The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments Jan. 7 in two challenges to the Biden administration’s attempts to expand the use of vaccinations.

Here we present the facts on some of the COVID-19 claims made by the justices.

Children Hospitalized with COVID

In the first of two cases, the justices heard from lawyers who were seeking to block the Department of Labor’s temporary emergency rule for businesses with 100 or more workers that would require workers to be fully vaccinated or be tested at least once a week.

In her line of questioning during the case, National Federation of Independent Business v. Department of Labor, Justice Sonia Sotomayor vastly overstated the number of children with COVID-19 who are in “serious condition.”

In her line of questioning during the case, National Federation of Independent Business v. Department of Labor, Justice Sonia Sotomayor vastly overstated the number of children with COVID-19 who are in “serious condition.”

“We have hospitals that are almost at full capacity with people severely ill on ventilators,” she said. “We have over 100,000 children, which we’ve never had before, in — in serious condition and many on ventilators.”

According to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, there were about 4,700 children hospitalized in an in-patient pediatric facility on Jan. 10 who were “suspected or laboratory-confirmed-positive for COVID-19.” That includes those in “observation beds,” HHS noted.

There has been a concerning surge in children hospitalized with COVID-19 in recent weeks, particularly among the very young, though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that may be due to an overall surge in cases with the omicron variant rather than an indication of increased severity for young children.

“At this time, it appears that severe illness due to COVID-19 is uncommon among children,” the American Academy of Pediatrics wrote in a Jan. 4 report. “However, there is an urgent need to collect more data to assess the severity of illness related to new variants as well as the longer-term impacts of the pandemic on children, including ways the virus may harm the long-term physical health of infected children, as well as its emotional and mental health effects.”

Nonetheless, Sotomayor’s statistic on the number of children experiencing a “serious condition” as a result of COVID-19 was way off, assuming she was talking about hospitalizations, which the context of her comments suggests.

But Sotomayor was correct that cases of children hospitalized with COVID-19 are at a record high. So is the number of infections.

“COVID-19 cases among US children are increasing exponentially, far exceeding the peak of past waves of the pandemic,” the American Academy of Pediatrics reported, citing weekly data ending Jan. 6 that showed the cases nearly tripling over the course of two weeks.

According to the CDC, the seven-day average of hospital admissions for those up to 17 years old was 830 on Jan. 8. That’s a 34% increase from the week before. Of particular concern is the rise in the rate of cases among children ages 4 and younger who were admitted to hospitals and were infected with the coronavirus.

“Hospitalization rates have increased for people of all ages and while children still have the lowest rate of hospitalization of any group, pediatric hospitalizations are at the highest rate compared to any prior point in the pandemic,” Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the CDC’s director, said in a press conference on Jan. 7. “Sadly, we are seeing the rates of hospitalizations increasing for children zero to four, children who are not yet currently eligible for COVID-19 vaccination.

“We are still learning more about the severity of omicron in children, and whether these increases we are seeing in hospitalization reflect a greater burden of disease in the community or the lower rates of vaccination for these children under age 18,” Walensky continued. “Currently just over 50% of children, 12 to 17 are fully vaccinated, and only 16% of those 5 to 11 are fully vaccinated. We know that vaccination prevents severe disease and hospitalizations. … Please, for our youngest children, those who are not yet eligible for vaccination, it’s critically important that we surround them with people who are vaccinated to provide them protection.”

On “Fox News Sunday” on Jan. 9, Walensky was asked about Sotomayor’s comment, given that HHS was reporting only a fraction of the figure she cited for pediatric hospitalizations from COVID-19.

Walensky confirmed the lower figure was accurate and noted that “while pediatric hospitalizations are rising, there are still about 15-fold less than hospitalizations of our older age demographics.”

“Comparatively the risk of death is small, but, of course, you know, children aren’t supposed to die,” Walensky said.

COVID-19 Deaths

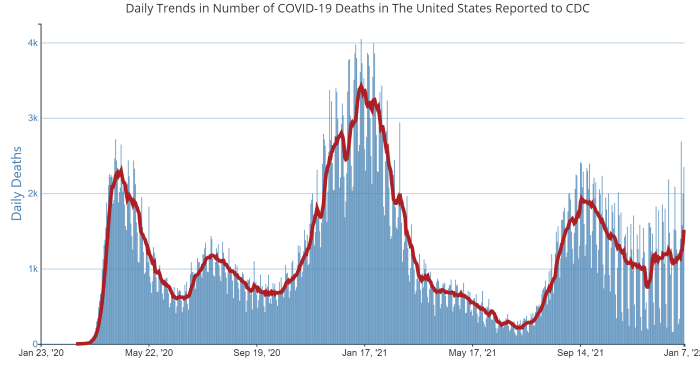

Sotomayor also said that “we are now having deaths at an unprecedented amount.” That’s incorrect. Daily deaths and the seven-day average of deaths due to COVID-19 reached their peak in January 2021.

