Para leer en español, vea esta traducción de El Tiempo Latino.

In a Fox News interview, House Speaker Mike Johnson was spinning the facts when he claimed Republicans would have won a larger majority in the House in the 2024 election if not for Democrats’ gerrymandering of districts.

Johnson failed to mention that many states with Republican legislative majorities also gerrymander districts for partisan advantage. The net effect of redistricting did not give the Democrats a large advantage, experts told us, with most of them saying the Republicans benefited more than Democrats.

Redistricting is based on the decennial census, which counts the nation’s population every 10 years, as required by the Constitution. After the 2020 census, states with more than one congressional seat redrew some of their district lines to reflect population changes.

During a Dec. 4 interview on Fox News, Johnson blamed partisan redistricting for the Republican’s slim majority in the House, telling host Martha McCallum, “The House would have a larger majority, but redistricting and gerrymandering in the blue states made that almost impossible.” Republicans went into the 2024 election with a 221-214 majority in the House, but emerged with one fewer seat and a smaller 220-215 majority. (The GOP majority will be even smaller, at least temporarily, as Trump tapped three Republican members of Congress to join his administration and a fourth has resigned.)

We asked statisticians to gauge the effects of partisan redistricting on the 2024 congressional elections since the 2020 census. Depending on the methodology they used, these experts largely reached one of two conclusions — that Republicans derived a significant advantage from partisan redistricting, or that partisan gerrymandering had little net effect on the outcomes of the 2024 congressional elections, with either the Democrats or Republicans deriving a slight advantage. None of the experts we interviewed told us that gerrymandering provided Democrats with a large advantage.

As described by the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, each state redraws its electoral districts every decade to account for population changes determined by the census. While some states put independent commissions or courts in charge of the redistricting process, most states put the legislature in charge of drawing new electoral maps.

All About Redistricting, a site managed by University of Colorado Law Professor Doug Spencer, reported that legislatures in 39 states primarily control congressional redistricting, with most able to approve redistricted maps through a majority vote in each legislative chamber. Nine draw federal districts through independent commissions.

This redistricting process creates opportunities for gerrymandering, or the redrawing of electoral districts to favor a political party. The Campaign Legal Center describes that two primary tactics used in gerrymandering are “cracking” and “packing.” Cracking refers to splitting up a district possessing majority support for the opposing party into other districts, causing the opposing party to garner minority support from each newly drawn district. Conversely, packing refers to heavily concentrating the opposing party’s voters in a small number of districts such that it wins a few districts by very large margins instead of winning a larger number of districts by relatively smaller margins.

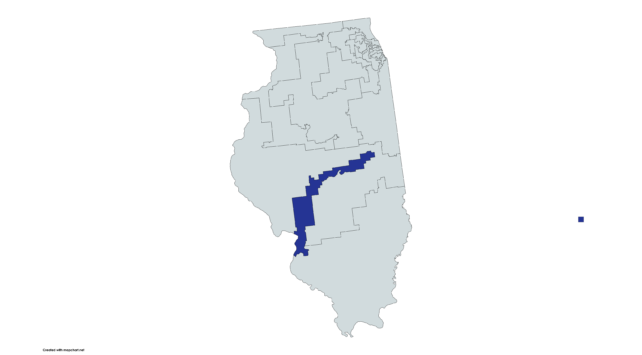

That’s how you end up with districts that look like Ohio’s 15th Congressional District, on the left, and Illinois’ 13th district, on the right, as illustrated below using MapChart:

Importantly, states also differ in the extent to which laws and other requirements prevent partisan legislators from seeking political advantage through redistricting. In June 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that “partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts,” leaving each state in charge of its own redistricting process. However, the court maintains that racial gerrymandering, or “redistricting in order to dilute minority voting power,” remains unconstitutional under the 15th Amendment.

As a result, Michael Li, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, told NPR in May 2023 that the extent of partisan gerrymandering varies considerably across the country. “In some states, you can get away with it. In some states, you can’t,” he described. This patchwork of differing restrictions on gerrymandering throughout the country creates an environment where both parties can carve out partisan electoral advantages in states where they control the redistricting process.

What Redistricting Experts Say

Each of the experts we spoke to agreed that both parties make efforts to gain partisan advantages from redistricting. However, when asked to quantify the extent to which gerrymandering altered electoral outcomes in 2024, we received diverging answers — though none agreed with Johnson’s claims that Democrats gained large seat advantages from redistricting.

