The United States continues to import a smaller amount of its petroleum from the Middle East, part of a decadeslong trend that has continued under President Joe Biden.

The U.S. gets most of its imported oil from Canada. About 9.8% of U.S. petroleum imports (most of it crude oil) came from Persian Gulf countries in 2020, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration data. That has dropped to an average of about 6.6% in the first five months of 2021.

But at a rally in Alabama on Aug. 21, former President Donald Trump said he had gotten the U.S. to a point where “we didn’t need the Middle East.” And now, he said, “we’re going back to them asking them for help.”

Republican Rep. Lauren Boebert similarly tweeted that “Under Trump, we exported American energy. Under Biden, we are back to being dependent on the Middle East again.”

The help from the “Middle East” cited by Trump is a reference to a White House statement that urged OPEC to pump more oil to bring down the price of gasoline in the U.S.

“While OPEC+ recently agreed to production increases, these increases will not fully offset previous production cuts that OPEC+ imposed during the pandemic until well into 2022,” National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said in the Aug. 11 statement. “At a critical moment in the global recovery, this is simply not enough.”

The announcement was criticized by some conservatives and progressives. Trump described it as Biden now “begging OPEC for more production to please send energy our way.”

Although Trump and Boebert used the broad term “energy,” Boebert’s press secretary, Jake Settle, told us Boebert was referring to the balance between U.S. imports and exports of petroleum.

Petroleum Imports and Exports

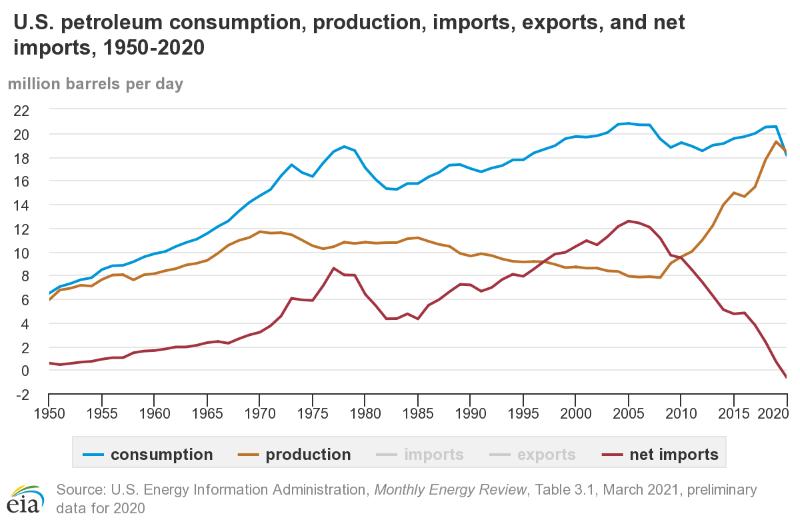

An EIA report on oil and petroleum products notes that the U.S. exported about 8.5 million barrels per day of petroleum in 2020, while importing about 7.9 million barrels per day, “making the United States a net annual petroleum exporter for the first time since at least 1949.”

Settle cited an EIA forecast released on Feb. 17 that projected “the U.S. will import more petroleum than it exports in 2021 and 2022.”

“Instead of deregulating the American energy market, Biden’s National Security Advisor called on OPEC to increase production of oil,” Settle said in an email. “Instead of continuing President Trump’s policies that moved America towards energy independence, the Biden administration is moving America back to relying on OPEC and the Middle East for energy security.”

The EIA report, however, made no mention of any Biden policies being responsible for the shift in balance from being a net exporter of petroleum in 2020 to a net importer in 2021 and 2022. Rather, the report in February simply said it is “largely because of declines in domestic crude oil production and corresponding increases in crude oil imports.”

The decline in domestic crude oil production came “as result of a decline in drilling activity related to low oil prices,” according to an EIA report in January. “Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic led to supply and demand disruptions,” the report noted.

In fact, the EIA has been forecasting that the U.S. would import more petroleum than it exports in 2021 and 2022 ever since April 2020 — in its first monthly forecast to consider the expected economic effects of the U.S. COVID-19 response measures announced in March of that year (and long before Trump left office).