On Jan. 13, 2021, the seven-day average of deaths was 3,421, and the number of deaths on that day was 4,048, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s the peak for the COVID-19 pandemic. As of Jan. 7, the day Sotomayor spoke, the seven-day average was 1,500 deaths, with the total reaching 2,230 that day. Since then, the seven-day average has risen slightly, to 1,552 on Jan. 9.

The latest figures are up a bit from December, when the seven-day average of deaths was around 1,100 to 1,200 for nearly all of the month. But the figures are not “unprecedented.”

Rising COVID-19 Cases

In the second case, Biden v. Missouri, the justices entertained a challenge to a Biden administration rule issued in November that requires eligible staff at health care facilities that participate in Medicare and Medicaid programs to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

At several points in oral arguments for both cases, Justice Stephen Breyer said there were about 750,000 new cases of COVID-19 yesterday. And, by one measure, he is correct.

“There were three-quarters of a million new cases yesterday. New cases. Nearly three-quarters, 700-and-some-odd thousand, okay?” Breyer said in NFIB v. Department of Labor. “That’s 10 times as many as when OSHA put this rule in.”

The CDC data show there were about 790,000 new daily cases on Jan. 6 — the day before the oral arguments. We prefer to use the rolling seven-day average of daily cases, which was nearly 615,000 on Jan. 6.

So, Breyer’s 750,000 figure was right by one measure. And, by that measure, he is not far off when he said it is “10 times as many as when OSHA put this rule in.” The Occupational Safety and Health Administration published the rule on Nov. 5, when there were 89,088 daily cases. The moving seven-day daily average was 71,454.

By either measure, Breyer’s larger point is spot on: The number of COVID-19 cases has been rising rapidly in recent months.

(We should note that Breyer mistakenly said “750 million new cases” at one point, drawing criticism from some conservative sites. But it was clearly a slip. He referenced the number 750,000 several times.)

Vaccine Effectiveness Against Coronavirus Transmission

On multiple occasions, while discussing the vaccine mandate for health care workers, Justice Elena Kagan alluded to the ability of the COVID-19 vaccines to prevent transmission of the coronavirus, or SARS-CoV-2, from health care workers to patients.

Although her comments were tied to the legal arguments, some of them could be interpreted to leave the false impression that vaccinated people cannot spread the virus.

“Well, all the secretary is doing here is to say to providers, you know what, like basically the one thing you can’t do is to kill your patients,” she said at one point, referring to HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra, who imposed the mandates in question. “So you have to get — you have to get vaccinated so that you’re not transmitting the disease that can kill elderly Medicare patients, that can kill sick Medicaid patients. I mean, that seems like a pretty basic infection prevention measure. You can’t be the carrier of disease.”

It has always been possible for a fully vaccinated person to spread the coronavirus, although vaccines reduce this risk, at least against the delta variant and other earlier versions of the virus.

Against omicron, it’s not yet known how well the vaccines prevent transmission. Several experts told us that the vaccines are expected to reduce some omicron transmission, but likely less than for delta.

“I think it is reasonable to suspect that there will be some level of protection — but difficult to say what this level is. And it could be small,” Johns Hopkins epidemiologist David Dowdy told us.

“The vaccine-mediated reduction in transmission for Omicron relative to Delta or prior variants is likely to be worse. Probably a lot worse,” Deepta Bhattacharya, an immunologist at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, told us in an email. “But that’s different than zero.”

“There is plenty of pre-omicron evidence that vaccines prevent transmission, including for delta. But what we know about omicron is preliminary,” University of Pennsylvania infectious disease fellow Dr. Aaron Richterman said.

The best evidence thus far, he said, comes from an unpublished study from Denmark that looked at infection spread in households. It found unvaccinated people were about 40% more likely to transmit than those who were fully vaccinated, who in turn were about 40% more likely to transmit than those who received a booster.

This suggests that vaccination can reduce transmission of omicron by lowering a person’s infectiousness, Richterman said. But the other main way that vaccination can reduce transmission — by preventing infection in the first place — may not apply with omicron.

“This is where we’re going to see a large drop [in transmission prevention] with omicron because two vaccine doses don’t really prevent infection,” he said. “Whereas with delta, you’re talking 70, 80% reductions in the risk of infection.”

Preventing viral transmission to patients, while important, isn’t the only reason why hospitals might want to make sure their staffers are vaccinated. The vaccines would prevent institutions from losing staff members for extended periods of time because of the reduced risk of severe disease and death, for example.