Q: Are electric cars really better for the environment than gasoline-powered cars over their lifetimes?

A: Yes. Electric vehicles typically release fewer greenhouse gas emissions than internal combustion engine vehicles during their life cycles, even after accounting for the increased energy required to make their batteries. And their carbon footprints are expected to get smaller in the near future.

FULL QUESTION

Hi. I have been sent this facebook post regarding Electric car battery information which does not seem factual to me but I would like to know for sure.

FULL ANSWER

After seeing various versions of a viral post on social media that plays up the environmental costs of electric vehicles, readers have been asking us if EVs are really better for the environment than conventional gasoline-powered cars. The post, which includes false and misleading claims, shares a photo of a Tesla car battery and is accompanied by a long caption highlighting the minerals and energy needed to manufacture the battery — ultimately claiming that EVs take a full seven years to begin lowering carbon emissions compared with a conventional car.

The production and use of all kinds of vehicles and fuels have environmental costs. Large amounts of raw minerals and other materials have to be extracted, manufactured and transported globally to make automobile bodies, engines, batteries and other components. Then the vehicles need to run — either on fuels such as gasoline or diesel, which also need to be extracted, refined, produced and distributed, or on electricity, which is generated from fossil fuels, nuclear power or renewables. And when vehicles no longer work, materials need to be recycled or disposed of. At each of these stages, vehicles are responsible for producing heat-trapping gases, known as greenhouse gases, that contribute to climate change. The total emissions across a vehicle’s lifetime are called life cycle or cradle-to-grave emissions.

The transportation sector had the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. in 2021, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Most of these emissions are carbon dioxide emissions that come from the combustion of fossil fuels in conventional gasoline or diesel vehicles. Light-duty trucks, such as SUVs, pickup trucks and minivans, were the largest contributors of the sector’s emissions (37%), while passenger cars accounted for 23%. These emissions will need to be nearly eliminated to achieve the ambitious climate target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, set by President Joe Biden’s administration.

Electric vehicles, or EVs, could play an important role in achieving that goal. Currently, making an EV is more carbon intensive, and expensive, than making a conventional car — largely because of the energy needed to make a battery. Yet studies show that even accounting for those emissions, over their entire life cycle, EVs contribute fewer greenhouse gas emissions than gasoline-powered cars. That’s because once they hit the road, the emissions associated with their operation are much lower relative to gasoline-powered cars.

“Electric vehicles are better for the environment. Full stop,” Austin Brown, director of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Vehicle Technologies Office, told us in a phone interview. “There are tons of complexity underneath that, but … in every metric that we use to measure environmental impact, that we know how to really quantify, electric vehicles are better for the environment now, and they will continue to improve.”

Jarod C. Kelly, principal energy system analyst at the DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, co-authored a 2023 study that analyzed cradle-to-grave greenhouse gas emissions and economic costs of electric and conventional cars. Kelly said the study found that under current conditions it would take an electric car 19,500 miles, or less than two years of typical driving in the U.S., to pay back the increased emissions of the manufacturing process and break even with a comparable gasoline car.

“After that, your electric vehicle is going to be reducing greenhouse gas emissions relative to a comparable conventional vehicle,” he told us in an interview. That payback time, he added, will get shorter as the electrical grid adds more renewable energy — Biden’s goal is to reach “100% carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035” — and the battery manufacturing process gets cleaner.

Even though EVs have no tailpipe emissions and don’t need to internally burn fuels to operate, they do need electricity, which is generated by a mix of fuels and energy sources. The emissions associated with driving an electric car, therefore, vary from region to region, depending on how carbon intensive the electricity mix is. For example, driving an electric car in California will result in lower emissions than driving the same car in West Virginia, since the latter is highly reliant on coal and uses fewer renewables to generate electricity. Other variables, such as size and model of the vehicle, driving patterns, and manufacturing location, can also make the comparison between EVs and conventional cars complex, Carbon Brief, a U.K.-based climate-focused website, has explained.

But in most scenarios, EVs win out with fewer carbon emissions. Similar to the DOE analysis, a 2021 white paper by the International Council on Clean Transportation, a research group that aims to improve transportation energy efficiency, found that the lifetime emissions of an average medium-size electric car were lower compared with a gasoline-powered car by “66%–69% in Europe, 60%–68% in the United States, 37%–45% in China, and 19%–34% in India.”