David Niven, an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati who was once a speechwriter for former Democratic Gov. Ted Strickland of Ohio, strongly disagreed with Johnson’s claim, telling us in an email that “the Republican majority is entirely dependent on Republicans having gerrymandered far more seats in their own favor.” To quantify the effects of gerrymandering on the election, Niven compared each party’s congressional vote shares in a state to the party’s most recent presidential vote share.

“With presidential votes as a base, you can then simulate outcomes in each district by varying the lines and then tallying the results,” Niven said. “When maps drawn to be fair produce different partisan outcomes than the actual map, it is attributed to gerrymandering.”

While he agrees that both Democrats and Republicans engage in partisan redistricting, he concluded that Republicans’ gerrymandering efforts have been more frequent since the 2020 census. As a result, he argued that “Speaker Johnson’s comment is akin to Blackbeard saying he’d have more treasure if there weren’t so many thieving pirates out there.”

Employing a similar methodology, a report authored by Li, Peter Miller and Madison Buchholz from the Brennan Center found evidence of “extreme partisan bias … in 19 states: 11 where Republicans drew maps, 4 where Democrats drew maps, 2 where commissions drew maps, and 2 with court-drawn maps.” In particular, Li told us in an email response that “Texas and Florida have especially big skews” favoring the Republicans.

To explain this difference, the authors wrote, “This decade, as last, Republicans disproportionately controlled the redistricting process, drawing 191 (or 44 percent) of the districts that will be used in this year’s elections. By contrast, Democrats fully controlled the drawing of only 75 districts. The rest were drawn by commissions, courts, or divided governments.”

Overall, they found that these partisan maps generated 23 extra seats for Republicans compared to seven for Democrats — a net advantage of 16 seats for the Republican Party.

Importantly, Niven explains that the strategy he and the Brennan Center employ is “based largely on the premise that everyone behaves as a pure partisan” — that is, the baseline maps used to represent a hypothetically unbiased election result assume that everyone who votes for a Republican for president will also vote for a Republican in Congress. However, this assumption does not play out perfectly in the real world. For example, NBC News reported “that there are now more than a dozen Democrats in districts Trump carried, with just three Republicans in districts Vice President Kamala Harris won,” attributing the figures to Rep. Richard Hudson, chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee.

Jonathan Cervas, assistant teaching professor in political science at Carnegie Mellon who was a nonpartisan consultant on redistricting in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and New York, told us in an email that he agreed with Niven and the Brennan Center’s findings. While “the net effect of gerrymandering is difficult to gauge,” partisan redistricting “created a substantial advantage for Republicans nationwide,” making it “pretty clear that the Republicans have the advantage in terms of how the districts lines were drawn to favor a party,” he said.

Cervas, Nevin, and the Brennan Center’s report all pointed to North Carolina as an example of partisan gerrymandering affecting the 2024 election. In 2023, the state Supreme Court reversed an earlier ruling that had prevented the implementation of a Republican-drawn map in the 2022 election, with the court now concluding that they could not rule on cases concerning partisan redistricting. As a result, the Republican-controlled state legislature redistricted the state to favor their party. In what Cervas termed “textbook gerrymandering,” the Democrats lost three congressional seats in North Carolina between 2022 and 2024 under the newly drawn map, despite what he says were similar statewide Democratic vote shares in both elections.

However, Cervas also argued that the Republican advantage through gerrymandering has decreased in recent election cycles. The “Great Gerrymander of 2012,” as experts called it, created significant partisan advantages for Republicans in the aftermath of the 2010 census. But Cervas told us that shifting political control and interventions to courts and independent commissions have lessened the Republican Party’s advantage in recent election cycles. For example, Niven and Cervas both said that recent court rulings enforcing redistricting changes in Alabama and Louisiana favored Democrats over Republicans.

Alternatively, other experts used differing methodologies to quantify the effects of gerrymandering and found a smaller net effect from partisan redistricting.

In a 2023 study, Kosuke Imai, professor of government and statistics at Harvard University and the leader of the Algorithm-Assisted Redistricting Methodology Project, found — along with his team — that Republicans possess a net advantage of only two congressional seats from partisan gerrymandering.

