SciCheck Digest

Raw numbers of hospitalizations or deaths among those who are vaccinated are not a good indicator of whether vaccines are effective. If the large majority of a population is vaccinated, it’s not surprising if most deaths are among the vaccinated. But social media posts misuse data from the U.K. to suggest the COVID-19 vaccines don’t work.

Full Story

Epidemiologists and biostatistics experts have been cautioning that as more and more of a population gets vaccinated, we’ll likely see more deaths from COVID-19 among the vaccinated. It’s simply math. The vaccines aren’t 100% effective — no vaccine is — so some deaths are expected. And if there are relatively few people still unvaccinated, the raw numbers of deaths are likely to show more deaths among the vaccinated.

“Consider the hypothetical world where absolutely everyone had received a less than perfect vaccine. Although the death rate would be low, everyone who died would have been fully vaccinated,” David Spiegelhalter, chair of the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication at the University of Cambridge, and Anthony Masters, statistical ambassador for the Royal Statistical Society, wrote in late June for a story published in the London-based Guardian.

“Consider the hypothetical world where absolutely everyone had received a less than perfect vaccine. Although the death rate would be low, everyone who died would have been fully vaccinated,” David Spiegelhalter, chair of the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication at the University of Cambridge, and Anthony Masters, statistical ambassador for the Royal Statistical Society, wrote in late June for a story published in the London-based Guardian.

The headline on that piece: “Why most people who now die with Covid in England have had a vaccination.” Spiegelhalter and Masters cautioned: “Don’t think of this as a bad sign, it’s exactly what’s expected from an effective but imperfect jab.”

Yet, months later, misleading social media posts are highlighting data from the U.K., suggesting the numbers of deaths show something is wrong.

“BE IN THE KNOW: the vast majority of people (7 out of 10) who died from the COVID-19 virus in the UK were fully vaccinated,” one Facebook post reads, accompanied by a clip of Alex Berenson citing the data on “The Joe Rogan Experience” podcast on Oct. 12. Berenson, an author and former New York Times reporter, has been banned from Twitter for violating its rules on COVID-19 misinformation. We wrote about one of his tweets on the COVID-19 vaccines earlier this year. In the Facebook clip, Berenson correctly cites the U.K. numbers but presents them as something surprising.

“And I have to keep saying this to people because they almost don’t believe it. In the U.K. 70-plus percent of the people who die now from COVID are fully vaccinated,” Berenson said. “It’s not a conspiracy theory. It’s not somebody saying, Oh, I heard this from my cousin. It’s in British government document from the U.K. Public Health England.”

The 70% figure is correct. But again, those are raw numbers, among a highly vaccinated population. In its week 38 report, Public Health England — which has been replaced by the UK Health Security Agency — reported there were 3,158 deaths from COVID-19 from Aug. 23 through Sept. 19 and 2,284 of those individuals (72.3%) had received their second vaccine shot at least 14 days earlier. However, the same report shows vaccination rates approaching or exceeding 90% for age groups 60 and older, the group that accounts for 86.5% of all deaths in that time period.

Overall, 77.3% of the U.K. population 12 and older had received two shots by Sept. 19.

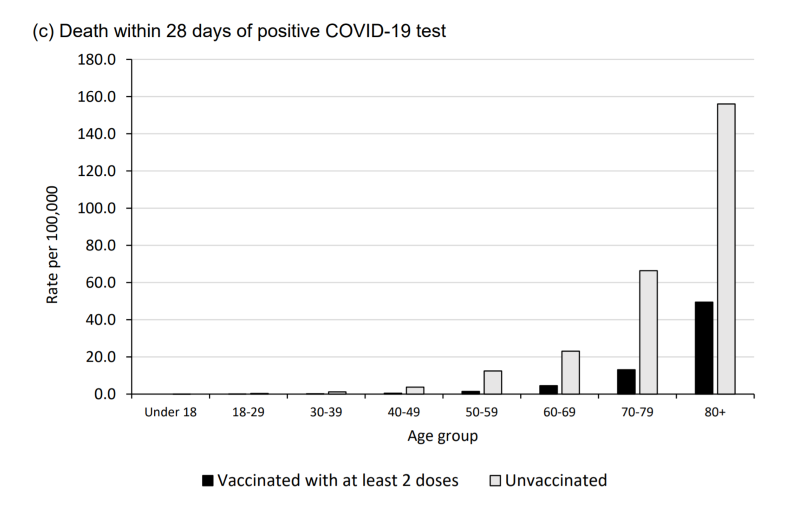

The same chart showing those death figures (see Table 4), shows the rates of death are higher among the unvaccinated than for the vaccinated. The death rate is calculated by comparing the number of deaths for vaccinated or unvaccinated people with the total population of each group.

The death rates for the unvaccinated are three to five times higher than the rates for the vaccinated among the 60-and-over age groups.

In the full three-hour podcast, Berenson acknowledges that the death rates indicate the vaccines provide protection, saying “what they’re showing you there is that even though the vast majority of people who died, were vaccinated, the vaccine still appears to have some protective effect.” But that acknowledgment is missing from the shorter clip circulating on Facebook; other social media and online posts misleadingly highlight the U.K. raw numbers of deaths, with some including similar data from other countries.