Misleading Viral Posts

Despite these analyses, thousands of social media users shared the post many readers sent to us, which incorrectly suggests there are few or no environmental benefits in owning an electric car. Similar claims — and others about EVs — have been debunked by some of our fact-checking colleagues.

“It takes SEVEN years for an electric car to reach net-zero CO2,” the post says. “The life expectancy of the batteries is 10 years (average). Only in the last three years do you begin to reduce your carbon footprint. Then the batteries have to be replaced and you lose all the gains you made in those three years.”

There are several inaccurate claims in those sentences.

To begin with, there are CO2 emissions associated with driving an EV.

“EVs are not zero-emitting vehicles. Hence, they never reach net-zero,” Sergey Paltsev, deputy director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, told us in an email after reviewing the post.

The post may have meant to claim that it takes “SEVEN years” for an EV to make up for the emissions required to manufacture it, when compared with the emissions of a conventional vehicle. But that’s false, too.

As we said, manufacturing an EV currently emits more CO2 than manufacturing a similar gasoline-powered vehicle. “Typically, EV manufacturing (including batteries) produces about 50% more emissions than manufacturing of the comparable ICE vehicles,” Paltsev said, referring to internal combustion engine vehicles and based on a 2019 study for which he was one of the lead investigators.

But, he added, “This increase is more than offset by lower emissions from fuel consumption by EVs.”

It takes between one and two years of typical driving for an EV to pay back its higher initial emissions, compared with a gasoline car, depending on where the EV battery is produced and where the car is charged. The payback time will go down as the electrical grid and the battery manufacturing process get cleaner in the future.