EIA, Short-Term Energy Outlook, April 2020: EIA assumes significantly lower levels of U.S. liquid fuels consumption during much of 2020 as a result of the disruptions to economic and business activity because of COVID-19 and the strict containment measures that have dramatically reduced all forms of travel. These impacts are expected to be most pronounced during the second quarter of 2020, when most containment measures and wide-scale reductions in business activity are assumed to be in place. EIA expects these impacts to persist through most of 2020, but in the second half of 2020, EIA expects liquid fuels consumption will gradually increase from these low levels as some business activity resumes and stay-at-home orders gradually ease. … The rise in U.S. liquid fuels consumption in the second half of 2020 drives the United States to return to being a net importer of crude oil and petroleum products in the third quarter of 2020 and remaining a net importer in most months through the end of the forecast period.

In other words, global forces related to the pandemic — not federal policy from the U.S. — was expected to cause the shift in petroleum imports and exports.

An Aug. 16 letter led by Sen. James Inhofe, and signed by 23 other Republican senators, criticized the Biden administration for reaching out to OPEC to increase oil supplies “when America has sufficient domestic supply and reserves to increase output which would reduce gasoline prices.”

The letter, in part, blamed Biden’s decision to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline (which would increase Canadian oil production) and an executive order issued on Jan. 27, pausing “new oil and natural gas leases on public lands or in offshore waters pending completion of a comprehensive review and reconsideration of Federal oil and gas permitting and leasing practices.”

“We’re going to review and reset the oil and gas leasing program,” Biden said that day.

But in March, when the EIA looked into the effect of the Biden administration’s federal leasing moratorium, which allows oil producers to continue operations under existing leases, the EIA concluded the overall effect would be vanishingly small. The moratorium applies only to new leases.

“No effects will likely occur until 2022 because there is roughly a minimum eight-to-ten month delay from leasing to production in onshore areas and longer in offshore areas,” the EIA report states. “Incorporating this change reduced U.S. crude oil production by less than 0.1 million barrels per day on average in 2022.”

To put that in perspective, the U.S. produced about 11.2 million barrels of crude oil per day in May. So, the effect of the moratorium — which a federal judge suspended in June, anyway — was forecast to result in a less than 1% reduction in U.S. oil production next year.

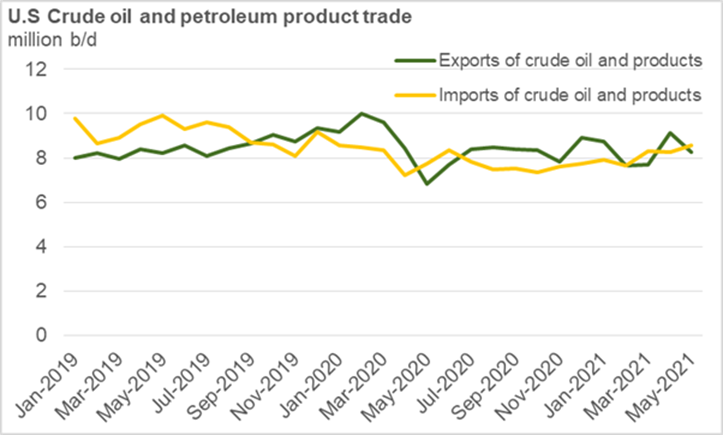

As the EIA graph below shows, in early 2020, right before the pandemic, exports were higher than imports. Then exports fell sharply once the pandemic hit. Meanwhile, imports stayed relatively constant.

Looking at the big picture, however, the trend lines show a dramatic decrease in net petroleum imports going back to the mid-2000s, as well as a steady closing of the gap between U.S. petroleum consumption and production.

The forecast for the U.S. to slightly dip below the net importer/exporter line in the first year of Biden’s presidency would have little effect on those larger trends — certainly not to the point where the U.S. would suddenly be more dependent on Middle East oil, after supposed independence just months ago.

Imports from Persian Gulf Countries

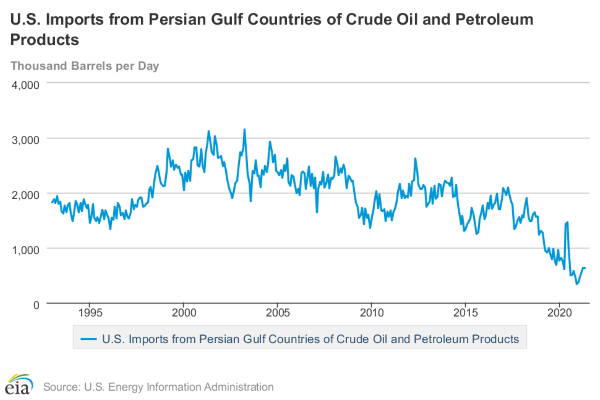

The U.S. has imported less oil from the Persian Gulf region under Biden than under Trump. And the share of oil imported from the Middle East — which has been dropping for decades — is continuing to decline.