“As the number of people vaccinated in a population grows, we expect to see relatively more deaths in the vaccinated. This ‘base rate’ phenomenon can make it hard to interpret the data,” Natalie Dean, assistant professor in the Department of Biostatistics & Bioinformatics at the Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, told us via email. “It doesn’t mean the vaccines aren’t working well against deaths (they are) but just that the vast majority of vulnerable adults in the UK have been vaccinated.”

We’ve written about this issue twice before, including when social media posts misinterpreted figures on a COVID-19 outbreak in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

“Epidemiologists never look at raw number of cases if we want to think about anything causal, because they don’t tell us what we want to know. We need to know the denominator too,” Matthew Fox, professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Global Health at Boston University, told us via email. “Imagine if everyone in a population of 1 million people was vaccinated and there were 100 deaths. Every single one of them was vaccinated, but without a comparison population who were unvaccinated, we can’t say if the vaccine protected people because we don’t know how many people would have died if they all hadn’t been vaccinated.”

For a visual representation of this, see this blog post by Wake Forest University statistician Lucy D’Agostino McGowan.

Fox said the death rates for the vaccinated versus unvaccinated populations are the better measure, but even those are imperfect because of other factors in those groups. For instance, a greater proportion of the vaccinated group may be sicker individuals or those at greater risk of severe illness who had a strong motivation to get vaccinated.

The U.K. reports on these figures warn about misinterpretation, echoing what experts told us.

“In the context of very high vaccine coverage in the population, even with a highly effective vaccine, it is expected that a large proportion of cases, hospitalisations and deaths would occur in vaccinated individuals, simply because a larger proportion of the population are vaccinated than unvaccinated and no vaccine is 100% effective. This is especially true because vaccination has been prioritised in individuals who are more susceptible or more at risk of severe disease,” the week 38 report says.

The report includes estimates on vaccine effectiveness, which come from comparing rates among the vaccinated and unvaccinated and using community testing data, vaccination data, cohort studies and electronic health data. The observed effectiveness against symptomatic disease with the delta variant after two vaccine doses was about 65% to 70% with the AstraZeneca vaccine (which hasn’t been authorized in the United States) and 80% to 95% with the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines. “Vaccine effectiveness is generally slightly higher in younger compared to older age groups,” the report said.

Effectiveness against hospitalization and death was more than 90% for all three vaccines. “Relatively limited waning of protection against mortality is seen over a period of at least 5 months,” the U.K. report said.

Overall, the figures for the seven-day average of new deaths from COVID-19 in the U.K. are a fraction of what they were at the peak in late January, or even the high figures from April and May 2020, early in the pandemic. The seven-day rolling average was 1,248 deaths per day on Jan. 23, and it was 135 on Oct. 25, according to U.K. figures compiled by Our World in Data.

Rates of COVID-19 Cases

Our fact-checking colleagues across the pond at Full Fact wrote about another data point Berenson highlighted in that podcast, and which has been circulating to a lesser degree on social media: The U.K. report shows higher rates of confirmed COVID-19 cases for those in older age groups among the vaccinated compared with the unvaccinated.

The week 38 report showed those ages 40 and up who were vaccinated had higher rates of cases than the unvaccinated in the same age groups, while the week 43 report (for the four weeks ending Oct. 24) showed higher confirmed case rates for those 30 and older. Why would this be the case? For one, people have to get tested in order to have a confirmed case, so case numbers aren’t exact.

“The case rates in the vaccinated and unvaccinated populations are unadjusted crude rates that do not take into account underlying statistical biases in the data,” the U.K. week 43 report says. “There are likely to be systematic differences in who chooses to be tested and the COVID risk of people who are vaccinated.”

It goes on to say that fully vaccinated people may be more likely to get tested and more likely to have “social interactions because of their vaccination status,” leading to greater exposure to possible infection. Plus, COVID-19 infections among the unvaccinated in the prior four-week reporting period may be “artificially reducing” the case rate for that group in the latest report.

Full Fact also raised the issue of which official population figures are used for the total number of unvaccinated people. Since the unvaccinated make up a relatively small percentage of those in older age groups, even a small change in the estimate for the population of this group could throw off these rates.

Dean at Emory University raised the same point about the likelihood of getting tested. “People who are vaccinated may be more likely to seek routine testing or testing for mild symptoms. Their infections may be captured more often than infections in the unvaccinated,” she said. “This is more of a challenge for studying very mild disease. In contrast, severe disease is well-captured and not subject to these same biases.”

Also, Dean said there is “some waning of effectiveness against infection over time, so this may be more prominent” in the older age groups as opposed to the 18-29 age group who may have been vaccinated more recently. There has been “a drop off in effectiveness against all infections due to waning and the delta variant,” she said.

As we explained last month, multiple studies have found a reduction in real-world effectiveness against confirmed infections, though effectiveness against severe disease and death have remained robust. Those studies led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to recommend booster vaccine shots for some individuals.

Clarification, Nov. 3: We added the time frame to the chart source information.

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s COVID-19/Vaccination Project is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation. The goal of the project is to increase exposure to accurate information about COVID-19 and vaccines, while decreasing the impact of misinformation.