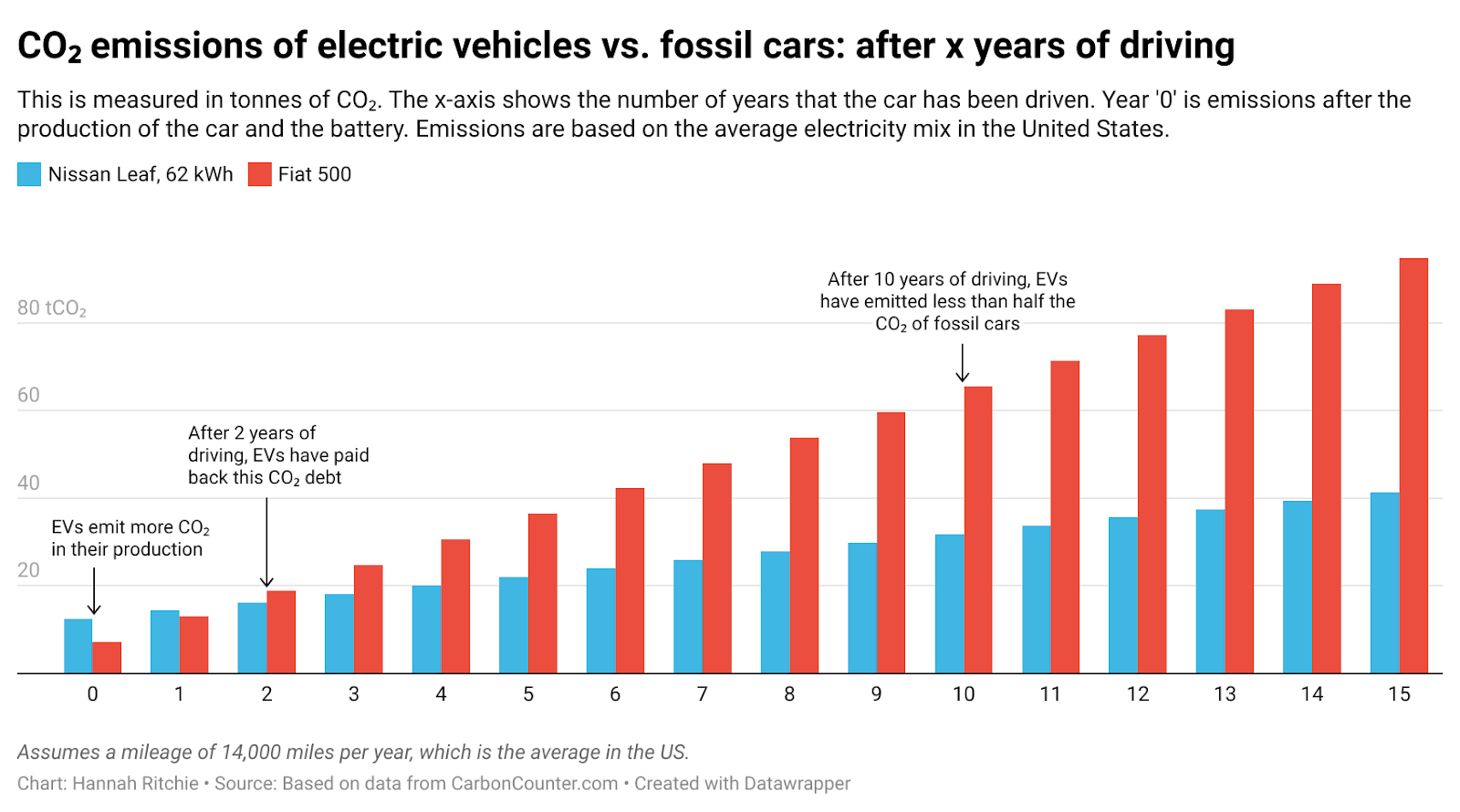

Hannah Ritchie, deputy editor and lead researcher at Our World in Data, estimated last year that, based on data from MIT’s CarbonCounter.com, “the average driver in the US could reduce emissions by half by switching to an EV.”

“As soon as you start driving, EVs start to pay back their carbon ‘debt’ quickly. In fact, after just two years of driving, EVs are already better. This gap grows year after year. After 10 years of driving, the Nissan Leaf would have half the emissions of the Fiat 500,” she wrote, after comparing cumulative emissions of two mid-range cars, one electric and the other powered by gasoline, for 15 years.

According to her calculations, “EVs emit much less than fossil cars” even if the battery was produced in a country with an electricity mix that is 100% coal — an extreme example that does not reflect reality. Currently, the majority of batteries are produced in China, which has an electric grid that is about 60% coal, she wrote.

Emissions associated with manufacturing EVs are expected to decrease in the future by moving parts of the production to the U.S., since the American grid is cleaner than China’s. Battery manufacturing capacity in the U.S. is expected to support the production of 10 million to 13 million electric vehicles each year by 2030, according to DOE.

While battery recycling is currently difficult, researchers have been developing new technologies to make it easier. In 2019, the Department of Energy launched a center to work on new lithium-ion battery recycling technologies, and car companies are also involved in this type of research. Improving recycling would not only reduce the cost of batteries, but also the emissions associated with making and disposing of them.

The post also claims that EV batteries last an “average” of 10 years, but that’s not exactly accurate. Currently, batteries are expected to last between 10 and 20 years. A DOE spokesperson told us electric cars being sold today are “designed to be consistent with conventional vehicle performance,” which is roughly a lifetime of 178,000 miles.

Most cars won’t need the battery replacement the post misleadingly claims they will. “We don’t expect most vehicles to need a new battery,” DOE’s Brown said.

Many EV manufacturers provide a warranty that the battery will retain 70% of its capacity for eight years or 100,000 miles, whichever comes first. That minimum warranty will soon be required in California, starting with 2026 model vehicles, and may become required nationally for 2027 EVs, if proposed EPA rules are finalized.

Minerals Required for EV Batteries

Other parts of the post focus on the mining required to make an EV battery. The post includes lists of the amount of minerals supposedly required to produce one Tesla Model Y battery; the machinery, fuel and labor needed to mine them; and the price of the batteries and the cars.

“Finally you get a ‘zero emissions’ car,” the post says, sarcastically.

It’s true that more minerals and mining are required to make an EV.

“Simply put, EV’s require more mining and processing,” Corby Anderson, director of the Kroll Institute for Extractive Metallurgy at the Colorado School of Mines, told us in an email.

According to the International Energy Agency, a typical electric car needs “six times the mineral inputs” of a gasoline car. A single electric car lithium-ion battery pack “could contain around 8 kg of lithium, 35 kg of nickel, 20 kg of manganese and 14 kg of cobalt,” according to Nature. These minerals are scarce, expensive and carry other environmental and sociopolitical costs.

For example, nearly 70% of the cobalt production comes from Congo, where “up to 40,000 children work in extremely dangerous conditions” in artisanal mines, according to the United Nations. In Chile, the country with the largest lithium reserve, environmental groups and communities living near the Atacama’s salt flats say the extraction from brine deposits, which requires large volumes of fresh water in a desert, alters the water supply and hurts critical flamingo populations, according to Reuters.