The U.S. imported an average of 536,400 barrels of crude oil and petroleum products a day from Persian Gulf countries in the first five months of 2021, according to EIA data. That’s a 30% decline from the monthly average of 767,166 barrels a day that the U.S. imported from those countries in 2020, and a 44% decline in average monthly imports compared with 2019. (The Persian Gulf countries are Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.)

In 2020, about 9.8% of U.S. petroleum imports (most of it crude oil) came from Persian Gulf countries, according to the EIA. That has dropped to an average of about 6.6% through the first five months of 2021.

But Persian Gulf countries still produce nearly a third of the world’s petroleum (27.5% in April, according to the most recent EIA data), and so hold large influence on the global price of oil. The U.S., by comparison, produced about 20% of the world’s petroleum in April.

Imports from OPEC Countries

If Trump and Boebert meant OPEC nations rather than Persian Gulf nations, the story is the same.

There are 15 OPEC nations, including Middle East countries such as Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, but also non-Middle East countries such as Nigeria, Ecuador and Venezuela. These countries, which produce about 40% of the world’s oil, often work in coordination as a cartel to influence the global price of oil.

The average monthly imports from OPEC nations to the U.S. in 2021 have declined a little over 10% compared to the monthly average in 2020 (see Table 3.3a). Overall, about 11.3% of the oil the U.S. imported in 2020 came from OPEC nations. It has been about 9.8% in the first five months of 2021.

That is part of a long-term trend.

As the EIA wrote in May, “Between 2005 and 2020, U.S. crude oil imports from OPEC members decreased rapidly, but imports from non-OPEC members remained relatively high. In particular, U.S. crude oil imports from Canada more than doubled to average 3.6 million b/d in 2020, which was more than the combined total of crude oil imports from all other countries.”

Indeed, the EIA wrote in another report in May, “Canada’s share of total U.S. crude oil imports increased, reaching a record-high share of 61% in 2020.” The report notes U.S. crude oil imports from Canada have been down only slightly in 2021, as of April 23. “At the same time, imports from selected members of OPEC are down by 46%,” the report states. “Voluntary OPEC production cuts are contributing to lower U.S. crude oil imports from OPEC members.”

Nonetheless, OPEC remains a main driver of world oil prices, which affects the price of gasoline at American gas stations, too.

“Since OPEC was established in 1960, it has played a major market role in influencing the price of oil (and the subsequent price of energy products like gasoline),” Devin C. Gladden, manager of federal affairs for AAA National told us via email. “No presidential or federal policies since that time, aside from a crude oil export ban and its lifting, have been able to curb the impact of OPEC on global energy prices.”

The Energy Policy and Conservation Act passed by Congress and signed by President Gerald Ford in 1975, banned nearly all exports of U.S. crude oil. Congress lifted the ban in 2015 under then-President Barack Obama.

The average gross exports so far during the Biden administration are higher than the average during the Trump administration, Samantha Gross, director of the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institution and the director of the Department of Energy’s Office of International Climate and Clean Energy under Obama, told us in an email.

“But the real issue here is way beyond anything either administration did – it’s about global oil prices,” Gross said. “Presidents can’t do much to control those, they are set in the global marketplace, although politicians suffer when gasoline prices rise. As the swing producers, OPEC decisions make a difference here and that’s why presidents often jawbone OPEC to produce more to bring oil prices down. It’s not because we are any more dependent on the Middle East than we were last year.”

“OPEC has been reluctant to increase production too much as the global economy is recovering from Covid,” Gross added in her email. “They were hurt when prices took a nosedive when the pandemic started and don’t want to get ahead of the market. US producers pulled back too and are now ramping up production again. None of this has anything to do with Trump or Biden policies – it’s all about markets and prices.”

We should note that back in 2019, Trump, too, was criticizing OPEC for artificially restraining production to drive up global gas prices.

“OPEC, please relax and take it easy. World cannot take a price hike — fragile!” the then-president tweeted in February 2019.

But in 2020, as the pandemic hit, Trump was lobbying OPEC in the other direction, urging OPEC members to cut production because the lower global prices were hurting American producers.

In both cases, Trump and Biden acknowledged the power of OPEC to influence the global petroleum market, even though it supplies relatively little oil to the U.S.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.