain of debt that we have at near record levels, we’ll have to fill in some of the gap with even more offsets if they want to have as expansive an agenda as they’re talking about.”

Cheney’s claim that the Democrats’ spending bill would eventually cause a “middle-class” tax hike reminds us of Democrats claiming Republican plans would lead to similarly unpopular policies.

For instance, in 2018, a Democratic ad claimed that in order to pay for the GOP tax cut law, “there’s a plan to cut Medicare for seniors.” Some lawmakers had talked about reducing the growth of Medicare in order to lower deficits, but there was no plan to cut the program.

And back in 2012, Democrats made the groundless claim that then-Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney would increase middle-class taxes in order to pay for the rest of this tax cut proposal. That was based on a Tax Policy Center analysis that said it was mathematically impossible for Romney to reduce tax rates across the board without losing revenue – not that he would raise middle-class taxes.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.