In the U.S., Biden’s goal is for half of new car sales to be electric by 2030. As we’ve written, emissions standards proposed by the EPA in 2023 are “projected to accelerate the transition” to EVs, which could mean 67% of new light-duty vehicle sales are electric by 2032. Experts expect the global demand for lithium batteries to grow more than fivefold in five years.

But the specific figures in the post on the mining needed to obtain the EV battery minerals — which are presented without pointing to any source — are difficult to interpret, experts said.

Kelly, from the DOE, told us it’s impossible to understand the numbers that are presented.

“This is really too vague to be able to fact-check what they mean by any of that,” he said. “The truth is we live in an industrial world,” he added, and most people are not fully aware that mining is required for almost anything we use, “so I think that there’s a little bit of shock value with some of these numbers.”

Anderson, who reviewed the values in the post sent by our readers, told us the numbers are a mixed bag in terms of their accuracy.

It’s worth noting that batteries may be produced with fewer minerals in the future. New designs of batteries already use less nickel and cobalt, and some are aiming to be cobalt- and/or nickel-free.

But more to the point, requiring “more rock to be mined” doesn’t mean that EVs are worse for the environment, David Manley, lead economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute, a nonprofit that works with several countries on managing natural resources and sustainable development, told us in an email. The post uses “false reasoning,” he said, because it ignores the environmental costs of fossil fuel extraction.

Drilling for oil, for example, can harm ecosystems, and oil spills can be environmentally damaging. As MIT’s Climate Portal explains, it’s difficult to directly compare the environmental harms that exist for both EVs and conventional vehicles — context that is missing from the post.

“This extraction and transport of fossil fuels has to be done constantly to fuel a [gas-powered] car, while the extraction of metals for an EV is done once,” he said.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.

Sources

“Alternative Fuels Data Center.” U.S. Department of Energy. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

Kelly, Jarod C., et al. “Cradle-to-Grave Lifecycle Analysis of U.S. Light-Duty Vehicle-Fuel Pathways: A Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Economic Assessment of Current (2020) and Future (2030-2035) Technologies.” Osti.gov. 1 Nov 2023.

“Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

“National Climate Task Force.” The White House. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

“Electric Vehicle Myths.” EPA. Accessed 25 Jan 2024.

Bieker, Georg. “A new life-cycle assessment of the greenhouse gas emissions of combustion engine and electric passenger cars in major markets.” The International Council on Clean Transportation. Jul 2021.

Brown, Austin. DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office director. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 19 Jan 2024.

Kelly, Jarod C. DOE’s Principal energy system analyst. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 19 Jan 2024.

Shaiq, Samah. DOE Press secretary. Email to FactCheck.org. 16 Jan 2024.

Nguyen, Andy. “CO2 output from making an electric car battery isn’t equal to driving a gasoline car for 8 years.” PolitiFact. 11 May 2021.

Baruah, Anuraag. “CO2 emitted in making an EV battery isn’t equal to driving a petrol car for 8 years.” Climate Fact Checks. 5 Sep 2022.

Petersen, Kate S. “CO2 emissions from gas cars outweigh electric, even with battery manufacturing | Fact check.” USA Today. 23 Jan 2024.

Paltsev, Sergey. Deputy director of MIT Joint Program on Science and Policy Global Change. Email sent to FactCheck.org. 22 Jan 2024.

Ritchie, Hannah. “Electric cars are better for the climate than petrol or diesel.” Sustainability by numbers. 26 Jan 2023.

Sisson, Patrick. “How does an EV battery actually work?” MIT Technology Review. 17 Feb 2023.

“California Vehicle and Emissions Warranty Periods.” California Air Resources Board. 13 Apr 2018.

Najman, Liz. “New Study: How Long Do Electric Car Batteries Last?” Recurrent. 27 Mar 2023.

Evans, Simon. “Factcheck: 21 misleading myths about electric vehicles.” CarbonBrief. 24 Oct 2023.

Hausfather, Zeke. “Factcheck: How electric vehicles help to tackle climate change.” Carbon Brief. 13 May 2019.

Anderson, Corby. Director of the Kroll Institute for Extractive Metallurgy at the Colorado School of Mines. Email to FactCheck.org. 18 Jan 2024.

“The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions.”International Energy Agency. May 2021.