Similar to Cervas, Imai told us in an email that partisan redistricting efforts largely favored Republicans over Democrats after the 2010 census. However, he said that “in the 2020 redistricting cycle, some states had a partisan bias toward Democrats. As a result, even though there was widespread gerrymandering in 2020, the partisan biases were mostly canceled out at the national level.”

In the 2023 study, Imai and his team identified gerrymandering by “comparing potential electoral outcomes under enacted district plans to those under a set of alternative plans that are created by simulation.” After sampling a series of nonpartisan simulated maps that abide by each state’s specific requirements, the team determined that “any differences in the partisan outcomes between the enacted plan and the simulated, nonpartisan baseline demonstrate the partisan effects of redistricting.”

Importantly, Imai told us that the two-seat Republican advantage calculated by his team “is not specific to the 2024 Congressional election. Rather, you can think of it as a general partisan bias of the enacted redistricting plan,” he explained.

Overall, Imai said that “about half of 2020 redistricting plans are biased in one way or another” in that they possessed “deviation from non-partisan plans that comply with redistricting rules.” However, because both parties engaged in partisan gerrymandering, he concluded that the Democrats and Republicans mostly canceled each other out.

Imai’s team summarized the results of their analysis in the figure below:

Lastly, the evaluation offered by Ellen Veomett, associate professor of computer science at the University of San Francisco, most closely aligns with Johnson’s claim that nationwide gerrymandering benefits Democrats. In a 2022 analysis published in the Washington Post, Veomett and her team concluded that Republicans were “at a slight disadvantage compared to where they could be” leading up to the 2022 midterm congressional elections. Describing the results of her study in an email response, she explained, “By our estimation, if you were to tally the additional seats that each party ‘unfairly’ were predicted to win [in 2022], Democrats had slightly more.”

Veomett and her team used the Geography and Election Outcome, or GEO, metric to evaluate the effects of gerrymandering on the 2022 midterm elections. As described in a paper published by Veomett and her team, the GEO metric incorporates both “election outcome data … [attempting] to measure the ‘packing and cracking’” and geographic “data about a map to identify irregularly shaped districts and flag them as potential gerrymanders.”

Veomett hasn’t yet updated her analysis to reflect districting changes since the 2022 midterms (such as the changes in North Carolina, Alabama, and Louisiana), inhibiting her ability to evaluate Johnson’s claim “with significant accuracy.” Asked to evaluate if the net effects of gerrymandering had shifted since 2022, she told us, “I’m guessing it’s similar for the 2024 election.”

When we asked Johnson’s office about his claim, his spokesperson referred us to a New York Post article published on Nov. 16. The article, which primarily cites GOP consultants, says that redistricting in states such as Illinois, New Jersey, Nevada and Michigan after the 2020 census created electoral advantages for Democrats. In the story, reporter Jon Levine wrote that “ultra-gerrymandered districts around the country have made it close to impossible for Republicans to make even bigger gains in the House.”

Johnson’s office also pointed us to New York, where they argue that recent redistricting made at least three districts in the state “safer for Democrat incumbents.” Because of these changes, Johnson’s office argued that “the overall impacts of redistricting and gerrymandering since the 2020 census … have contributed to Democrat wins and cut down the size of potential Republican House victories.”

Many of the expert analyses we cite above, including the studies conducted by the Brennan Center and Imai’s team, agree that some of these states (particularly Illinois) did engage in partisan gerrymandering that favored Democrats. Similarly, Dave Wasserman, senior editor and elections analyst at the Cook Political Report, told NBC News in February that New York’s redistricting changes did constitute “a mild gerrymander” that favored Democrats.

However, singling out gerrymandering by Democrats, as Johnson did, considers only one side of the equation. Both parties engage in partisan redistricting, and on aggregate, experts said that these nationwide gerrymandering efforts either significantly advantage Republicans or have little overall effect — making it dubious to claim that gerrymandering made a larger Republican victory “impossible.”

The divergence in findings between the experts we spoke to underscores that precisely quantifying the effects of gerrymandering on a specific election is far from straightforward. However, Johnson’s remarks blaming Democrats for biasing election results through gerrymandering, without recognizing his own party’s efforts to shape elections through partisan redistricting, amounts to misleading political spin.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.