Castelvecchi, Davide. “Electric cars and batteries: how will the world produce enough?” Nature. 17 Aug 2021.

Tabuchi, Hiroko, and Brad Plummer. “How Green Are Electric Vehicles?” New York Times. 23 Jun 2023.

Stone, Andy. “Raw Materials Pose ESG Challenge for EV Industry.” Kleinman Center for Energy Policy. 7 Jun 2022.

“Electric Future.” United Nations Climate Change. 23 May 2022.

Villegas, Alexander, and Ernest Scheyder. “Chile plans to nationalize its vast lithium industry.” Reuters. 21 Apr 2023.

Villegas, Alexander, and Cristian Rudolffi. “In Chile’s Atacama, lithium mining stirs fight over flamingos.” Reuters. 23 May 2022.

Villegas, Alexander. “How Chile’s progressive new plan to mine lithium faces Indigenous hurdles.” Reuters. 20 Jul 2023.

Steckelberg, Aaron, et al. “The underbelly of electric vehicles.” Washington Post. 27 Apr 2023.

Chang, Agnes, and Keith Bradsher. “Can the World Make an Electric Car Battery Without China?” New York Times. 16 May 2023.

“Insights into Future Mobility.” MIT Energy Initiative. Nov 2019.

McCrary, Eleanor. “Fact check: Viral image shows coal mining machine, not lithium mining.” USA Today. 6 Oct 2022.

Nguyen, Andy. “Instagram post misleads about lithium mining and Tesla cars.” PolitiFact. 13 Dec 2022.

“FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Private and Public Sector Investments for Affordable Electric Vehicles.” The White House. Press release. 17 Apr 2023.

Krisher, Tom. “The EPA’s ambitious plan to cut auto emissions to slow climate change runs into skepticism.” AP. 6 Aug 2023.

“Global demand for lithium batteries to leap five-fold by 2030- Li-Bridge.” Reuters. 15 Feb 2023

Manley, David. Lead economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute. Email to FactCheck.org. 16 Jan 2023.

“Reducing Reliance on Cobalt for Lithium-ion Batteries.” DOE. 6 Apr 2021.

McFarland, Matt. “The next holy grail for EVs: Batteries free of nickel and cobalt.” CNN. 1 Jun 2022.

Trafton, Anne. “Cobalt-free batteries could power cars of the future.” MIT News. 18 Jan 2024.

Lienert, Paul. “For EV batteries, lithium iron phosphate narrows the gap with nickel, cobalt.” Reuters. 23 Jun 2023.

“FOTW #1271, January 2, 2023: Electric Vehicle Battery Manufacturing Capacity in North America in 2030 is Projected to be Nearly 20 Times Greater than in 2021.” DOE. 2 Jan 2023.

“Biden-Harris Administration Announces $192 Million to Advance Battery Recycling Technology.” DOE. 12 Jun 2023.

Moseman, Andrew. “How well can electric vehicle batteries be recycled?” MIT Climate Portal. 5 Sep 2023.

Morse, Ian. “A Dead Battery Dilemma” Science. 20 May 2021.

Swanton, John. California Air Resources Board. Email sent to FactCheck.org. 5 Feb 2024.

Gore, D’Angelo, et al. “Trump’s Misleading Claims About Electric Vehicles and the Auto Industry.” FactCheck.org. 2 Oct 2023.

“Oil and petroleum products explained.” U.S. Energy Information Administration. 1 Aug 2022.

Ferreira, Fernanda. “How does the environmental impact of mining for clean energy metals compare to mining for coal, oil and gas?” MIT Climate Portal. 8 May 2023.

Ornes, Stephen. “How to recycle an EV battery.” PNAS. 26 Jan 2024.

McDermott-Murphy, Caitlin. “Coming Soon to a Grid Near You: Clean Energy (Batteries Not Included).” NREL. 15 Nov 2023.

Powell, Shayla R. EPA office of public affairs. Email to FactCheck.org. 6 Feb 2024.

Hawley, Dustin. “How Long Do Electric Car Batteries Last?” J.D. Power. 21 Sep 2022.

Kunz, Tona. “DOE launches its first lithium-ion battery recycling R&D center: ReCell.” DOE. Press release. 15 Feb 2019.

Jones, Nicola. “The new car batteries that could power the electric vehicle revolution.” Science. 7 Feb 2024.